By Scott Reister

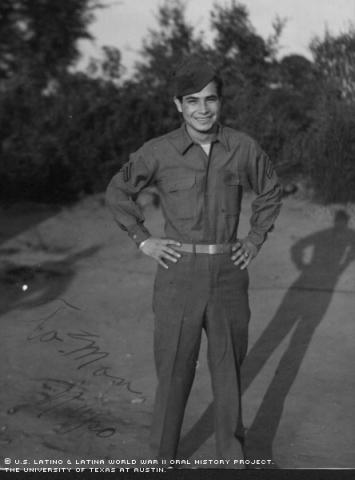

To become an Air Cadet in the Army's World War II training program, one had to display physical and mental superiority. Cadets had to be the best of the best, and follow a path of intense training in preparation for military service. Former Staff Sgt. Narciso Garcia knew he had what it took, including the ability to remain humble.

"Cadets were treated like ultra-special people," Garcia said. "Our superiors ... constantly built us up and told us how great we were. Some guys really believed it, but I never let it get to me."

After graduating from El Paso High in 1943, Garcia was accepted into the Air Cadet Program and began his training. Within two years he had become a

Staff Sergeant at the U.S. Army Air Corps and participated in crucial World War II operations. Garcia served as a tail gunner in a B-25 Mitchell bomber, flying 41 combat missions during his two and a half years of military service. As a member of the 340th bomb group, 488th Bomb Squadron, he flew tactical missions in Northern Italy with the objective of destroying bridges, ammo dumps, railroad yards, (fuel) tank farms and other facilities being used by the Germans.

"We were called 'bridge busters'," Garcia said. "We kept the Brenner Pass closed."

The Brenner Pass starts in Northern Italy, running through the Apennine Mountains from Austria into Northern Italy's Po Valley. At the time it was the only pass through the mountains into Austria, therefore it was a high traffic area for the Germans. Garcia and the bridge busters had the primary mission of destroying as many bridges as possible to keep the pass closed.

"We were constantly bombing the Brenner Pass," he said. "Any major bridge we would bomb unless our target in the pass was obliterated by weather, in which case, we would have an alternate target in Northern Italy's Po Valley."

The bomb squadron always faced danger from German anti-aircraft artillery at the target sites and en route to the target. Each mission, a fighter escort would accompany the bridge busters to the target, dissuading attacks on the bomber formation by enemy fighters.

"We would see German fighters at a distance, but they were considered only a nuisance, and that's what they were," Garcia said. "Once in a while they would fire, but then they would bug out and run at the first sign of return fire."

Some missions were more dangerous than others. German forces would sometimes anticipate an attack on these targeted bridges, and organize a stiffer defense. One particular mission stands out for Garcia. The mission, flown over Corsica, Italy, was supposed to be a "nickel" mission, or a "milk run," meaning the target was expected to be unguarded.

"There was supposed to be no flak (ground fire directed at the plane) at the target area," Garcia said. "But it had the highest concentration of (anti-aircraft batteries than) any mission we flew. We had a squadron of 24 planes and only 11 came back. The rest didn't necessarily go down, but they had to crash land or parachute in enemy territory, dodge possible capture by the enemy and wait for Air/Sea Rescue."

During the mission, Garcia saw the plane directly to his left get shot and go down in flames. His own plane had numerous holes throughout, a damaged engine, and a giant hole in the right wing, causing rapid fuel loss. Making it back to base was an uncertainty.

"We had the chance to crash land in Switzerland and possibly survive the crash and be confined in a neutral detention camp for the war's duration. We were a long way from base," he said. "We decided to try for home. On the way home the plane was real shaky and we had to shut off the damaged engine; but we kept going. We survived, and then had to wait out news on the rest of the planes' and particularly the survival and severity of injuries of the crewmen."

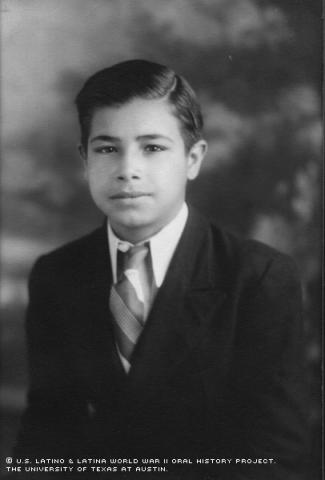

During his military service, which lasted from 1943-1945, Garcia relied on his military training and his ingenuity and survival skills. He had developed great ingenuity and inventiveness as a child growing up in El Paso, Tex., Garcia was very inventive and had a knack for building things. He was known as "el inventór" (the inventor) in his neighborhood.

To earn a bit of spending cash, he fixed things, such as bicycles, phonographs, sewing machines. He also worked in various grocery stores, a bakery and a fuel and feed story, which sold wood, coal, hay, oats, barley and other goods.

"People would lose the speed control on their phonographs, and the music would go too fast," Garcia said. "I just happened to know how to fix that mechanism."

Garcia would turn over part of his earnings to his mother, but she never used that money for household expenses, but would, instead, save it for him.

