By Pierre Bertrand

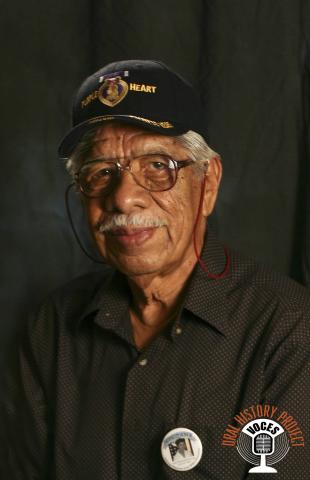

It seems as if Army infantryman Julian Medina, who was drafted in 1943, was on the frontlines of every major World War II European campaign, from the Normandy Invasion to the Battle of the Bulge.

“I was in every fight. I was in every battle,” said Medina, who was part of the Army’s 119th Infantry Regiment, 30th Infantry Division in 1943.

His European service began in Scotland, where he was among thousands of American soldiers being trained for amphibious assaults.

According to military histories at the National Archives and Records Administration, the division entered France on June 10, 1944, four days after the start of the Normandy Invasion, to participate in the assault on St. Lo in Normandy. German troops retaliated on Aug. 30, and the division was engaged in heavy fighting for a week before the Germans were pushed back.

By December, Medina was fighting in the Battle of the Bulge, along with about 500,000 other Americans.

In the preface to “Nuts: The Battle of the Bulge,” authors Donald M. Goldstein, Katherine V. Dillon and J. Michael Wenger, describe the battle as “a patchwork quilt – a multitude of small engagements played out in or near small towns, most of no military significance.” Nonetheless, the U.S. suffered approximately 81,000 casualties, including 19,000 killed; The British suffered around 1,400 casualties, including 200 killed. Germany lost an estimated 100,000 -- dead, wounded and captured.

Medina recalled fighting alongside other Latinos while stationed at an outpost on the frontlines in Normandy. He also recalled composing letters for one of his illiterate companions, who was writing to two separate women. Each letter mentioned the soldier’s intent to marry the woman upon his return.

“I said, ‘No, you can’t do that,’ ” Medina said with a laugh. “He said, ‘We are all going to get killed. I want to make them happy.’ ”

On Christmas Day 1944, sheltered in a foxhole, Medina said he spotted a chicken pecking at the ground. After shooting and cleaning the bird, Medina said he roasted it; he was the only soldier in his squad to do so.

On another occasion, Medina and another soldier were looking for enemy troops. Medina recalled that German troops approached their position one day, and he and the other soldier had to fend them off using hand grenades. His fellow soldier kept his boots off in an attempt to get frostbite so he could be transferred home and discharged.

“I have a lot of happy memories and a lot of sad memories, too. That’s what keeps me going, the happy memories,” Medina said. “One of these days, when I am gone, it will all be forgotten.”

By March 1945, the 30th Infantry crossed the Rhine River into German territory. It was during this campaign that Medina was wounded and left, he says, behind enemy lines while others withdrew. Medina recalled being with another soldier, also wounded, who was crying for his mother. Medina said that he and the other soldier were eventually rescued four miles inside German territory.

When making his way back across the Rhine, Medina met and had his hands shaken by a man Medina said he did not know.

“He shook my hands and said, ‘Good show, good show,’” Medina said. “People looked at me and asked if I knew who that was. They said it was Winston Churchill. I don’t know if it’s true, but that’s what they said.”

To recover from his injuries, Medina was sent to a hospital not far from Paris toward the end of the campaign in Europe.

With the closure of the European Theater, troops were being shifted toward the Pacific. But the war ended before Medina got there.

“When the atomic bombs exploded in Japan, we were halfway across the ocean. When the bombs exploded, that’s when we went home,” Medina said. “That’s what the atomic bomb did for me.”

Home for Medina was San Antonio, where his family’s roots dated back to the early 1900s, when his father, Francisco Medina, entered the country to escape poverty and the chaos of the Mexican Revolution. In San Antonio, Francisco met his future wife, Florentina Montoya, who was also from Mexico.

Medina was the oldest of nine siblings. He had three sisters and two brothers, all of whom died at early ages in the 1920s. As a child, he worked as a carpenter in his father’s guitar shop, and attended school for seven years.

He recalled the family’s struggles in the 1930s.

“Times, they were hard, because it was during the Depression,” Medina said. “There were no jobs. Of course, you get used to it. My mother always said you can get used to anything except not eating.”

Medina remembered how in December 1941 he was leaving a movie theatre when he first saw the newspaper headlines about the attack on Pearl Harbor, and the subsequent indignation felt by the entire nation. As a 16-year old, however, he says he was not concerned and did not anticipate receiving draft papers a few years later, in 1943.

“When I was drafted, I felt nothing,” Medina said. “You see, that time was different. Now you have a long history, and you feel like you have a choice to serve your country. At that time, it was your obligation. I said, ‘My country needs me, how can I help you?’ ”

After the war Medina, was hired at a lumberyard and worked as a carpenter for decades. In 1947, he married Marcelina. They had three boys and four girls.

Medina said he was wounded five times during his military career and entered behind enemy lines three times. For his service, he earned two Purple Hearts, a Campaign Star, Combat Infantryman Badge and Good Conduct Medal, among other honors.

Medina said the war had a major impact on him.

“I get nervous sometimes,” he said. “At night, I wake up. I blame it on the weather. Lately, it hasn’t been good, so every time I think about it, I dream about it. I don’t think I’ll ever forget it.”

Medina says he learned the hard way not to get attached to the soldiers he fought with.

“I’ve got many things that would take me a whole lot of time to tell you,” Medina said. “I don’t remember the names. I recall the eyes. People died every day, hundreds and hundreds. I learned not to make good friendships. I know what I did. If you believe me, that’s OK. If you don’t, that’s OK, too.”

(Mr. Medina was interviewed on Aug. 4, 2007, in San Antonio by Jenny Achilles.)