By Mosettee Lorenz

By the time he was 22, Kansas native Ricardo León Martinez had dropped out of high school, gotten married and had four children, and he was at risk of going to prison for fighting and drinking.

But when he headed for Vietnam in the mid-1960s, he found a new perspective. In the years after the war, Martinez returned to school, got a college education and worked for the federal government for 34 years.

Martinez’s father, Ignacio, was recruited to work on the Santa Fe Railroad in Newton, Kan., sometime in the 1930s. He was later joined by his wife, María Neri Martinez. The couple went on to have 13 children, five girls and eight boys. Seven would serve in the military.

In 1963, Martinez dropped out of Newton High School his junior year and later married a classmate.

Martinez worked as a hotel bellhop to support his family. He drank in bars and fought the other customers, which got him in trouble with the police.

“I really needed to get out of here or else I might end up in prison someplace,” Martinez remembered thinking at the time, so in 1965 he enlisted in the Army.

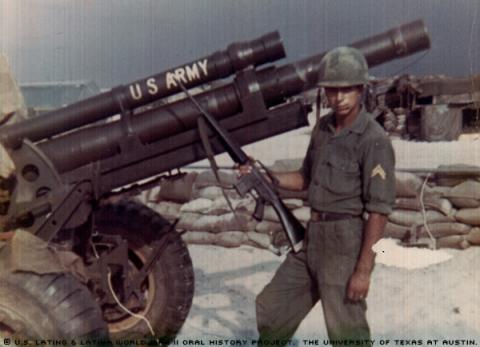

He completed his basic training at Fort Hood in Texas. Martinez said soldiers from Fort Hood occasionally went to bars in Waco, but he never did because he heard the people were racist. The second part of his training was completed at Fort Bragg in North Carolina, where he specialized in artillery.

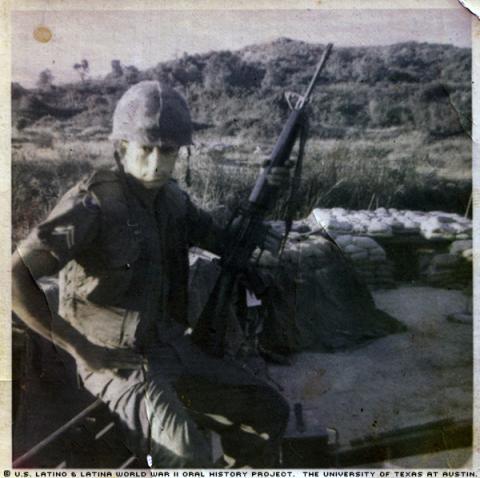

After finishing his training, Martinez volunteered to go to Vietnam. He was sent to Fort Riley in Kansas to train with the 9th Division. “We were training to get deployed,” said Martinez.

In 1966, he was deployed to Vietnam, leaving his wife and four children with her parents in Newton.

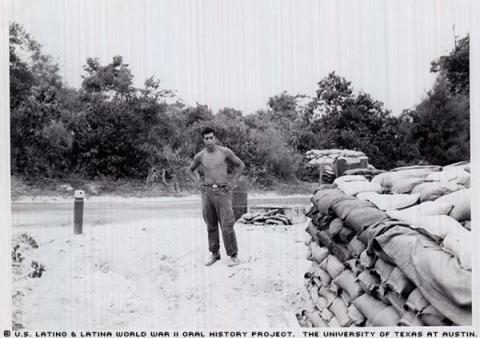

Martinez and the 9th Division began their tour in the Mekong Delta, about 20 miles northeast of Saigon. He later transferred to the 196th Light Infantry Brigade and was stationed in Tay Ninh Province and Chu Lai. In September 1967, the 196th Brigade joined other brigades to form Task Force Oregon, which became known collectively as the 23rd Infantry Division, or the Americal Division.

He was center gun, which means, he added later, that “we fired most of the fire missions. In an artillery battery there are [six] gun positions … we were the [third] gun position.”

