By Lynn Maguire

Rafael Fierro graduated from a small Texas high school in May of 1939, hoping to go to college on a basketball scholarship; but rather than donning a basketball jersey, he put on the uniform of a U.S. soldier.

"I went to the Sanderson [,Texas,] courthouse and signed up as a volunteer," wrote Fierro in comments to the Project. "On February 20th, 1941, I received orders to report to Ft. Bliss [in] Texas ... for boot camp."

Fierro described Sanderson as a "small railroad town of about 900 residents" during the 1920s. Fort Bliss was 300 miles northwest of Sanderson in the considerably larger city of El Paso, Texas.

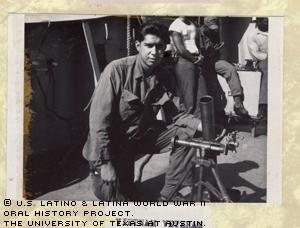

At the age of 21, he was assigned to the 1st Cavalry Division, 5th Regiment, Troop C and made friends easily.

"I basically got along with everyone," Fierro wrote. "I guess because we were all going through the same thing, homesickness, new people, and the hard training."

It wasn't all work, as he also managed occasional outings. One Sunday afternoon he went to the Plaza Theater to watch "Cabin in the Sky" and met a girl named Mary De La Rosa. Two years later, in April of 1943, they were married at Sacred Heart Catholic Church in El Paso.

He also played football, basketball and was on the track team, participating in the 200-yard dash and the mile relay.

"I not only had to go through the basic training with the rest of the recruits, I also practiced and played with the athletic teams," Fierro wrote.

He was playing football in Carlsbad, N.M., when he heard the news about Pearl Harbor. He and his teammates were immediately put on a bus back to Fort Bliss, where they started mobilizing for war.

"This included getting equipment and training ... My division was then sent to maneuvers in Louisiana in 1941 and in 1942," Fierro wrote.

"In June 1943, we were alerted to go to the Southwest Pacific Theatre," he wrote. "I arrived in Australia in July and started training for six months.''

Six months later he was in New Guinea. He went from New Guinea to the Admiralty Islands, then to Leyte Island, where he fought the Japanese. General Douglas MacArthur ordered his unit to move straight to Manila and liberate Allied prisoners of war in Santo Thomas, Fierro wrote.

There, a Sergeant Roybal asked Private Fierro to fill in for a typist clerk at headquarters who was ill.

"The captain would dictate letters to me and I would type them, these would be letters sent to the families of soldiers killed in action," Fierro wrote. "We then moved to Manila City and engaged in house-to-house fighting."

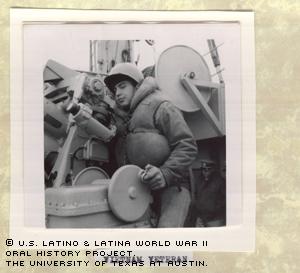

Soon after, his unit moved to the Philippine Islands’ Lucena, where the men waited for several weeks before receiving orders to get "new equipment and clothes and to get ready." They were told they were going to make a landing on the Japanese coast.

"We were told that 40 percent were going to be casualties because the Japanese were putting up some heavy fighting and were hiding in caves waiting for us," Fierro wrote.

But before the scheduled invasion of Japan, Fierro learned he’d accumulated enough points to be allowed to go home.

"I was told to turn in all of my equipment and I was sent to a station to wait for a ship that would bring me back to the states," Fierro wrote.

When he arrived in San Francisco, he heard the news the Japanese had surrendered.

"For me, the war was very hard and sad," Fierro wrote. "Some of my closest friends were killed."

His only brother, Bernardo Fierro, of the 9th Division of Company B, 47th Infantry, was killed in action in Germany on March 18, 1945, only four months before the war ended. Bernardo was married and had two small daughters.

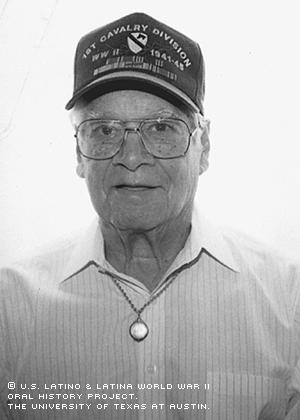

Fierro was awarded a Bronze Star, Good Conduct Medal, American Defense Medal, WWII Medal, and Atlantic Pacific Campaign Medal with a service of stars. He was honorably discharged from the Army on August 20, 1945, at the rank of Private.

Fierro and his wife Mary raised six children; all three of their sons served in Vietnam, and all returned, with honorable discharges. The Fierros celebrated their 60th wedding anniversary on April 4, 2003.

"Over the years I have seen quite a few changes in the way Latinos are treated," Fierro wrote. "I have since experienced many changes, especially in our daily lives."

Fierro recalled that in his small home town, a street separated the Anglos and the Mexicans Americans; the post office, stores and movie theater, where Latinos were restricted to the balcony, was on the Anglo west side. Even in church, at St. James Catholic, Mexican Americans sat in the back. Hispanic children attended a segregated elementary school -- an old wood structure; the Anglo school was red brick. Those Mexicans Americans who did get to high school went to Sanderson High School, along with Anglos.

"I had a hard time because I had never really been around Anglos," Fierro wrote.

When he became active in athletics and traveled with his teams, he once ate his hamburger in a car, because the restaurant where his basketball team ate had a sign that read, "No Mexicans."

But situations weren’t always negative: At a different tournament in Ozona, Texas, coaches rewarded his ability and dedication by crowning him "Most Valuable Player" and "All Tournament Player" for his Ozona High School team.

"I couldn't believe it," Fierro wrote. "I remember everyone clapping and cheering when they announced 'Number Four from Sanderson, Rafael Fierro.’

"This is one moment that stays close to me," Fierro said. "I can't explain the feeling, even if it was just for a moment."

Mr. Fierro was interviewed in El Paso, Texas, on October 23, 2003, by Elizabeth Flores.