By the Voces Staff

When the Uvalde High School walkout began in April 1970, Olga Muñoz Rodriquez was a young mother working for the telephone company. While her son was not yet in school, she knew from experience the discrimination that Mexican-American students faced, so she joined the protest.

The walkout fueled her commitment to civil rights, which would lead to her becoming a community leader, radio commentator and newspaper publisher in Uvalde, which is about 80 miles southwest of San Antonio, Texas.

Years later, she would say that the walkout, which involved about 500 students and lasted for six weeks, awakened activism in the Mexican-American community. Parents joined students in marches and meetings, sometimes at risk of losing their jobs because their employers opposed the walkout.

“People were more emboldened to do things for the community,” Rodriquez said, although the changes spurred by the walkout were gradual.

Rodriquez’s family originated from Nava, Coahuila, a Mexican border town about 30 miles southwest of Eagle Pass, Texas. Her father was a blacksmith who built wagons in a backyard workshop but who decided to move to the U.S. for better opportunities. On Oct. 12, 1953, the family crossed over. “Eagle Pass was our Ellis Island,” Rodriquez said.

The family settled first in El Indio, where Rodriquez went to a two-room country school with just three teachers. “They were very nurturing,” she said. “We learned English very fast.”

When her father got a job at White’s Mine in tiny Dabney, the family moved into company-owned housing. Rodriquez went to school in Uvalde, where the atmosphere was not as welcoming.

“In those days, the schools were pretty much segregated,” she said. “You always felt the division; we didn’t play at each other’s homes.”

She recalled one episode when she was at Uvalde High. To elect class officers, students would go to the auditorium, nominate classmates for various positions, and then teachers would ask for a show of hands to determine the outcome. She recalled one time when she was nominated for every office but didn't win any.

“The teacher that counted the votes for the Anglo students kept her number silent until the teacher that counted for Mexican kids. The Anglo (vote) was announced first, and ours were always lower,” she said. “We could tell that it was not a fair election; there was nothing on paper. It was just like random counting.”

One time, Rodriquez led other Mexican-American students in a walkout from the auditorium. She got a lecture from the vice principal but faced no other consequences.

After high school, she went to Southwest Texas Junior College. “By the time I graduated, my father got sick and could not work so we all needed to pitch in. My mother was brought up so strict, so very protective of us girls, she could not possibly accept me going away to college. So junior college was all I got until after I got married and was able to go back.”

She married Richard Rodriquez on Dec. 3, 1966, after he had returned from serving with the Navy in Vietnam.

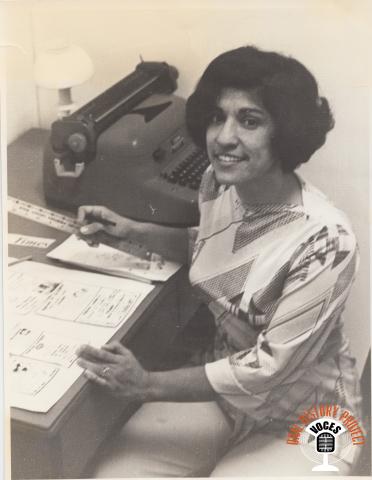

She was working for Southwestern Bell Telephone Co. -- only the second Mexican-American worker at the company in Uvalde -- when the school walkout began.

Mexican-American parents had been complaining to the district about issues including poor maintenance of the schools their children attended. “Dalton (the Anglo school) got landscaping, paved driveways, the grounds were kept. Robb (the Hispanic school) had minimal maintenance. The bathrooms were in really bad condition; there weren’t enough teachers that spoke Spanish.”

“Things were already brewing” when the district refused to extend the contract of George Garza, a teacher who had advocated for Hispanic parents, which irritated school administrators. The contract issue “was the straw that broke the camel’s back,” Rodriquez said.

She remembers a tense school board meeting where police officers with rifles were positioned on the roof. The next day, April 14, 1970, students started walking out. Rodriquez became secretary of the Mexican-American Parents Association. She would write letters to the Uvalde Leader-News “to express our side.”

Some parents kept their children in school, fearful of angering employers who opposed the walkout. She worried about her own job, and the hostility from some co-workers was palpable.

