By Rachel Fleischman

Before he was 20 years old, Joel C. Mojica had fought in one of the bloodiest battles of World War II, and had a Purple Heart medal to prove it.

Mojica was an Army sergeant during the war, and, like many young men of his generation, was drafted when he was only 18 years old. After he was called up on Oct. 29, 1943, Mojica was sent to Hampton, England, where he trained for battle on a daily basis. His role in the Army was as a replacement soldier; his unit sent personnel to companies needing men to take the place of wounded and dead soldiers.

Mojica’s job as a replacement led him to the beaches of Normandy, France, after D-Day. During the Normandy invasion, he was initially in England with his unit, the 79th Infantry Division of the 14th Battalion, but quickly received orders to cross the English Channel and reinforce the dwindling troops at Normandy.

On June 10 1944, four days after D-Day, Mojica arrived in France to bear witness to an awful sight: Dead bodies of the men who hadn’t made it to shore were floating in the water; they were the men he’d been sent to replace.

Mojica says he was frightened at the thought of fighting, but seeing the dead bodies of his fellow soldiers made him angry.

“I had to do something so that others won’t be killed,” Mojica said.

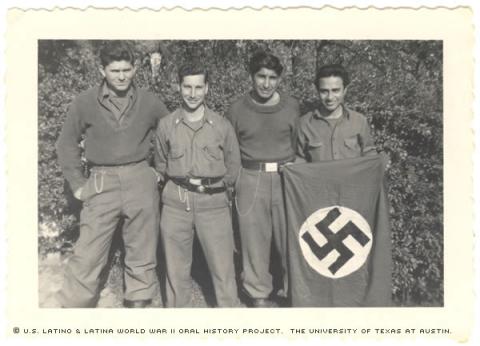

After fighting on the beaches at Normandy, he traveled through France battling the Germans. In a small town in northern France, Mojica went on a scouting mission with four other GIs: He was to find out the positions of the enemy’s guns in the area and radio them back to command.

The five men came under fire. After Mojica scouted all the guns, he recalls trying to signal the other GIs to run, then realizing they’d all been killed. Unaware of the bullet in his knee, Mojica sprinted back to his unit. When he was safe, he remembers feeling blood run down his leg and realizing he was wounded.

During wartime, a bullet in the leg is looked on as one of the less serious wounds, so Mojica was patched up by medics and sent right back to the front line. H received the Purple Heart for his injury in the scouting mission, as well as an Oak Leaf Cluster, for when he was hit in the shoulder by shrapnel from an artillery shell during another battle in France. (He didn’t receive multiple Purple Hearts for his multiple wounds because in the U.S. military, soldiers typically only earn one Purple Heart; subsequent wounds usually earn an Oak Leaf Cluster.)

After his Dec. 31, 1945, discharge Sergeant Mojica returned to his hometown of Uvalde, Texas, 85 miles west of San Antonio, and came back to the family who’d sent him care packages of cookies, news from town and updates of how his childhood friends were faring in the war. For Mojica, Uvalde held memories of cowboys on cattle drives through town; the Diez y Seis de Septiembre celebration, where his mother would sell homemade snow cones, tamales and enchiladas; and neighbors who’d lend a cup of sugar whenever needed.

Mojica grew up comfortably in Uvalde; his father, Miguel Mojica, had steady work as a carpenter, making $12 for a six-day week. Later, Miguel became a lay pastor for the Primera Iglesia Bautista de Uvalde. As a child, Mojica helped his father after school, and when Mojica left school in the eighth grade, he went to work as a carpenter with his dad full time.

Mojica says his trade taught him to take care of his tools, a lesson that would come in handy during the war.

“In construction you have to keep your tools sharp and clean, and in the Army you have to keep your rife clean,” he said.

Mojica says he saw many a man who didn’t clean his gun have it fail on him when he most needed it. He recalls cleaning his religiously, becoming so familiar with his firearm he could disassemble and reassemble it in the dark.

Mojica also contributed to his family by raising pigeons and chickens to sell to his neighbors in Uvalde. At one time, he says he had more than one hundred chickens. Among other orders, he recalls selling young pigeons to sick neighbors who believed soup made with them could help heal a cold.

His mother, Paz Castillo Mojica, was a resourceful woman, who Mojica says made him wonder how she put so much food for her seven children on the table while on such a small budget.

“She was a very busy person with the kitchen, and we were well fed,” he recalled.

Members of Mojica’s family worked together to support each other when he was growing up. For example, his grandfather grew corn his mother would cook and grind for tortillas; he also was a woodchopper, providing fuel for cooking and heating.

After WWII, Mojica went back to work as a carpenter with his father, eventually getting a job building cabinets in a cabinet shop. Wizened by the war, he had trouble accepting Uvalde’s discrimination against Latinos. For example, many eateries refused to serve Hispanics, and the ones who did, had a separate area for them to sit, he recalls.

“It was very disillusioning that I went and fought for liberty,” Mojica said. “But at the same time, I didn’t have the liberty to go into a restaurant where Anglos were eating.”

Mojica says he’s happy with the changes the country has gone through over the years. His children and grandchildren now have opportunities he never had, and they may go any place they please.

“They’re accepted now, anywhere,” Mojica said.

Mr. Mojica was interviewed in Austin, Texas, on July 5, 2007, by Jesse Herrera.