By Amy Bauer

Aside from a move at 8 months of age, Raul Chavez had never traveled more than the 20 miles from Los Angeles to Catalina Island.

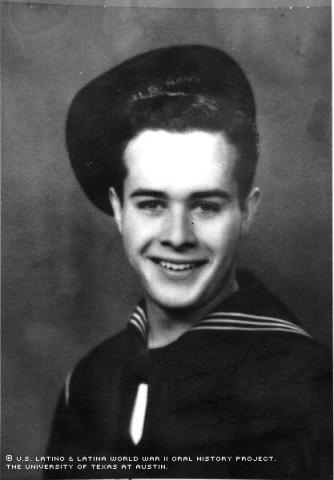

Born on Valentine's Day in 1926 in Chihuahua, Mexico, Chavez moved to East L.A. when he was an infant, during the Great Depression. His father, also named Raul, was a volunteer lieutenant in the California Militia State Guard and, thus, contributed to the war effort.

"I remember when I was going [to war] myself; he got a broomstick out and taught me the Manual of Arms," Chavez said.

As a youngster, Chavez had early exposure to what he calls "mainstream activities" while attending an All Nation's Club, which housed many other immigrant children.

"We didn't feel any discrimination. The discrimination we perceived was always very, very subtle," he said.

"I was a member of the Boy Scouts for four years as a kid, never dreaming that someday I would get a monthly paycheck from the Boy Scouts of America as a full-time executive," he added.

Chavez said he was involved in launching the first Outreach to Hispanic Kids for the Boy Scouts of America, and that he considers his 17 years of work with the organization a "real honor."

When Pearl Harbor was attacked by the Japanese in 1941, Chavez and his friends heard the news on the radio as they were coming home from a senior high school picnic. He said two things immediately came to mind: first, "Where's Pearl Harbor?" And second, "If we go to war, I hope it lasts long enough that we can be in it."

He said he now realizes how naive he was.

After high school in 1943, most of the boys in his class left for war, but not Chavez.

"I was younger than all of the other guys, so I had to stay until I turned 18," he said.

Raring to go and support his country, Chavez said he attempted to enlist early but learned that because he was not yet a U.S. citizen, he couldn’t volunteer until he turned 18. The day after his 18th birthday, he registered to go to war and joined the war effort on March 1, 1944.

He chose to enlist in the Navy, and his first stop was San Diego Naval Training Base in San Diego, Calif., where he completed a month of boot camp.

"Our training was reduced to one month from three because they were trying to get us out of the way and over there," Chavez said.

After completing basic training, he was off to Norman, Okla., for six months of naval technical training. There, Chavez learned how to work on aircraft engines, repair the metal fuselage and even learned to sew on canvas for the wing flaps and tail. Some of the planes back then still used cloth on the tail section; today, metal is used.

These training sessions were a lot of hard work, but he remembered that pranks were always being pulled.

"It's not all grim and guts and blood and death and mud," Chavez said.

The first encounter Chavez said he had with discrimination was when he took a General Classification Test to qualify for officer school. He placed second highest in his company. When he arrived at the enrollment offices, it was discovered he was a Mexican citizen. That was the end of his chances. It was a U.S. rule that you must be a citizen of the country to be an officer.

"I went all through school, all kinds of activities ... nothing ever required that I be a citizen until that moment," Chavez said.

Next for Chavez was what he called a double dose of aerial gunnery school. Someone made what he described as a "snafu," so his class took its first course in Whidbey Island, Wash., and then an identical course in Jacksonville, Fla. He learned, and learned well, how to shoot from a moving plane and hit a moving target.

After completing his second session of gunnery school, Chavez and his comrades headed toward Banana River, Fla., now known as Cape Canaveral.

"We hardly knew each other. It was the first time to begin flying as a crew," he said.

His crew flew in large seaplanes called PBMs, and their first trip was an overnight navigational over-water flight to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Chavez described the plane as a "flying whale with [huge] wings that go on forever."

PBMs only landed on water, and they could carry about 4,000 pounds of bombs. The mission of the aircraft was to search out enemy subs, locate and rescue lost American fliers and haul goods such as milk and mail.

The crew continued to do operational flying in Hawaii in March of 1945, where more training was provided. As a flight engineer and gunner, Chavez was in charge of the preflight procedures such as checking the flight engineers panel and flaps and starting up the engines. Finally, after weeks of firing machine guns, shooting at aerial targets, surprise mayday runs and preflight checks, Chavez and his crew were off to battle in Okinawa.

The plane stopped at several islands along the way, including Kwajalein and Eniwetok, where Chavez reports, "not a single palm tree was left after the invasion." The crew then landed in Saipan, which the U.S. had already conquered. Here he slept in Quonset huts and began to patrol for Japanese submarines. "I saw endless fleets of B29 bombers going to bomb Japan. Fleets of 400 to 500 planes just burning up the whole Japanese empire."

Chavez never got into any combat situation and is grateful. His most painful memory from the war is losing his best friend, Bobby Johnson of Los Angeles.

"Everybody has a best pal in the war," he explained.

One December day, an officer came around the ship recruiting a volunteer crew to go take some pictures of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It was a slow day, and Bobby volunteered. His plane crashed into a mountain that afternoon.

Chavez said he had the responsibility of going through Bobby's locker and sending his personal belongings to his parents. He still goes to pay his respects to Bobby, whose remains are buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

After the war, at 22, Chavez became a registered actor at the Pasadena Playhouse School of Theater and stayed there for three years. He had roles in many Spanish-language films and commercials and did voice-overs for the likes of Cap'n Crunch and Ross Perot. He also played a Native American warrior who died in Tonto's arms on one of the first Lone Ranger episodes. Years later, his casting agent continues to call if a part comes up.

Chavez now lives in Houston with his wife, Doris Fields de Chavez. He met her at a USO club in San Diego after returning from the war. While dancing, he had to cut in dozens of times, but finally got his girl. They had only one date before he was sent to Norfolk, Va., then Bermuda, to complete his time in the service. He mailed her the engagement ring and hurried back to her home in San Diego to get her response.

"I took military planes, a ferry, a taxi ... I was dying to see my sweetheart," he said. "I get to her house, I ring the door, it opens, I walk in and there is a sailor in uniform," Chavez said. "I thought the world had ended."

Luckily for Chavez, it turned out to be her cousin.

"To this day, I haven't forgiven him, said Chavez, laughing at the memory.

At the time of his interview, he and Doris had been married for more than 60 years.

Mr. Chavez was interviewed in Houston, Texas, on August 28, 2001, by Paul R. Zepeda.

Mr. Chavez was interviewed in Houston, Texas, on August 28, 2001, by Paul R. Zepeda.