By Brian Villalobos

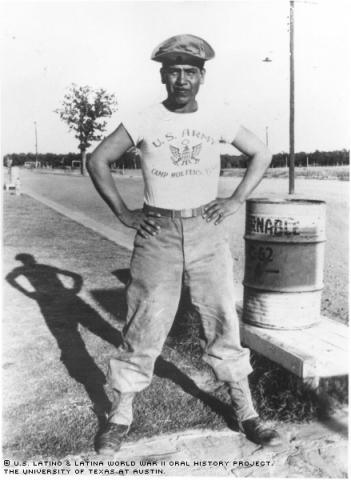

Raul Martinez's hands, thick, square and accented by a crest of jagged, walnut-sized knuckles, don’t seem to match his large, soft eyes.

Over the past 76 years, these hands have handled everything from cement to machine guns to mortar charges.

Martinez was born and raised in Cementville, Texas, a small cement company village north of Alamo Heights in San Antonio. One of 10 children born to Teofilo and Manuelita Martinez, both Mexican natives, he soon got a job at the same local cement factory where his father and grandfather had both worked.

By 1943, however, Hitler's German army was losing ground, Allied forces struck decisive blows at Stalingrad and Leningrad and 18-year-old Martinez found himself drafted and stationed on the front lines of the Second World War.

"We were scared . . .” he said. "We'd never seen anyone shoot someone else with real bullets."

Martinez's wartime experience was nonetheless not without moments of levity. He recalls a particular occasion on which he and a friend, hungry and stationed in Casablanca, decided to buy dried meat from street vendors, but realized after eating part of it, they weren't quite sure what kind of animal they’d purchased.

"I asked, 'What kind of meat is that?' [The vendor] says, 'guau-guau -- dog meat,'" Martinez said.

"We said, 'Well, now it's too late.' So we started to eat it. We already had some in our stomach[s.]," he said. "It tasted good. We were hungry."

More often, however, Martinez was surrounded by the sobering sense of reality evident in a piece of advice he said he received from his sergeant early on: "If you want to get home, you'd better shoot.”

"I learned to shoot from the hip, running, without aiming at nothing," Martinez said. "You get to be an expert."

This claim is corroborated by the assortment of medals he earned during the war, among them, two Expert Rifleman pins, a Sharpshooter medal and the Silver Star, awarded to Martinez, "For gallantry in action, for fearless operation of a machine-gun in the face of fire that inflicted seven casualties among his comrades."

Asked to speak more specifically about the "gallantry" alluded to on his award certificate, he said quietly, "I don't like to brag about it."

Martinez's decorations also include two bronze stars and French and German medals; he rose to the rank of Master Sergeant before his honorable discharge.

Martinez was a machine-gun specialist in the Company F, 7th Infantry, 3rd Infantry Division, when, in an area vulnerable to enemy attack, his captain ordered him to arrange weapons to create a crossfire. Martinez said he was behind the captain when a sniper shot him in the foot. A medic managed to pull the young soldier through the snow and out of the line of fire.

"I said, 'what happened . . . how's the captain?'" Martinez recalled.

"[The medic] says, 'No, he didn't make it . . . I'm going to give you morphine.'

“[He gave] me a shot -- it was cold -- and [then he] put me in the basement. And I heard a tank coming up there, and they [killed] the sniper. And then [the medic] says to me, 'You're going to be surprised -- it's a woman sniper."

Martinez remained on the front lines in Austria until the war's end in 1945. He said that when word came that a ceasefire had been declared and the conflict was over, he didn’t celebrate.

"Nothing like that, no. Some of the guys did, but not this Mexican here. I was still scared," he said.

He was offered 90 days furlough and higher rank if he would stay longer to secure the victory, he said, but he opted to return to San Antonio, where he married and resumed work at the cement plant. He worked there for another 40 years.

After the war, it took him awhile to shake off the ghosts of combat. Three months after coming home, he recalls driving along when his 1934 Chevrolet car had a blowout.

"I remember coming to a church," said Martinez, "me and my wife. I had the uniform on, and we had a [blowout] in that old car . . . I got out shaking. For a couple of years, you still shake. Sometimes you still shake. I do . . . Sometimes I have dreams."

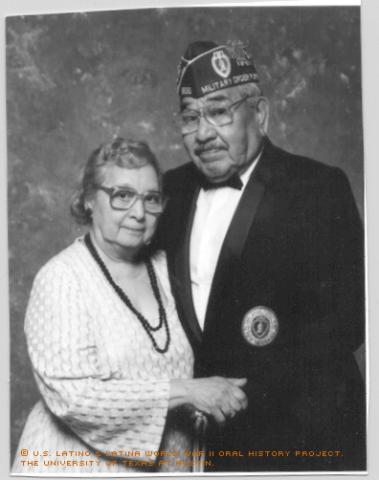

Martinez’s wife, Beatrice Bustos Martinez, said she supports her husband and is proud of his service record.

"I just wish he could tell you [more,]" she said. "I should get all of this down ... I've been making the book for him to leave for the children . . . I've got to write the story."

Martinez and Beatrice married on Nov. 18, 1945. The couple has four children: Raul, Dianne, Elaine and Audrey; they also have eight grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

Even after 58 years of marriage, he and Beatrice are still newlyweds, "in our heads," Martinez said.

Mr. Martinez was interviewed in San Antonio, Texas, on October 13, 2001, by Robert Mayer.