By Sara Kunz

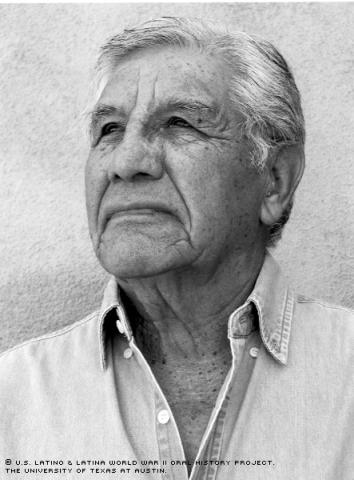

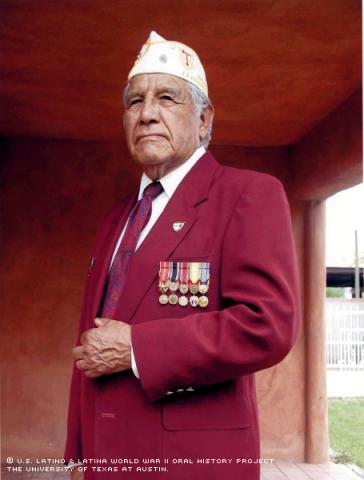

Ralph Rodriguez dreamed of being an ambassador to Central America after graduating from college, but his plans were crushed when he was drafted into the U.S. Army in February of 1941. Rodriguez had been working at New Mexico Timber Co. for three years when he was called to war.

Because his mother was traveling from Mexico to El Paso, Texas, when Rodriguez was born, he didn’t receive a birth certificate until his baptism in Juarez, Mexico. In correspondence after his interview, he explained how upon arrival in El Paso, a "kind lady" offered his mother, in the throes of pregnancy-induced pain and discomfort, lodging for the night. Rodriguez was born that night, on Oct. 25, 1917. He was later taken to nearby Juarez, Mexico, to be baptized.

The Rodriguez family moved to New Mexico when his father became a lumber inspector there. Rodriguez spent his formative years in the state, developing an interest in world politics and history in the process. He remembers the airwaves being filled during his adolescence with the demagoguery of Adolf Hitler.

"I stuck to the short-wave radio, listening in the night, hearing Hitler talk until two or three o'clock in the morning," Rodriguez said. "I didn't know what he was saying, but I just wanted to hear him talk."

After graduating from a Catholic high school in 1937, Rodriguez began working at the timber company while attempting to enroll in college. But his academic plans were halted when he was called up.

Rodriguez was drafted as a private in the 200th Coast Artillery Regiment (Anti-Aircraft) of the New Mexico Coast Guard in February of 1941. He started translating the Articles of War to Latinos, given his fluency in English and Spanish. Soon, he applied to transfer to the medical corps. The Army was reluctant to give him the transfer because of his invaluable translation skills, but ultimately Rodriguez was transferred as a caretaker for the sick and wounded.

Describing his initial days there as an "easy life" -- watching movies, working on the islands among bountiful flora and fauna and admiring incredible sunsets -- Rodriguez recalls that paradise was short-lived. By early December, Japanese aircraft began spying on the American soldiers stationed there, prompting U.S. fighter planes to take to the skies to investigate. The enemy planes dispersed, but Pearl Harbor was attacked shortly afterward in Hawaii. Rodriguez and his fellow soldiers feared they'd be the next target.

That afternoon, he looked up in the sky and counted more than 60 Japanese bomber planes flying in a V-shaped formation toward the American camp.

"We had just eaten and lay down in the barracks when the bombs dropped at 12:27," he said.

The American planes that had been patrolling the skies were no longer airborne during the onslaught, as their pilots had landed for lunch.

The vulnerable U.S. forces scrambled for their guns and fired into the sky. A fellow soldier grabbed Rodriguez and told him to help by guiding an ammunition belt, but the 37-mm projectiles on the 50-caliber machine gun only reached 17,000 feet -- far short of the 30,000-foot altitude level of the Japanese aircraft. Rodriguez survived the attack unscathed, and headed for the hospital to care for the wounded and bury the dead.

"It's amazing how you survive," Rodriguez said. "Sometimes you survive by knowing exactly what to do and how to counteract whatever is happening; other times you just act normal and try to escape from one place to another."

During a break in the fighting, he was sent to Manila with a medical detachment. Within a few weeks, all of the soldiers were sent to the Bataan Peninsula, including Rodriguez.

The soldiers spent their days in Bataan evading bombers. Often, GIs would spot "Photo Joe," the sobriquet given to a small Japanese plane that would fly above the American camps to take pictures before the bombers' arrival. Photo Joe's presence gave an early warning before bombings.

Sometime between February and March of 1942, Rodriguez contracted malaria and was sent to headquarters to receive treatment. He was in desperate need of nutrition in the wake of severe weight loss. After returning to the front lines, he fell ill again.

Amid the distress, Rodriguez asked a cleric what their likely fate would be. The priest's premonitions of surrender haunt him to this day.

"I hated myself for asking him," Rodriguez said. "I even hated the priest for a second or two."

Soon after, soldiers tied a white flag to a bamboo stick. Rodriguez assisted with the burning of the American flags, leaving lingering bitterness even now. The soldiers then walked by rank to surrender.

The next afternoon, the Japanese ordered the American GIs to begin marching. Soldiers who faltered during the march were prodded with bayonets, while those unable to continue were killed.

He remembers a sense of brotherhood among the Latino soldiers who’d march together in groups, and assist each other along the way.

When the soldiers reached their detention center, they were put in a 30-by-100-foot fenced area. Later, they were forced into boxcars. One hundred soldiers were crammed into a car that was built to hold 40 or 50 men. The train took the soldiers on a four-hour ride to Camp O'Donnell, where Rodriguez became a prisoner of war.

"I think the Japanese were afraid of us even though we were in prison camp," Rodriguez said. "I got a feeling that they weren't sure they had conquered us."

Their captors routinely beat them. Occasionally, the prisoners would entertain themselves by singing. Rodriguez found a Bible with missing pages, but he still read it two or three times during his imprisonment. He also planted a papaya tree, which took a year to produce fruit.

"You don't give up, but you give up thinking about the future," Rodriguez said.

In December of 1944, relief finally came when the Japanese guards abandoned their posts as the Americans began to close in. Rodriguez joyfully watched American planes overhead chasing the Japanese.

In January of 1945, the 6th Ranger Battalion rescued Rodriguez and his fellow soldiers. The rangers infiltrated 30 miles behind enemy lines to carry out a surprise raid on the camp in order to free American prisoners.

Rodriguez knew then that his return to America was imminent.

After coming back from the war, Rodriguez got married and was offered another job at the New Mexico Timber Company. The owner allowed him to attend the local college before starting, and after graduation, he successfully became a manager, eventually overseeing 300 employees.

"I really was able to patch up my life after I came back," Rodriguez said. "I have trouble, but I've been able to cope with it."

Mr. Rodriguez was interviewed intermittently in Albuquerque, New Mexico, from January 23, 2002, to January 31, 2002, by Brian Lucero.