He enjoyed building things and seeing how they worked. Using a phonograph motor, he built a miniature merry go-round. The project evolved into an entire miniature carnival that was mounted on a four-by-eight piece of plywood.

"Kids would carry it around the neighborhood for people to see it," Garcia said about his mechanical creation. "I just enjoyed doing it."

Garcia had not planned on continuing any higher education after high school; monetary considerations made it impractical to get a college degree. He was drafted during his senior year in 1943.

"It was only after the war and the advent of the GI Bill that everyone knew I was destined to go to college," said Garcia, referring to the expectations of his family and friends.

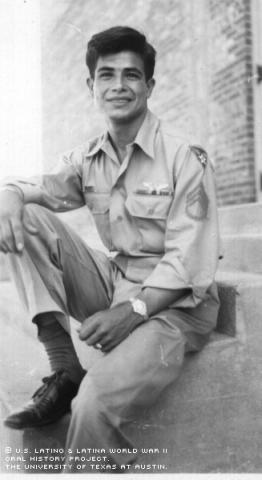

Following high school, the talented Garcia became an Air Cadet and remained interested in science, mechanics and engineering. His military training led him to several military bases around the country. After beginning in Fort Bliss, Tex., he moved on to Wichita Falls, Tex., for basic training before beginning cadet training with a Special Training Detachment at the University of Wichita at Wichita, Kansas.

"We were housed in the university dormitories and studied regular college courses such as English, history, government, math, physics," Garcia said.

The courses were oriented toward practical applications.

"Math and physics were particularly emphasized in a manner to give us a better understanding of mechanics, military equipment, the theory of flight, aerodynamics, navigation and ballistics," he said.

There were also emphases on ethics, personal grooming and respect for authority.

"We were also harassed night and day by superior officers, whom we called 'bottle cap generals,'" he said.

In his cadet class, only three out of a class of 400 were Hispanic. Garcia said he never had problems with discrimination, but in written comments after his interview, he acknowledged widespread discrimination against Blacks, who served in segregated military units. Also, he said, he believes that there were a large number of Hispanics were drafted and placed in "the most physically demanding and dirtiest jobs."

Being stationed in Wichita had some pluses. It gave Garcia a chance to take advantage of the highly favorable men to women ratio. Wichita had several aircraft and factories and supporting industries, but during the War, 80 percent of the aircraft workers were women. All the men between 18 and 36 had gone to the army. Most of the men left were elderly, married, middle-aged or students.

That left between 400 to 600 eligible bachelors and highly desireable cadets.

"There were 14 women to every man," he said. "You'd go to town and you'd be mobbed by women. They'd follow you around, whistle at you, and buy you dinner. I'd have three women sitting by me at a restaurant, and I'd move, and they would follow me."

Women at the laundry would write their phone numbers on the cardboards used to pack the cadet's starched shirts.

There were especially no problems with discrimination from the women in the town.

"When you're a cadet, they don't look at your skin," Garcia said. "All they looked for were the wings on your sleeves. When they saw those wings, they knew you were the best of the best in every respect."

Before beginning his combat missions, Garcia finished his training at Wichita Falls, and then made stops Lowry Field in Denver, Ft. Buckingham in Florida, and Greenville Airbase in South Carolina. While training, Garcia developed skills that would help him carry out his future duties.

"I became an armored gunner," he said. "I learned the plane, and all its gun positions and I learned the weaponry. I learned how a bomb is made, the wide variety of bombs available, how they are [fused] with engine speed which makes it possible to fire a machine gun through the propellers of the plan without hitting them. I learned everything about gun sights. I became an expert on the 50 caliber machine gun, its installation, maintenance and repair and its use.''

Garcia and his orderly behavior survived two and one half years and 44 combat missions. On November 6, 1945, he was honorably discharged.

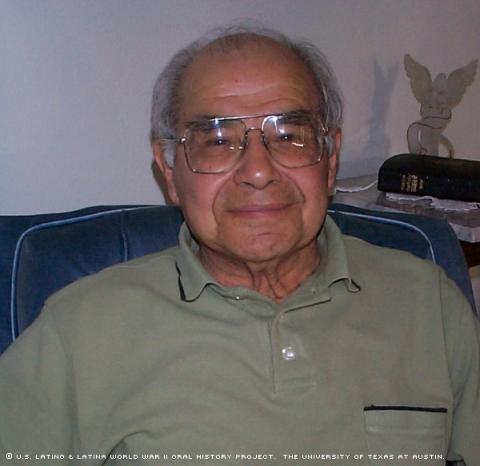

When he returned to El Paso, Narciso Garcia had come a long way. He had gone from fixing phonographs to fixing machine guns. From riding bicycles to flying planes. From helping his neighbors to helping his country. When he came home he also helped himself out. Garcia used the GI Bill to earn a Bachelor of Science degree in Civil Engineering from the Texas Western College in 1951. He worked as an engineer for the U.S. Corps of Engineers at the White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico, for many years before retiring.

Garcia married Frances Najera and the couple had two children: Michael and Loretta.