After Operation Benton, Martinez was promoted to sergeant because of his artillery skills. Martinez recalled that his responsibilities changed when he was promoted.

“I had to make sure these guys were taking their malaria pills,” said Martinez, “I had to be their mother and father all at once.”

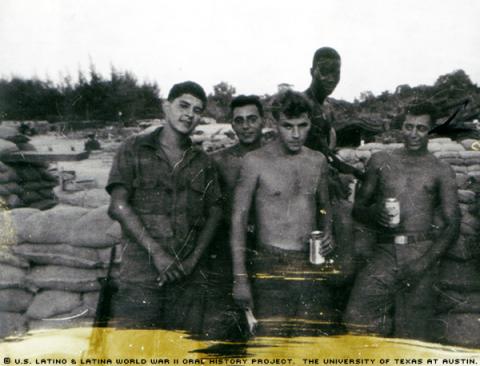

Initially, the 196th Brigade was entirely an African American unit. The brigade’s racial makeup changed as men returned home and were replaced by other soldiers.

Martinez noticed that African Americans and the Latinos socialized together, and not so much with Anglos.

Back in the U.S., protestors marched for civil rights and against the war. “We were over here fighting for this country, our country … and people just didn’t appreciate it,” said Martinez. “But then again maybe it was the protestors who brought the men home from the war.”

Martinez returned to Newton from Vietnam in November 1967. He was part of Battery A, 3rd Battalion, 82nd Artillery, 196th Light Infantry Brigade.

He noticed the homecoming of the Vietnam vets was different from those coming home after World War II. “(WWII) veterans had parades and had all kinds of nice celebrations, whereas Vietnam vets came home by themselves, not with their units,” said Martinez. “We weren’t given parades and celebrations. … They pretty much thought we were losers.”

Although no one said the word “losers,” Martinez said it was obvious by how Vietnam veterans were not asked to join veteran groups until the organizations started losing members.

Martinez is a member of Vietnam Veterans of America, the American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars.

Although he returned uninjured, Martinez carried invisible scars from the war, and he struggled with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Every time he hears a helicopter he looks up. Every July 4 the sound of fireworks creates flashback memories of firefights in Vietnam. “I just wanted to be alone, to be left alone,” said Martinez about the effects of PTSD. “There was so much to think about.”

As a result, he began to distance himself from his family. In 1970, Martinez said he saw no future in Newton so he divorced his wife and left again.

With only $20 in his pocket, Martinez moved to Kansas City, Mo., about 180 miles northeast of Newton. “I was employed for about [six] months when I was laid off,” he wrote later. “I couldn’t pay the rent and so I became homeless. I lived in a park and then later a friend took me into his place.”

He eventually found a steady job at Western Missouri Mental Health Center.

“[I]t is unfortunate that there are many vets homeless … it’s a tragedy,” he added.

While he was working, Martinez used the G.I. Bill to attend Penn Valley Community College at night. He earned an associate degree in administration in criminal justice, which enabled him to work with the federal government for 34 years. “I worked for [the] Department of Labor, Office of Federal Contract and Compliance and for the Veterans Employment and Training Service. …” he wrote later.

Martinez went through two more divorces before he married Mary Francis Callahan, who has been his wife for more than 20 years. He added that he thinks PTSD helped destroy his previous marriages. Why did the last one work? Martinez said simply, “My present wife is very understanding and caring.”

Martinez went a step further to recover from the war by attending church services. He went to afternoon Mass every day at the St. Patrick’s Catholic Church in Kansas City. The church, he said, needed ministers, and the priest asked him to be a lector. “[W]e helped with giving communion,” he explained, “and I also read scripture.” He also lectored at the cathedral downtown. Martinez had been an altar boy. “I was always a religious person,” he recalled.

Martinez said embracing his faith helped him have a positive attitude about life again. “The power of prayer is good, and it did help me,” said Martinez.

(Mr. Martinez was interviewed at Donnelly College in Kansas City, Kan., on June 17, 2010, by Maggie Rivas-Rodriguez.)