By Lena Price

Placido Salazar had a choice.

He could have gone to the bunker, where he would have been relatively safe from the mortar attack raging outside his base in Bien Hoa, Vietnam, in 1965.

Or he could attempt to rescue his commander and a fellow soldier, who were recovering from injuries and illness in their mobile sleeping quarters several yards away from the command post where he was on duty.

Salazar didn't have time to think about his decision. He rushed to the men, and although he was only 5-and-a-half feet tall, threw an arm of the 6-foot-5 Col. William Forehand over his shoulder, and half-carried him to the bunker. With explosions all around them, he made it back to the safety of the bunker, but he wasn't as lucky when he went back for the second soldier, Lt. Col. Jack Carr.

"One of the rounds landed real close to me," Salazar said. "It knocked me off my feet, and I landed on my head."

Aside from a cut on one of his hands, Salazar did not notice any other injuries. He hauled the second soldier back to the bunker.

"It's a no-brainer," Salazar said. "I didn't do it because I was brave or because I was a hero. If anything I would say I was more of a coward, acting out of fear getting killed."

After the attack was over, Salazar's commander nominated him for both a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star with a "V" for heroism. Salazar said he was embarrassed about the Purple Heart nomination because, as far as he knew, the only wound he got from the attack was the cut on his hand.

But after the attack, which happened about two weeks after Salazar got to Vietnam in August 1965, he said he suffered from severe and almost constant headaches and pain to his spine, from the neck down.

"It felt like I had loose marbles in my head that were rubbing together," Salazar said. "Later on I found out that I had fractured some vertebrae when I landed on my head."

Salazar eventually had surgery to correct the fractured vertebrae, but not until 2009, after at least five neurosurgeons had refused to operate on him. A sliver of bone from one of the vertebrae was pushing into the spinal cord and they feared that removing the fragment would cause bleeding that could reach his brain and kill him. If he had known the extent of the damage, Salazar said he would have pushed harder to receive the Purple Heart his commander wanted to award him.

As for the Bronze Star, Salazar learned from a fellow soldier that the recommendation paperwork was destroyed by a colonel at his home base of Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, in Arizona.

"This colonel didn't know me and I did not know him, but only because I was a Mexican, he ripped the nomination to pieces."

Salazar said he was not surprised to hear what happened to the application because he had observed instances of blatant racism in the Air Force, even during his tour in Vietnam.

He spent four months stationed at the Air Force Base in Bien Hoa but often traveled through the jungles of the country. His unit, the 4080th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing, was responsible for transporting documents and other classified items between his base and the base in Saigon. There was minimal shelter in the jungle, and he was constantly exposed to Agent Orange. Salazar saw his comrades die in combat and years later began to see his friends come down with mysterious illnesses from exposure to the chemical.

"I don't think there is anything that could have prepared me for war," Salazar said.

After his tour in Vietnam, Salazar relocated to a base in Thailand. His duties were drastically different after he left Bien Hoa; this time he was responsible for clerical and administrative work.

Upon returning to the United States, Salazar continued his Air Force career for more than a decade. He was assigned to Randolph AFB, in San Antonio, for eight years, and also had stints in Hickam AFB, in Honolulu, Hawaii; and Kelly AFB, also in San Antonio, before retiring in October 1976.

When Salazar was growing up outside the small town of Edcouch, Texas, in the Rio Grande Valley, his father owned a small grocery store and a plot of land. Salazar was one of seven children, however, and the income was not enough to support his large family.

"There was a middle class, a lower class and then there was us right below the poor people," he said.

Every day after school, Salazar and all of his siblings left the one-room steel shack they lived in to chop weeds in neighboring cotton fields. Before school, Salazar would deliver milk and after school he sold fruit and tacos at local beer joints. He said it was especially difficult growing up during World War II because everything was rationed and food was scarce.

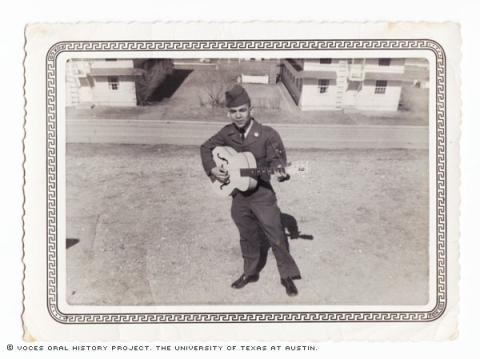

Although Salazar did not have much free time, when he was 7 years old, his father taught him how to play the guitar. He played music in the evenings and eventually started touring West Texas to play talent shows, where he never came away with anything less than first place.

Salazar applied the same level of dedication to his schoolwork. He lived 7 miles from his high school and did not have access to a car, so every day he walked or hitchhiked back home after band practice.

He didn't think about quitting until he reached 10th grade and was about three credit hours away from earning his diploma. Because he knew he would not be able to pursue a college education or find a decent job, he decided to drop out and join the military in 1954. He applied to all four branches, and the Air Force was the first to respond.

Salazar made a career out of the Air Force, and he said it was enough to give his family everything they needed and some things they did not need. When he retired in the mid-'70s, he found work as a radio and television host, touring on weekends to sing in Mexico and Texas and occasionally in places farther away, like California, Ohio and Michigan. He also worked as a licensed private investigator.

In later years, Salazar remained an advocate for veterans' rights, becoming active in the American GI Forum. During a town hall meeting in 2008, he confronted then-presidential candidate Barack Obama about the need for a full-service VA hospital for veterans in the Rio Grande Valley.

More than three decades after he left the Air Force, and following a long struggle working with veterans' organizations, Salazar finally received his Purple Heart and Bronze Star at a ceremony at Randolph AFB on Feb. 15, 2013.

Mr. Salazar was interviewed by Lena Price in Castroville, Texas, on Nov. 6, 2010.