By Kayla Young

Peering through the door he’d just kicked in with his combat boots, the Manuel Camarillo serving on the front lines of World War II Germany was a different man from the one he’d been back in South El Paso. Back then, he’d started fights just for fun.

“I spent my time fighting. I wanted to fight anybody,” said Camarillo of his early teen years. “My oldest brother would get two or three guys in the morning. He would get them so I could fight with them. I went in [the alley] and I gave them a good whipping.”

In his Bowie High School yearbook, “The Growler,” Camarillo is described as a “bad humor man,” as well as in the following terms:

He is a radical in every meaning of the word. He likes no subjects, belongs to no clubs, has no hobby, is not going to college, has no plans for work, likes nothing and dislikes nothing.

But through his experiences in the Army, Camarillo came to realize the preciousness of life and developed a sense of empathy, not only for the enemy soldiers, but the civilians caught up in the fight.

After kicking in the door of a German house he’d been certain hid something suspicious, the young gunner for the 90th Infantry Division, standing before a terrified family rather than enemy soldiers, felt a weight on his heart that would remain with him throughout his life.

“There was a little girl and two little boys sitting down at a table,” he recalled. “That has stayed on my mind forever and it will stay there. It was just like a movie. All of them had a little plate and they had a little piece [of bread] in there with water and nothing else, and they were gonna eat.”

The scene brought Camarillo to face a human element of the war he hadn’t previously considered.

“When you’re there – 18, 19 years old – you just shoot at anybody. You don’t care,” he said. “I never thought about it there. I didn’t have time to think. Because that guy had a mother, he had a father, he had a sister, he had a brother and kids and all that.”

Moved by the destitution of the family, he rummaged through his pack and without a word removed all of his food rations and cigarettes, currency more valuable than money. He placed the items on their table and left.

“I bet they were real happy. I had broke the door down,” he said with a chuckle, many years later.

But for his greatest acts of selflessness and compassion, Camarillo received no praise.

In another instance, a fellow United States soldier went missing beneath the current of the Rhine River and a soldier from the man’s unit ran and asked Camarillo to help locate the body. Exhausted from searching and the force of the undercurrent, Camarillo finally stumbled across the foot of the soldier and, after some struggle, pulled him out – a young African American man whom he’d never even met.

Rather than praise him for his act of bravery toward a fellow American, his captain berated Camarillo for his actions.

“Why in the hell did you get him out? Why didn’t you let him drown?” Camarillo recalled the captain having screamed at him the next morning.

“It didn’t matter [to me] that he was African American, it only mattered that he needed to be saved,” wrote Camarillo after his interview.

And when medical treatment couldn’t save the young man’s life, Camarillo’s captain made a point of expressing his satisfaction that the “n--” had died. In the face of disrespect and often blatant racism, Camarillo kept up his efforts, however.

Looking back at the terrors of Normandy on D-Day, he says he and his unit didn’t “gripe,” despite the feeling they were “little league boys playing the New York Yankees.”

They fought hard because they believed in their effort, Camarillo says.

Camarillo was also among the liberators of the Buchenwald concentration camp. When he and his unit arrived at the camp, they discovered the German occupiers had abandoned the area in a hurry.

“Even where they burned the bodies, they were still going. Even the tractors were running by themselves. They were not expecting anything, I guess,” Camarillo said. “And they just left [the prisoners] there to die. They didn’t do anything with a bullet or anything. They didn’t want to waste a bullet.”

“Lots of them were already dead. Rows and rows of bodies,” he added in writing.

At one point during his three years in the service, Camarillo was issued a shoe size far too narrow for his foot. On long hikes, his feet would crack open and drench his socks in so much blood he would have to wring them out. But once his sore feet had taken him to his intended destination, Camarillo wouldn’t focus on the pain, but on two things not expected of him: learning some of the local language and getting a girlfriend.

“You learn a language better with a girlfriend. If we went to a town, the first thing to do is I get me a girlfriend.” he said. “I wanted to talk French and learn the language and all that. I’d start talking to them a little bit and then they’d start talking to me and we’ve got it made.”

Back in school, Camarillo had been labeled as a student who took no interest in his schoolwork, but in the middle of war, he absorbed information like a sponge: Of the 125 Mexican Americans who comprised his unit, Camarillo says he was the only one who left knowing more than three or four words of another language. He picked up a good bit of French and German during his tours simply by conversing with people on the street and, of course, with his many girlfriends.

“I never wanted to learn languages through the book,” he said.

Once settled back in the U.S., the formal education Camarillo had struggled with would become a priority in his family. He committed himself to his work at the Zork Hardware store, the place he’d been employed with before the war, so his five children could have the option to attend college. Camarillo would stay with Zork for 45 years.

“Education is number one, and I know because I don’t have the education,” he said. “But my kids are going to have what I didn’t have.”

In Camarillo’s home growing up, the importance of hard work and responsible spending came first.

His mother and father relocated the family to El Paso from Aguascalientes, Mexico, in the 1920s, and through their hard work, lived by example for their children.

In his job as a candy seller, Camarillo’s father, Jesus, would bring the children along on the early morning sales to stores around the area.

“It was hard work and all of us helped,” Camarillo said.

And when the money came in from their work, the Camarillo children were taught to handle it responsibly. All of the children were given personal banks to store their change in as it came along.

“Everybody in my house was a saver” Camarillo said. “We never took out money. We just saved it.”

And when it came to the choice between higher education and continuing work, all 10 of the Camarillo children chose work.

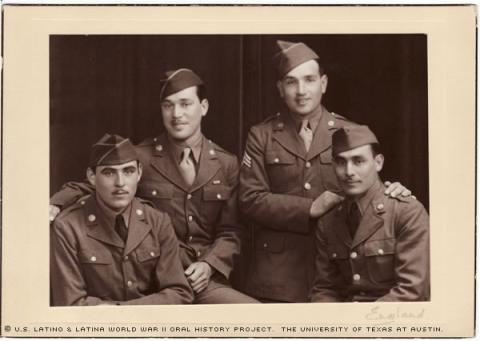

Like Camarillo, all of his brothers chose to serve in the military and fight on the frontlines.

“All the five left the house the same day and all of them stayed for about 3 years,” he said.

Camarillo recalls his mother, Fermina Corpus, had dark hair when the boys left for war and was already gray when they returned. The departure of all five brothers at once would always bother him.

Camarillo’s children would lead different lives from him and his siblings, however.

Of his five children, all “brilliant,” he claims, four have received bachelor’s degrees. They now enjoy careers in fields like mechanical engineering and administration – a sharp contrast to that young, uneducated couple from Aguascalientes with nothing but their determination to build a new life for their children.

Mr. Camarillo was interviewed in El Paso, Texas, on September 1, 2007, by Raquel C. Garza.