By Ana Cristina Acosta

For most Americans, walking down the street, entering a restaurant through the front door or going to the grocery store is routine. But for Mary Murillo, 75, who grew up at a time when Mexican Americans suffered blatant discrimination, those simple things weren’t always possible.

Murillo was born and raised in Austin, during a time when segregation and discrimination were part of daily life for Mexican Americans. She clearly remembers the days when walking in a predominantly white neighborhood was enough reason to be arrested if you were Mexican American.

"In this same street, in the other side of the river, they would call the police if we went there," Murillo said. "We knew we shouldn't go there."

During her early school years, Anglo children were served free lunches, while Mexican-American children brought their own bean-taco lunches, she said, recalling hiding behind trees, fearful of being taunted by the other children

"They started giving us lunch after a few years, but we had to wait until the white children would finish. Then they would call us, only then we could go inside the cafeteria," Murillo said.

It was worse when her mother was little. Her grandfather used to tell her that on hot summer days, he would drive all the way from the rancho, or ranch, to town to buy ice cream. On at least one occasion, however, the owner of the restaurant threw him out, telling him he didn't serve "Meskins," referring to Mexican Americans.

"We were kind of afraid to go just into any store. We wouldn't just open the door and go in like we would at the mall, because we were afraid they would throw us out," Murillo said.

"I don't know why they did this, they thought we were inferior I guess," she said with a laugh.

Even though some problems still need resolving, she believes Latinos have come a long way since the days when they couldn't enter some restaurants through the front door.

"I think it's gotten a lot better," she said.

According to historians, Latinos owe those advancements to some extent to Murillo and other WWII-generation Latinos, who weren’t willing to sit and wait for their situation to change, and, as a result, decided to change their own circumstances.

"We owed it to our children," she said.

They helped pave the way for younger generations of Mexican Americans, as well as set the stage for the civil rights efforts of the ’60s and ’70s.

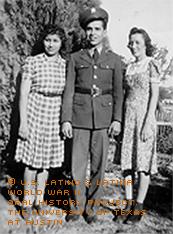

She firmly believes World War II had an impact on the treatment of Mexican-Americans. Her four brothers, her cousins and all of her friends from her neighborhood were drafted and sent overseas to fight, but when they returned, they found the same discrimination they faced before departing for the war.

They began to question the system and became more demanding of their rights.

"We were used to being in our place you know, we weren't very demanding," Murillo said.

But mindsets began to change when Latino soldiers returned from the war.

"There was more talk about the boys wanting to educate themselves, and you know, thinking about going to the university, going to college," Murillo said.

One of her cousins, Bennie Lopez, used the G.I. Bill to go to college.

She said her brothers and cousins fought alongside Anglo soldiers and that might have influenced their attitudes. She remembers when her brother, Edward M. Olvera, said of Anglos: "They are not better than us, we are the same."

When her brother Edward returned from the Pacific, he got sick and went to a Veteran's hospital, but sometimes they wouldn't help.

"He fought for his rights. He would write and talk to senators and tell them that he had served his country and now it was time that his country helped him," she said.

After the war, her father, uncle and other relatives joined the League of United Latin American citizens (LULAC), Woodmen of the World and other organizations that work for positive social and economic changes for U.S. Latinos.

The Hispanic community from South Austin would meet at a hall located at 1300 S. 1st St. and plan how they could improve their neighborhood, she said.

"We would go house by house and we would talk to the people. We wanted to get them to vote, that's the only way we can be heard," Murillo said.

They also urged people to get educated, and many years later, they organized a night school.

"That's how I finally got my GED when I was more than 50 years old," she said, adding that she’s happy to see the situation has improved for Latinos in the U.S.

"They have more opportunities and I think they want to do better,” she said.

When Murillo tells her grandchildren about segregation, they find it hard to believe.

"They are just grateful for being able to get along with everybody," she said. "They find it strange sometimes if we tell them some of the things that we had to go through."

Mrs. Murillo was interviewed in Austin, Texas, on October 15, 1999, by Ana Acosta.