By Adam Keyrouze

Both his father and his grandfather had served their country proudly during World War I and World War II, respectively. So José Antonio “Tony” Dodier didn't think twice about joining the Army.

Dodier’s first military training came when he was a student at Texas A&M University. A few years later, he was a young Army officer in the jungles of Vietnam, in a war he did not understand but which would leave him wounded, physically and emotionally.

Dodier was born and grew up in Laredo, Texas, but he spent many weekends and summers on the family ranch near Zapata, about 60 miles away, learning to ride, rope cattle, and hunt rabbits and javelinas.

It’s a 20-minute drive from the first gate to the house, where one wall is filled with photos and mementos from Dodier’s military service, and his father’s and his grandfather’s service.

His father was determined that all three of his sons – Tony is the oldest -- would go to college. “Since growing up, all I ever heard was that I needed to go to college and that I should consider Texas A&M. So I only applied to A&M,” Dodier said. “I just knew it was what my grandfather and father had wished for me.”

He didn’t know that the school was a military training institution as well as a civilian university and that students were required to sign up for the Corps of Cadets and participate in the Reserve Officer Training Corps.

Dodier signed up for the Army program as a freshman. While juniors and seniors did not have to participate, he stuck it out all four years.

Dodier was not a typical student: He had married Lucila Zuñiga shortly after high school, and the couple would have three children – Marta Cristina, José Henry and Cordelia Michelle -- by the time he graduated from A&M in 1969. Corps duty paid $50 a month, covering their rent.

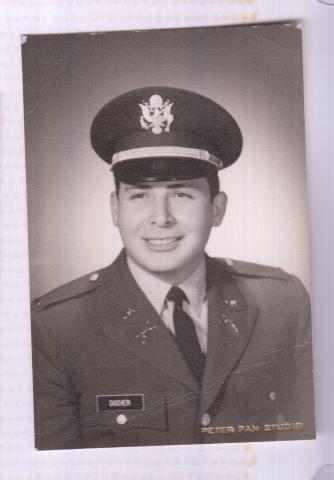

After earning a degree in industrial distribution, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant and received training at Fort Benning in Georgia and Fort Sam Houston in Texas. In January 1970, he went to Fort Sheridan in Panama for jungle survival and combat training. The next month, he was in Vietnam. He was a 21-year-old platoon leader in the 198th Brigade of the 23rd Infantry Division.

“The thing I remember about Vietnam was a lot of uncertainty and confusion,” he said. “At times, we questioned what we were doing. The code for the platoon was, ‘We are going to get each other through this. We are here to take care of each other; we will look out after each other.’”

Conditions were tough; soldiers carried 60-pound backpacks and slept in shallow holes in the ground, with no tents. Despite the constant rains, they didn’t wear their waterproof ponchos because they were noisy and might alert the enemy to their location.

Dodier said he received occasional mail from home, including care packages with dried meat and cans of menudo – spicy tripe soup.

Dodier put a positive spin on things in letters to his mother and wife. But he was candid with his father, confiding his concerns about “disorganization and a lack of caring or understanding from the higher command.” He also told him about the day he had tripped three booby-trapped mines, none of which exploded.

His father advised him to “move carefully, like stalking a deer,” and to rely on his men.

Dodier asked to take a break from the interview before he talked about the explosion that maimed him.

It was May 28, 1970, and his platoon was one of three assigned to search and clear areas abandoned by the Viet Cong. A “Kit Carson Scout,” the name for former Viet Cong now helping the U.S. military, warned Dodier that the area was “heavily mined and booby-trapped. I immediately relayed that to the company commander, but he did not want to listen. ‘You have your orders. Go ahead.’”

Dodier said he did not want to put his men at risk, so the platoon stopped and set up a perimeter at the village they were set to clear. They heard an explosion nearby: Another platoon had hit something, and the men were calling for help. A mortar squad had set off a mine, wounding 10 of the 11 men in that unit. The only one uninjured was the medic, Dodier said.

