By Justin Lefkowski

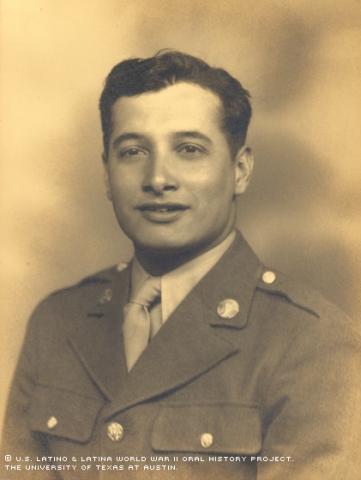

Salomon Abrego was at the Battle of the Bulge, where he and his fellow soldiers suffered through one of the coldest winters to hit the area in more than 20 years.

As a medic, Abrego watched helplessly as the cold ruined some supplies.

"It was so cold that the plasma was freezing," he said. "Soldiers were going into shock because we couldn't use it."

Abrego, who earned the rank of Private First Class, was personally touched by the deaths he saw.

"My friends were dying around me. It was pretty sad," he said. "It was depressing at night, when you had a chance to feel that way."

Abrego, a native of Laredo, was only 20 years old during the Battle of the Bulge.

He’d also be among the troops who liberated prisoners from concentration camps, including Buchenwald.

Tragedy stuck him and his family when his older brother was killed in an airplane crash on Tinian Island, part of the Mariana Islands group, in the Pacific.

By the time the private returned home and resumed his life, he’d lost something else to the war: his innocence.

Abrego was born Feb. 24, 1923. As a child growing up in Laredo, he says he indirectly faced discrimination in school.

"I just thought that was the way it is: white men getting the best jobs," he said.

His biggest problem, he said, was that he spoke only Spanish.

"I didn't understand what the teacher was saying," Abrego said.

His confusion didn’t last long. He ended up learning English by the time that he was 8 and graduated from Martin High School in Laredo in 1942.

Abrego says he’d always wanted to join the Army, even when he was a little boy.

"I enlisted into the Army for three reasons: It fascinated me, there was food and because they were going to get me anyway," he said.

Abrego's older brother, Guillermo, enlisted in the Army Air Force a few weeks after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor. Abrego enlisted in 1942, going first to Fort Sam Houston near San Antonio, then overseas by ship. The Aquatania took 10 days to get from New York to Scotland, and he had a terrible bout with seasickness.

"I got so seasick that I wanted to die. I lost 10 pounds. I couldn't hold any food or water," said Abrego, who noted more than 14,000 men were on the ship with him.

After arriving in Scotland, Abrego was sent to London. He reached his destination at 4 a.m., and the conditions weren’t good.

"We got there during an air raid, and they wouldn't let us leave until it was over," he said. "It wasn't too bad. It only lasted for about an hour."

Abrego had his sights set on joining the infantry and heading to the front line. But his superior officers had other plans: He was assigned to be a medic.

"They saw where I excelled. I knew about biology. I wanted to be a surgical technician," he said.

Abrego was sent to help liberate concentration camps, with the job of cleaning and feeding the victims they were able to save.

"The worst thing that I saw there was a young mother with babies and children fight for the food that was thrown away," he said.

At the time, DDT insecticide powder, then thought to be harmless to humans, was used to clean lice off the victims.

"At the end of the day we would all be white like someone had thrown a sack of flour on us," he said.

During more difficult times, Abrego and his comrades survived on K-rations, hard chocolate and small cheese sandwiches. When times were good, Abrego was lucky enough to have a kitchen to work with. They would give the men powdered eggs, powdered milk and margarine.

"The eggs were pretty good, the milk was not so good," he said. "The margarine was pretty good 'cause it tastes and smelled like butter."

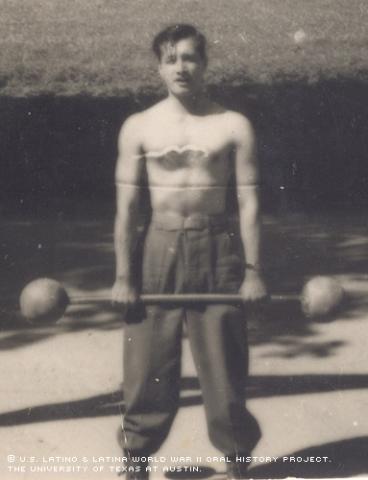

Abrego mentions the innovations caused by the war: Margarine, for instance, became more popular, particularly because it didn’t require refrigeration. Also, he points to the multi-colored shirt he’s wearing and says nylon was developed as a substitute for silk, which was needed for parachutes during the war.

But the war also took away Abrego's older brother. Guillermo Abrego died in July of 1945 while trying to safely land a B-24 Liberator after all the other passengers had parachuted out. There were three landing strips to choose from, but with no lights available to guide him, Guillermo tried to land the plane on a strip that was under construction. The plane crashed, and he died from severe head injuries three hours later.

Abrego says he isn’t a church-going person, but he does believe in God.

"I've never been to church. It's like a fairy tale," he said.

He then laughs and says that when he was in danger during the war, he thought about a God.

"I think about God, but I don't believe in organized religion. I don't like the rituals. You pray to God, you can pray anywhere. You don't need to go to church."

Abrego was discharged from the Army in December of 1945. He came home to the open arms of his mother, who was the only one there to greet him.

He went back to school at the University of Texas at Austin and earned a pharmacy degree. He became a pharmacist in Laredo, where he still works today, and married Evelyn Newell on July 10, 1948. The couple has four children, all of whom are involved in the medical field.

Abrego says his life after the war has been blessed by his family: four children, six grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.

Having led a life that some would envy and few have ever experienced, Abrego says he has no regrets.

Mr. Abrego was interviewed in Laredo, Texas, on September 28, 2002, by Juan de la Cruz.