A co-worker would read Rodriquez’s letters in the paper and make comments just loud enough for her to hear. “I remember her saying, 'I think they should all burn them at the stake, like that man in Rocksprings.'” The reference was to the 1910 lynching of a Mexican farmhand accused of murder in the town about 70 miles north of Uvalde. A white mob dragged him out of jail and burned him alive.

After MAPA was formed, some German-American parents formed the German-American Parents Organization, and one member wrote to the newspaper that if Hispanic parents “didn’t like their children being discriminated because of the difference in their skin, he recommended that parents powder their children’s faces before they sent them to school,” she said.

Rodriquez responded in kind with a letter that said, “If you don’t like being in a community with Mexican-Americans, I suggest you hitch up the old covered wagon and go back East and row your boat back to where you came from.”

As the walkout continued, the school district said that students who stayed out would either be held back a grade or not allowed to graduate. “We could not go back,” Rodriquez said. “We would rather have the kids lose a year and move forward with the changes.”

The road forward was not easy. In 1973, the Texas Legislature passed a law requiring districts to offer bilingual education. When the Uvalde district started its program, “We found out they had placed all of the disabled students in bilingual education. Those poor teachers weren’t prepared to deal with handicapped children. They (school administrators) wanted it to fail.”

The owner of the radio station KVOU had been calling Rodriquez for several years about how he could better serve the Mexican-American community, in order to keep his FCC license. In 1976, Rodriquez suggested that he give her a 30-minute weekly program in Spanish, and to her surprise, he agreed. She and Ramon Velasquez started “Comentario,” which aired on Sunday afternoons. It was a mix of commentary on topics such as school segregation and local government, laced with humor from Velasquez about issues such as poor maintenance of streets in Mexican-American neighborhoods.

“All of these things came about as a result of the walkout,” Rodriquez said.

So did her next step: starting a newspaper, building on the activism the walkout had inspired in her.

“I was so frustrated,” she said. “My radio show had been taken away” because advertisers pressured the station owner. The Uvalde Leader-News was "messing up my letters” by inserting errors “to make them look ignorant.”

In envisioning her newspaper, she said, “I wanted a voice for community, but I wanted it in English and Spanish. I wanted us to understand each other.”

She got some advice from the editor of the Chicano Times, an alternative newspaper in San Antonio, and was ready to launch El Uvalde Times in November 1978.

“I left my job at the phone company and with my last paycheck I started my business,” she said. She was heartened by the local businesses that bought ads, giving her enough capital to start the paper -- twice a month at first, then weekly.

“We were focused on education issues, the wrongs committed by our school administration. I covered the school board meetings but also city and county government meetings,” she said. Rodriquez also wrote a column in English and Spanish that opened up a dialogue with the Anglo community. “After the brutal hatred that the school walkout brought out, the newspaper was bringing us together.”

She was proud of the social coverage that reflected the Mexican-American community -– the First Communions, the weddings, the quinceañeras. Those stories ran in the main part of her paper, “not in the grocery section, like they would do at the Uvalde Leader News.”

The circulation rose to 3,000 copies, but the advertising was not enough to pay the bills, and she closed the paper in 1980. She returned to the telephone company and was transferred to San Antonio in 1982. There she started another paper for Uvalde with the same name in 1991, but closed it 18 months later; it was very difficult to juggle her job, her family and the newspaper.

She finally was able to earn a bachelor’s degree in business rom the University of the Incarnate Word and and a master's degree in management from Our Lady of the Lake University, both in San Antonio.

She remained tied to Uvalde through family, friends and her church, and continued to watch the city evolve. President Lyndon Johnson’s war on poverty allowed the town to get federal block grants for community improvements. Her brother Roy –- once a student protester -- became an attorney in private practice and then Uvalde County Attorney. He eventually was elected district attorney for three counties. “I saw that as an incredible event in Uvalde,” she said.

She credits the courage of Mexican-American parents who stood up to the Uvalde establishment. “Their bravery allowed some compassion to filter through and some changes have come about because of that.”

Mrs. Rodriquez was interviewed by Alfredo Santos in Uvalde, Texas, on April 9, 2016.