By Amy K. Williams

Down in a foxhole in the midst of World War II Germany, Noé Sandoval, Jr. looked up to see a soldier standing at 6 feet 4 inches staring down at him saying, “Get the hell out of there. This is my foxhole. Go dig your own.”

It was Sandoval’s first day in combat with the 10th Armored Division’s 61st Armored Infantry Battalion. All the soldiers had jumped out of the trucks and had been told to dig themselves foxholes. Sandoval saw an empty one that looked like it had been dug just for him, or at least it looked that way until the other soldier arrived. He laughs looking back on that day.

“I started digging pretty fast,” Sandoval said.

Before ever creating his first foxhole, he experienced a taste of what life during war was going to be like. On the way to join his outfit, he passed a field littered with the bodies of hundreds of GIs. It was a harsh sight for a boy of barely 18 coming from a peaceful life in Laredo, Texas.

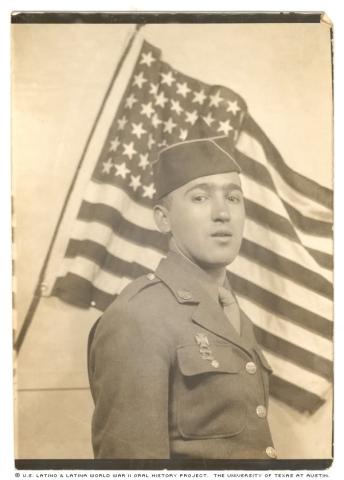

Just two short months after his high school graduation, Sandoval enlisted in the Army Enlisted Reserve Corps on July 26, 1944. He was only 17 when he signed up, and was called to active duty four days after his 18th birthday. His 37-year career with the United States military was beginning.

“I’ll never regret it,” Sandoval said. “I thought it was an obligation to join the service in World War II.”

Some members of his family encouraged him to go to Mexico, but Sandoval says he merely laughed at them.

It just so happened that his 38-year-old dad, Noé Sandoval, had recently been drafted, so father and son went for their physical examinations at the same time; however, his father didn’t meet the physical minimums and wasn’t required to go to war. Sandoval says his mother, Ana Garcia Sandoval, was broken-hearted he was going to war, but he felt he owed something to his country for the life he had.

The life for which Sandoval was so thankful began changing rapidly as he went through basic training and then became entrenched in military life. He recalls a day when they were taking a small town and his rifle quit working. Sandoval’s company commander handed him his pistol and said, “Go get ’em.” The next day he was issued another rifle. He says he remembers every moment of only having that pistol to defend himself.

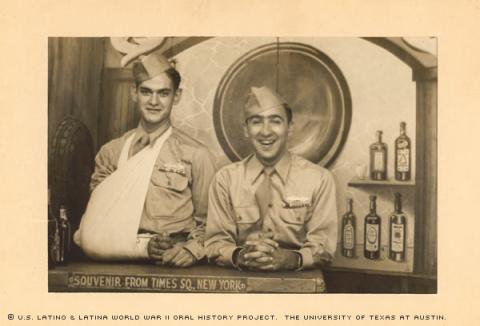

Sandoval was discharged from the Army on Feb. 6, 1946, at the rank of Private First Class. After returning home, he joined the El Paso Border Patrol.

The people working there didn’t want to hire him initially because he was Latino, but Washington forced the El Paso Border Patrol to accept him, says Sandoval, noting that this was one of the few times he ever experienced discrimination.

He also remembers a time with his father-in-law when they were trying to launch a boat at a ramp. A man told one of them sorry, but he couldn’t let him put his boat in the water there. He explained to Sandoval and his father-in-law that it wasn’t his decision; the people who owned the ramp wouldn’t allow it because he was Mexican American. Sandoval recalls not understanding how he could have fought for this country in WWII and still be seen as somehow un-American.

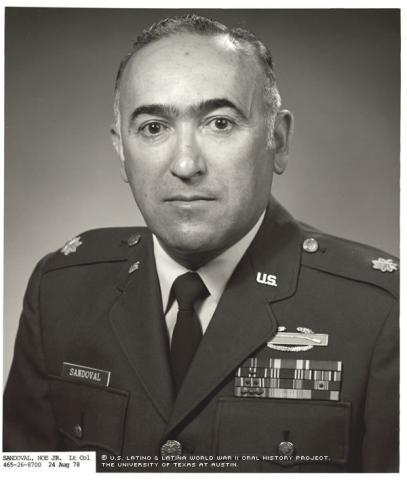

Once again, Sandoval showed his devotion to his nation when he requested active duty in 1962. He left his children and pregnant wife, Frances C. Sandoval, in November of that year to serve his country.

“I thought we were going to have war with Cuba,” said Sandoval, who ended up on the other side of the world instead.

After spending thirteen months in Korea, he returned home and remained active in the military until his retirement in early 1981. He says he’s very proud to have been a Latino officer in the Army.

“I’ve always loved military life,” Sandoval said. “I wasn’t happy until I was in uniform.”

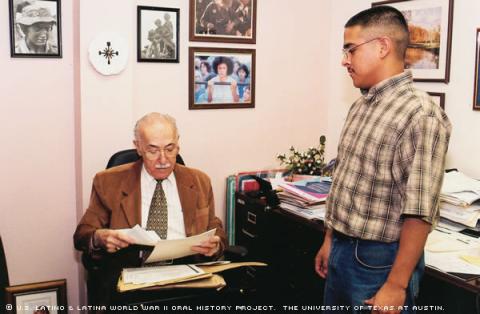

Mr. Sandoval was interviewed in San Antonio, Texas, on Nov. 6, 2004, by Julio Ovando.