By Erika Jaramillo

World War II veteran Natividad Campos says he felt like an old man by the age of 9.

Kidnapped by his father at age 3 and raised by his Spanish-speaking grandmother, Campos, the oldest son of four, had no formal education when in 1930 he entered St. Valentine Elementary School in Valentine, Texas.

“It was hard for me. I wasn’t use to being around so many kids at one time,” said the 87-year-old, born on Christmas, 1921.

Campos quit school at 15 to help support his family in Ft. Davis, the only town in addition to Valentine in West Texas’ sparsely populated Jeff Davis County. The native Texan and Mexican American knew how to read and write in Spanish, compliments of his grandmother, but he struggled with English for most of his adolescent life, not mastering the language until his induction into the Army in 1941, he says.

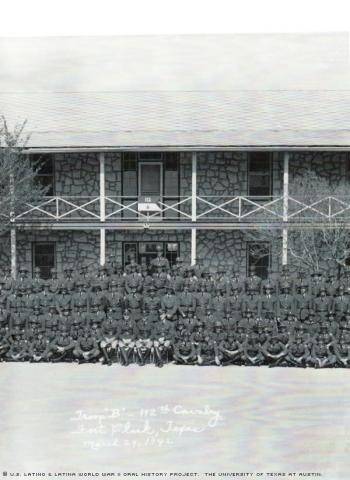

“When [Latinos] got together, we would automatically carry a conversation in Spanish, not in English, because we weren’t very professional in English,” said Campos about his recollections of the Cavalry. “So [the white soldiers] would give us hell and say, ‘you’re in the American Army, speak English.’ So I spoke English.”

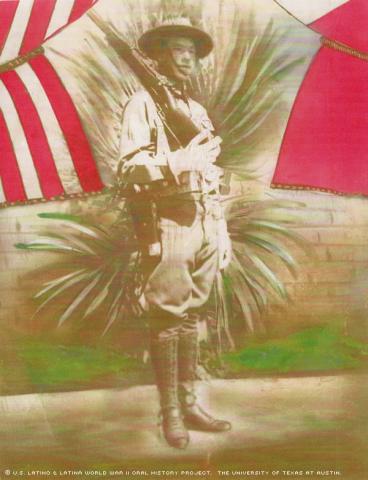

A restless Campos decided to volunteer for the Army at age 19. While his friends intentionally dodged the war by getting married, he says he was eager to serve his country.

“There was not much to do in the town I grew in,” Campos wrote after his interview. “Besides[,] I was at the age when you look for adventure.”

He even went so far as to lie about his birthday, “saying I was one year older, so my father did not have to sign for me,” he confessed during his interview. “[My family] thought I was crazy, because at that time, there weren’t too many Latinos going into the Army.”

According to the National WWII Museum in New Orleans, LA., however, approximately 250,000 Latinos served in the conflict.

Campos says he initially thought he’d be discharged within a short period of time. But then Dec. 7, 1941, rolled around, and he quickly figured out that wasn’t going to be the case.

“It was a Sunday. I went to the barracks to smoke a cigarette. Everyone was around the radio and they tell me the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. I said, ‘Where is Pear Harbor?’ I didn’t even know where it was. They said, ‘That’s in Hawaii -- that means we’re at war.’”

By 1942, Campos was shipped overseas to New Caledonia, a French island 800 miles off the coast of Australia. He was stationed there as a member of the 112th Cavalry Regiment for nine months, spending a lot of time riding horseback on the island due to the rough terrain.

“The Japanese had ransacked all over the Pacific at that time, so we had to protect the island,” he said.

Campos was discharged from the Army on August 18, 1945, at the rank of Private First Class. Although the G.I. Bill of Rights; which provided veterans with low-interest mortgages, unemployment insurance and, perhaps most significantly, financial assistance to attend college; had been passed the year before, he didn’t take advantage of it. Instead, he plowed right into the workforce

Campos says that despite a pattern of Anglos getting hired for higher positions at Asarco, a mining, smelting and refining company based in El Paso, Texas, he applied himself and climbed up the socioeconomic ladder.

“I started as a laborer,” Campos said. “They offered me a job at the lab and I took it. I told them, ‘I don’t know anything about chemistry.’ They said, ‘Well you don’t have to know, we’ll teach you.’ I thought, well, I’m not a chemist, but I’ll make myself one.”

Though he says he didn’t feel racial discrimination at work, he says he experienced it one night when he went drinking with friends at a drive-in movie theater.

“When you drink beer, you get hungry. So I told [my friends], ‘Let’s go to Monahans and get something to eat.’ They served us beer but not food. They told us, ‘No, we don’t serve Mexicans.’ I felt pretty bad because I felt I was just as American as anybody else,” Campos said.

Since the war, he has married twice and fathered six children, and says he’s fortunate they had more opportunities growing up than he did. His oldest son, Natividad Campos, Jr., earned a master’s degree in math and a bachelor’s degree in education. Natividad Jr. then earned a second master’s in Urban Development from Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas, Campos says.

“I’m proud of all my children’s successes, even the ones without degrees,” he said.

Though Campos says the situation for Latinos has improved, he has a few encouraging words for younger Latinos who may have to deal with prejudice on occasion.

“Don’t let them discriminate you,” Campos said. “Tell them I am just as good as you are or better.”

Mr. Campos was interviewed in El Paso, Texas, on September 1, 2007, by Beatriz Guerrero.