By Rachna Sheth and Sandra Taylor

Philip James Benavides had a dream when he joined the United States Marine Corps in the summer of 1941: He wanted to make music. But within three and a half years, particularly after three months of torture in a Japanese prison camp, he’d lost those physical abilities that had made him a standout musician since childhood.

Although Benavides sustained relatively minor injuries, their effects left him unable to function as a musician. The physical torture he endured during his captivity left him unable to control his lips and fingers the way they are needed for playing the French horn. He also lost much of his hearing because of the years of loud noises on the battlefield.

"It did the job," Benavides said. "I was unable to function again as a musician ... I could listen to music and I would usually be half a tone behind the rest of them ... I was getting completely tone deaf so I just gave [music] up completely."

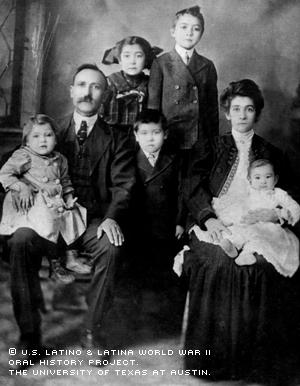

Benavides was born May 1, 1921, in Austin to Manuel Benavides, a traveling musician, and Guadalupe Estrada Benavides. Manuel died when Benavides was only 4, the second-youngest of 12 children.

Guadalupe began working as a housekeeper. And lucky for Benavides, one of her clients, Joseph Koenigseder, was a teacher at the Austin School of Music. Guadalupe arranged to have Koenigseder provide free music lessons for Benavides in exchange for laundry services.

Benavides graduated from St. Edwards High School in Austin in 1941 and began studying at St. Edwards University, where he received paid tuition to pursue the priesthood. In June of 1941, however, Koenigseder took Benavides to Houston for an audition with the Marine Corps Band. And five months later, Benavides found himself on a train headed to Camp Pendleton in San Diego, Calif., to begin five months of basic training.

"That's how I came about joining the Marine Corps -- to go into the band," he said.

Upon completing basic training, Benavides was assigned to the band at the San Diego Marine Corps Base, and was given the rank of Corporal.

After serving aboard the U.S.S. Essex and being given further training, Benavides was sent to Auckland, New Zealand, for his first assignment in June of 1942. In New Zealand, his unit performed in parades. But soon, his duties as a bandsman became secondary; when his band was called upon to act as first-aid corpsmen and medics in the summer of 1942.

The Marine bandsmen were to alleviate the shortage of Navy corpsmen during the early stages of the Battle of Guadalcanal. Band members in the military have as a secondary job to help medics however possible, a fact of which the Marine Corps is particularly proud. All Marines are first infantrymen and undertake another field of expertise in a secondary role.

Benavides says he never anticipated being involved in nursing wounds and serving as a stretcher-bearer.

"We did first-aid duty to the best of our knowledge -- sometimes it wasn't good enough," he said. "We weren't trained in it ... we did anything we could to stop the bleeding, ease the pain ... on the job training."

Circumstances forced the 9th Marine bandsmen into combat as they headed back to the frontlines to replenish supplies and retrieve the wounded and the dead.

"[There's] no way to put it in words," Benavides said. "It was unbelievable. The more we battled ... I guess you could say you got used to it."

Once the Navy pulled out of Guadalcanal, survival became more than dodging enemy fire. Food was so scarce that one meal a day was considered lucky. Hungry and tired, the Marines would eat anything they could scrounge up, including roots and grubworms.

In keeping with the American's island-hopping strategy, Benavides was sent back to New Zealand, then back to Guadalcanal, then to New Georgia, in the Solomon Islands, in the spring of 1943. The military operation was constructed to secure Munda Airfield; Benavides' division arrived to bolster the inexperienced 45th Army Division. A month into the operation, however, Benavides contracted malaria and was sent back to Auckland to recuperate.

On Nov. 1, 1943, Benavides' unit landed in Bougainville. As battle ensued, he was on his way to retrieve casualties when a Japanese mortar exploded nearby.

"I only remember flying through the air and trying to protect myself," he said. "These banyan trees grow with these huge roots. I hit one of the roots ... and that's the last thing I remembered for three days."

Benavides recalls a doctor saying his eye was partially out. Since then, he has lost all vision in his left eye and covers it up with an eye patch.

After four weeks of recuperation, Benavides was sent into battle again -- this time to the Battle of New Britain in December of 1943. One day, while on patrol with 11 others, he and his fellow soldiers returned to their campsite to find the unit had evacuated the area and Japanese were there. The Japanese immediately took him and the other men as prisoners.

"That's where my torture started," Benavides said. "They were trying to find out what I knew about what the next move was going to be."

For three months, Japanese soldiers tortured him with electric shocks, by beating his legs, back and face with bamboo sticks, and by forcing him to stay submerged to his neck in a leech-infested pond.

In March of 1944, the Japanese heard noises in the jungle and knew Allied Forces would soon be arriving, so they began shooting the American prisoners. One Japanese officer put his pistol to Benavides' head and pulled the trigger twice. Nothing happened. Having lost his will to live, Benavides showed the Japanese soldier the gun's clip wasn’t in. The officer snapped his clip in and, again, shot twice. Still, nothing happened.

"I was thinking, 'God's on my side, I wonder why,'" Benavides recalled.

When the Australian Allies arrived, they rescued Benavides and the four other surviving prisoners of war. Those POWs were sent home on a hospital ship.

The boat arrived in San Francisco, Calif., shortly before Christmas of 1944. Completely covered with people, the Golden Gate Bridge welcomed the soldiers back home with a shower of white carnations, flags and roses.

"The ship slowed ... to give us all a chance to really get the full impact of what had happened," said Benavides; "one of the most beautiful things that ever happened to me."

Benavides was treated for his eye injury and, later, for post-traumatic stress disorder. He was honorably discharged from the Marines on April 20, 1945, at the rank of Gunnery Sergeant, later receiving a Bronze Star, Purple Heart and World War II Victory Medal, among other honors. But life was still difficult for the first three years out of the Marine Corps.

"After I left the Corps, I was so discouraged and so out of it, I didn't care if I got a medal or not," said Benavides about his decorations. "I just did my duty like it was supposed to be done."

Benavides married Isabel Dominguez in 1946, with whom he had six children, including one from her previous marriage. The relationship ended in divorce 10 years later.

He married his second wife, Maria Uranga, in El Paso, Texas, in 1961. Together they had four children.

Marie died in 1984, and Benavides now lives with two of his children, Mary and Armando. He says he feels God kept that pistol from discharging when he was a POW so he could live to take care of Armando, who suffers from Downs Syndrome, and Mary, who is epileptic.

After the war, Benavides worked mostly as a mechanic and moved to El Paso in 1967 for job opportunities.

He says he hopes people 150 years from now will see that Chicanos did their duty in WWII.

"I know there are areas in the United States where our people are looked down on, so we have to fight," Benavides said. "Not with guns and knives, but with our cabezas."

Mr. Benavides was interviewed in El Paso, Texas, on July 7, 2003, by Robert Rivas.