“We got there, started requesting medevac (helicopters), and they loaded up the wounded,” he recalled. “I told them, ‘They hit the booby trap right there.’ And as I took a step, the explosion just kind of temporarily blinded me with the smoke and the dust.”

Dodier had stepped on another mine – the first member of his platoon to be injured.

“McNichols [one of the sergeants] started yelling, 'What happened?! What happened?!’ And I just looked down and said, ‘I blew my foot off.’ I had stepped on what was called a toe-popper.

“I started yelling to the platoon that we were in a minefield and not to move. … Another soldier knocked me down and started treating me. McNichols requested a medevac, and I told him: ‘Make sure the copter pilot knows we are in a minefield.’”

Another copter arrived with battalion commander Lt. Col. Norman Schwarzkopf and a captain. Schwarzkopf and the captain jumped out of one side, while Armando “Tiny” Monterubbio threw Dodier into the helicopter from the other side. As the chopper rose in the sky, another explosion went off, injuring the colonel and the captain and killing Monterubbio.

The day’s toll: 28 wounded and three dead.

Dodier was taken to the military hospital at Cam Ranh Bay, then to Japan for surgery and finally to Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio. There, doctors told him that they had to amputate his right foot, because the tendons that allowed him to lift it were gone.

A captain at the time of his discharge, Dodier returned to Texas A&M to earn a master’s degree in education and then went back home to Laredo, where he got a job at Laredo Junior College (now Laredo Community College), helping veterans with GI Bill and other benefits. He later worked to expand access to federal grants and work-study programs so more students could afford college.

But he wasn’t the old, easygoing Tony. He noticed a change in himself.

“I became very quick-tempered after I came back and could never understand why. Especially when people don’t listen to what I say.”

He would get angry even with his own family.

At the time, no one had heard of post-traumatic stress disorder, and Dodier didn’t seek counseling for his short temper. Years later, he went to anger management counseling after he became physically violent with someone.

“I learned to walk away” when he became angry, he said.

As he began to understand what led to his impatience, it made more sense. The memory of that day in Vietnam remained painful, even 45 years later.

“About 10 years ago, a Veterans Administration counselor told me, ‘What your mind remembers is that when people don’t listen to you, bad things happen.’”

Dodier doesn’t think there were any consequences for the commander who ignored his warning about the mines.

“I doubt anything happened to the commander… he was a West Point graduate,” Dodier said.

Dodier was awarded a Bronze Star for valor and a Purple Heart, but he wanted only a small private ceremony and no publicity.

“The nation as a whole was so much against the Vietnam War, and veterans were considered baby-killers,” he said.

“Kent State happened while we were in service,” he said, referring to the Ohio university where National Guard soldiers shot and killed four student anti-war protesters on May 4, 1970. “I remember not understanding why people were protesting.”

He did not encounter many protests himself because he lived on the post. But he said, “We were advised not to travel in uniform.”

After helping veterans at Laredo Junior College (now Laredo Community College) and working to expand access to education grants and work-study programs, he spent more than a decade as a banker in Zapata.

In 1989, he returned to the ranch, where he runs a cattle operation.

“I enjoyed what I was doing,” he said. “Why look for anything else?”

In 1990, he and Lucila divorced; eight years later, he married Sylvia de Anda.

Their home sits on a high spot on the land. On one wall hang framed rubbings of three names from the Vietnam Memorial -- the three men who were killed that day in 1970. The rubbings were made by Dodier’s longtime friend, Jorge Haynes.

Dodier’s voice grew hoarse as he read their names: “Dennis, he was from Chicago, a private. … Anton, he had a wife and daughter. Armando, he was single.”

Dodier said he is proud of the fact that none of his men died while he was in charge, but the toll from that day still weighs heavily on him.

“We promised to get each other through,” he said. “I promised.”

Mr. Dodier was interviewed by Maggie Rivas-Rodriguez on Aug. 1, 2015, in Zapata, Texas.