By Bianca Krause

Dec. 8, 1941, forever changed his life.

Riding in a car on Market Street in Laredo, Texas, 16-year-old John Valls heard a speech that would shape his future. With his “Day of Infamy” speech, President Franklin Roosevelt declared war on Japan after the Pearl Harbor attacks and convinced Valls that his life’s mission was to serve his country.

The Laredo native then walked to Fort McIntosh in Laredo to enlist in the Army but was told he was too young. “I knew I wanted to fight, but I was just a kid,” Valls said. “I was so disappointed when they kicked me out. I wanted to defend my country.”

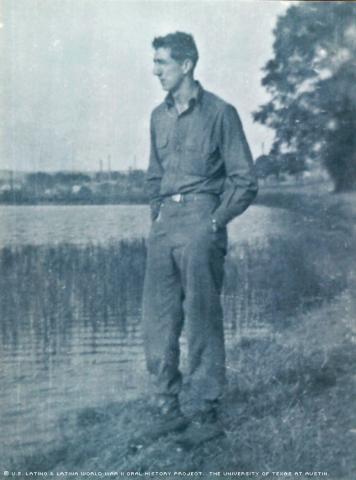

Two years later in 1943, he was drafted at the age of 18. Valls served in the 52nd Armored Infantry Battalion. “I was so happy to get in there,” Valls said. “I was going to get to fight.”

“The first [German] soldier I ever met should have killed me,” Valls said. “I was a rookie, and I had him point-blank, but I froze. I couldn’t kill him.”

After the soldier put down his gun to surrender, Valls told his sergeant he caught a German soldier but was unable to shoot him. “All he told me was, ‘Don’t worry, son, next time you won’t …’ ” Valls said. “And he was right. From then on, it was hell.”

Valls remembers digging holes to sleep in every night and surviving on a few packets of food every day. “Every day you were cold, you were hungry, and you were scared,” Valls said. “It’s not like John Wayne in the movies. It’s hell.”

Valls admitted he robbed German soldiers at gunpoint, stealing knives and watches that he brought back home to his family and friends. “To this day it haunts me,” Valls said. “I knew it was wrong, and I’m ashamed, but I did it to many soldiers.”

Valls attended class 44C pilot training at Stevens Point, Wis., but the class was eliminated because there were too many pilots. Then he was shipped to Southampton, England, for advanced infantry training.

In 1943, after he shipped out to Bolton, England, Valls was stationed at Base Air Depot No. 2. He spent his free Sundays running on a track nearby. A royal official discovered his talent for running and jumping hurdles. The base commander sent Valls to compete in several competitions, including one attended by Queen Elizabeth, mother of Queen Elizabeth II. He won first place in the 400-meter hurdles at that meet.

“The queen came out, and it was just electric,” Valls said. “The English subjects started to bow, and I did too. Everyone acted like a god had just come out.”

Valls was given a certificate in lieu of a medal because of the scarcity of silver during the war. In 1996, Valls contacted London officials regarding his award, and he was finally sent a medal.

Valls had five brothers and four sisters. Two of Valls’ brothers served in the Air Force during World War II. One brother, 1st Lt. Louis Valls, a B-26 pilot, was killed in Italy during his 27th combat mission. Another brother, 1st Lt. Alfonso Valls, flew 30 missions from Guam to Japan as the pilot of a B-29.

Pfc. John Valls was discharged on Feb. 26, 1946, at Fort Dix, N.J. In November, he married Gladys in Laredo, and they eventually had five children.

Valls attended Baylor University, ran track, and served as track captain during his senior year. “My life was sports. All my brothers were super athletes, and I had to be a super athlete too,” Valls said. “I never failed any subject in school, but I wasn’t a student. I was an athlete.” He graduated in 1950 with a bachelor’s in business administration.

Valls grew up on a Laredo ranch, where his family grew Bermuda onions and tomatoes on more than 10,000 acres. His father’s ranch allowed the family a privileged lifestyle during the 1930s and much of the Great Depression. He and each of his siblings had nannies to look after them, while their cook, dishwasher and two maids took care of the home.

“It was feast or famine in those days,” Valls said. “People, white people, would come begging us for food. I couldn’t understand why some kids didn’t have food but we did. I was a kid and didn’t understand the Depression.” He wouldn’t until 1939, when onion and tomato prices fell and the family lost the farm.

Valls remembers his mother, Rafaela Mendiola, who died in 1941 of pancreatic cancer, setting up tables on the back porch of their house for hungry travelers to stop for a meal as they made their way to California from the Midwest.

More than 70 years after the war, Valls said he still experienced headaches and nightmares about his days as a soldier. After he was discharged, Valls was diagnosed with what is now known as post-traumatic stress disorder and is considered a disabled veteran.

"The thing that bothers me most is that I killed people. They're not coming home, but I'm home," Valls said. "They're dead because of me."

“I’d have these awful headaches and lose my peripheral vision,” Valls said. “I dreamt I was in my own funeral procession.”

Mr. Valls was interviewed on March 6, 2010, by Liliana Rodriguez in Laredo, Texas.