By Gin Kai

Ubalbo C. Arizmendi is grateful to have seen the world, but regrets having seen it at a time when it was trying to destroy itself.

Born in the South Texas town of Brownsville, Arizmendi was 8 when his mother died. Although he knew his father, an aunt served as caretaker for him and two brothers.

With an absent father, he was forced to grow up quickly. At 10, he learned to be a mechanic by working at a garage across the street from his house.

"Our lives were very poor," he said. "We didn't have any luxuries."

Arizmendi decided to go into military service at the age of 17, but didn’t tell anyone in his family. He made his father unwittingly sign his consent forms and was able to enlist in the U.S. Army. On Nov. 7, 1941, he headed for Camp Roberts, Calif., for basic training.

During a break a month later, Arizmendi and his friends took a bus into town and were met by members of the military police upon their arrival. The MPs alerted them to the attack on Pearl Harbor and sent everyone back to base.

The United States was at war.

"We were issued rifles with live ammunition -- everybody was loaded. We were so close to the water they expected someone would try to harm us," said Arizmendi, referring to his base's West Coast location.

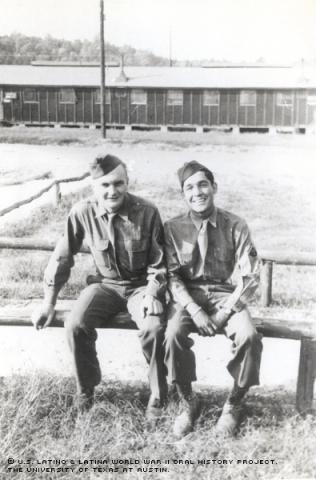

Soon, he was sent to the Alaskan islands, where his unit, the 30th Field Artillery Group, distributed machine guns and ammunition to troops on the front lines. After about two months, he was ordered to Blackstone, Va., to receive training on how to handle machine guns and engage in anti-aircraft fighting.

Then, he and other members of the 30th field artillery group headed with additional troops for England on The Queen Elizabeth. On the second day of their Atlantic voyage, they were instructed to put on life preservers because German submarines were waiting in the waters. The Germans fired several torpedoes, but the ship was too fast and maneuverable and evaded the enemy fire.

"It was a monster that could turn on a dime," said Arizmendi of the ship.

On June 6, 1944, Allied forces landed at Normandy. Now on another ship, Arizmendi was aboard one of the many lined-up trucks waiting to be dropped off on hostile ground. A chaplain and his driver were in the Jeep in front of his, and he watched helplessly as the vehicle disappeared into the water as it left the ramp. But he was ordered to move forward and, after crossing over the submerged Jeep, wondered about the fate of its passengers. Three weeks later, he was happy to see them alive. The chaplain and driver had been able to swim back to the safety of the ship.

"It was amazing to me. I thought I had smashed them," he said.

When Arizmendi arrived in France, he started working as an airplane mechanic as part of the Field Artillery Division, working primarily on small aircraft used to spot enemy targets. He also had to be on the lookout for enemy planes and be prepared to shoot them down.

As a lookout, Arizmendi would be on guard for up to three days without any sleep. As he lay in bed one night, he awoke from the sound of a voice speaking in German, and his first instinct was to reach for the .45-caliber pistol he kept under his pillow. Fortunately, a German-speaking Russian soldier assigned to the unit explained he wasn’t an enemy soldier, but a turncoat detailing the location of enemy soldiers who’d just passed by his house. That very day, Arizmendi's unit captured seven Germans.

As Arizmendi's unit advanced into Germany, they fought in small towns along the way. It was his job to scout for a vacant house for the men in which to sleep. On the wall of one of the homes, was a framed picture of Hitler concealing a safe. Arizmendi cracked the safe open by shooting a couple of rounds from his gun and found it filled with German money. The day was so cold and miserable that they used what they thought was outdated money to build a fire. He found out later the currency was legal tender that could have been used for purchases after the war.

"We must have burned millions of dollars," he said.

Later, Arizmendi's outfit went on to liberate survivors of a German concentration camp. The camp turned out to be the infamous Dachau.

Upon entering the camp, the Americans had to tape up their pants and put grease all over their body to avoid the infestation of lice and other bugs. Once inside, they found hundreds of gaunt prisoners, their bone structure visible beneath their skin.

"It was the most horrible place you can ever think of," Arizmendi said. "It stunk so bad you could smell it for miles."

His unit reached a small town late in the evening, where they encountered a group of imprisoned young girls locked up in chicken coops that were a mere 3 feet in height and 6 feet in length. The American soldiers made the girls' captors open every cage, and burned the small, makeshift prisons after the girls' release.

As they neared Berlin, German people joined hands to form a human chain across in an attempt to prevent American trucks and tanks from entering their city. Worse, snipers would shoot wounded GIs on their way back from the front.

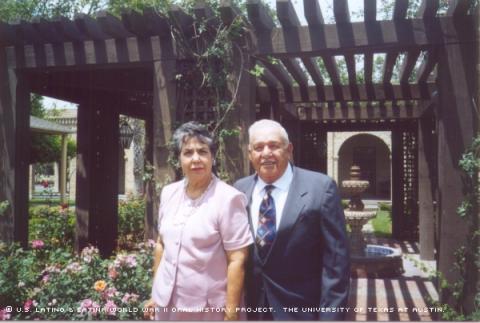

Arizmendi was discharged Nov. 18, 1945, and married Guadalupe "Lupita" Coronado six years later. Wedded 51 years, the pair has five grown children -- two daughters and three sons -- and lives in Brownsville.

After seeing so much suffering -- death and starvation especially -- Arizmendi takes nothing for granted. He said the experience permanently changed his life after the war.

"I was happy being able to work and feed myself instead of someone giving me food," he said. "That makes a difference in the mind to anybody that has been through what we gone through."

Mr. Arizmendi was interviewed in McAllen, Texas, on April 6, 2002, by Andrea Shearer.