By Maggie Rivas-Rodriguez

Every year at Christmas, José Borja organizes a celebration at a nearby Veterans Administration Hospital, in particular to honor aging Merchant Marines.

The cause of recognizing the Merchant Marines has become Borja's life's work. He has founded an organization called Association of Merchant Marine Veterans. He has written countless letters to public officials and others. He has called and spoken to any group and journalist who might listen. He has written newspaper columns emphasizing the wartime contributions of the Merchant Marines.

"At the end of the Second World War, the problems for the Merchant Marines began," Borja said.

About 125,000 U.S. Merchant Marines served in WWII, according to court documents from a lawsuit filed in connection with a Merchant Marine claim. Court documents note that 5,662 Merchant Marines either lost their lives or were declared missing during WWII. Another 609 became prisoners of war.

After WWII, Merchant Marines were deemed ineligible for veterans' benefits, including educational help and mortgage loans.

Borja maintains that the Merchant Marines were told that, since many were not U.S. citizens, they would not be regarded as U.S. veterans. "Of 120,000, I would say about 70 percent were illegal."

The U.S. Merchant Marines have a long history of fighting for veteran status. The government for several years argued that, because Merchant Marines could resign at any time - unlike active military - and for other reasons, they should not receive veterans' benefits.

Several lawsuits have been filed in connection with WWII-era Merchant Marine claims, including one by Stanley Willner, whose ship, Myakola, was struck by a German torpedo in the Atlantic in November 1942. The Germans transferred him to Singapore and handed him over to the Japanese.

Willner spent three years as a Japanese POW. He was part of the prisoner group that built the bridge over the River Kwai, which became the title of a movie about the exploits of those prisoners. When Willner came back to the States after the war, he was denied veterans' benefits.

Willner eventually sued the government, contending that it had arbitrarily denied the Merchant Marines veterans status and benefits while providing them for civilians including telephone operators. In 1988, a U.S. District Court judge for the District of Columbia ruled in Willner's favor.

"The injustice endured by Merchant Marine veterans is both cruel and shameful," Borja wrote in one newspaper column for Hospitalized Veterans Writing Project Inc. "Those who served suffered such devastating effects, yet they have never been honored nor assisted as others who served in war."

There should be a monument in their honor, Borja says, and it should be in New York, the location of the National Maritime Union. An amateur artist (several of his paintings hang in his home, he has drawn a sketch of what that monument should look like. He has copyrighted that sketch.

Borja was born in Quito, Ecuador, on April 3, 1927, and went as far as sixth grade at a Catholic school called Cebollar Colegio de Curas. He was the oldest of five children born to Juan Bolañoz - who worked as a bricklayer/carpenter/electrician - and Rosa Borja.

He ran away from his home in 1942 and lived in Colombia for a year before stowing aboard a French ship. French officers took pity on him and allowed him to serve as a steward aboard the Athos2, which carried between 8,000 and 10,000 men, a full division.

The officers cleaned up the skinny teenager, told him which paperwork he needed from which government office (immigration, the head of the port, the sanitation department and the police department) and gave him new clothes - including a huge pair of boots twice the size of his feet.

"Two of my feet would fit into one boot," he said, demonstrating with his hands his slender feet and the large boots. "But they were new.

"Since that time, I was no longer poor," Borja said. "A star was born for me," he said, signaling with an index finger toward the heavens. "From that day, I began to educate myself, live in a different world ... I would travel the world, I have worked with the richest men, I have lived in the best hotels, I have eaten with important people."

His job was to fill bottles of wine from a giant cask for the French officers aboard the ship - two bottles daily for each officer; American officers who came aboard to dine got one bottle. He earned $75 a week in tips, he said.

"The French, if they don't drink wine, they can't eat. The food won't go down," he said. "They don't want anything to do with water."

In 1944, after docking in New York harbor, he joined the National Maritime Union, and, through the union, the U.S. Merchant Marines. A friend, Oscar Bello, of Peru, urged him to do so, telling him he could earn higher wages and have greater benefits and job security that way.

"He said, 'José ... I am leaving this ship, I am going to join the union. I will work on an American ship. They will pay me a good salary, and I will live 20 times better. Why don't you do the same?'" Borja recalled.

Borja did so and was assigned to several different ships that traveled throughout the world.

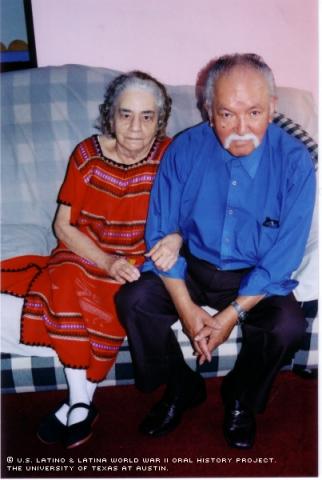

In 1946, Borja married Stella Carattini, a Puerto Rican. During the war, she worked in a wool factory in Manhattan, mostly with Italian girls, and earned $18 a week.

"That was so easy," she said. "You would take the wool and wind it around and around."

Her boss, Mr. Weinberg, was Jewish and observed the Friday Seder, but in busy times, he needed the crew to work weekends.

"He paid us double and would buy us lunch," she recalled. "He was a nice man."

The couple settled in the Bronx and started a family. They eventually had two sons, Ronald and George, and one daughter, Rosita.

Over the years, Borja brought his siblings and his mother to live in the Bronx as well.

After serving, he settled in the Bronx and worked at various times as a bellboy, a bartender and a waiter at fine restaurants, including the Tavern on the Green.

He also has self-published several books, mostly fiction, including one in 1982 that seemed to presage the World Trade Center attack in 2001. But in his fantasy, Borja had explosives in the center of the building. He said he has no idea how he gets his ideas for his books: They just come to him.

Borja also continues to champion the cause of a monument in honor of the U.S. Merchant Marines who served in WWII. Although most were awarded benefits in 1988, it was too little, too late, he said.

"You can be certain that we're not going to find a Merchant Marine lawyer," he said. "And I am sure that you're not going to find a doctor or surgeon Merchant Marine. ... In those times, you had to have money to study. How is the GI Bill going to help me?''

Mr. Borja was interviewed in Bronx, New York, on April 24, 2004, by Maggie Rivas-Rodriguez.