By Kristina Radke

Before World War II, Jesse Nava led a simple life in California, swimming in the Los Angeles River and gaining a strong work ethic from his immigrant father. But since the war, that carefree life has been elusive.

To help his father support the family, Nava was forced at age 17 to drop out of the predominantly Latino Roosevelt High School, where he was successful in breaking track and field records. In addition to his parents, Nava's family consisted of two brothers and two sisters.

"My father always said, 'Do the best you can,'" Nava said. "'If you do your best, you'll always have a job.'"

Nava strove to be independent even as a teenager, working hard for the railroad and staying away from home as much as possible.

"If I wasn't around, they didn't have to feed me," he said.

The war began before Nava left high school, but he didn't feel its effects until he turned 18.

"When you're not involved, it's just a war," he said.

As his friends became eligible for the draft and were called up, Nava says he longed to join them. His social circle became increasingly smaller, and he wanted the opportunity to see the world.

So when he turned 18, on June 30, 1943, he registered for the draft. Seven days later, he was sent to Fort McArthur in San Pedro, Calif., to prepare for basic training.

"Mom [Francis D. Nava] felt bad," Nava said, "but the others were proud ... Dad said if your country called, you go."

Nava's father, Cacimiro Nava, was born and raised in Mexico, but felt an obligation to the United States because he’d availed himself of opportunities that had eluded him in his native land.

Nava spent much of his time at Fort McArthur peeling potatoes on Kitchen Police, or KP, duty, which was punishment for having exceeded his day passes.

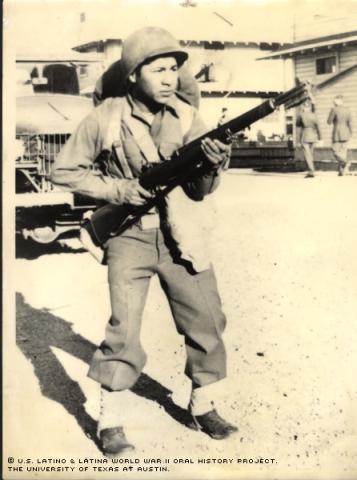

Nava was then sent to Camp Roberts for basic training, where he was assigned to a heavy-weapons company. When he was told he’d have to carry a heavy base plate and mortar rounds, however, he took the initiative of transferring himself to a different company.

During the night, he snuck into the barracks of the 77th Training Battalion and went to roll call with them the next morning. When his name wasn’t called, he explained he was new. He further offered that, somehow, his records must have been transferred to the 77th Battalion.

The ploy worked, and he was allowed to remain a part of the infantry, becoming a member of the 24th Infantry Division, 21st Regiment, C Company.

Nava didn’t notice many other Mexican Americans during the war; there weren’t training officers, no sergeants and no corporals when he started, he says, adding, however, "To me, it didn't make any difference. … If you're an American, you're an American to me."

When Nava arrived in New Guinea in May of 1944, he began patrols of the surrounding forest. "You never know who's there, who's looking," he recalled. "The trees were so tall and the bushes were so dense ... Fireflies sometimes look like wristwatches moving ... a night was like a year."

While in New Guinea, he contracted malaria but was never taken to a hospital. The supply boat that had just arrived on the island broke down, and they were unable to communicate with anyone, including medical personnel, until the ship was running again. Nava rested in his bunk for the seven days it took the boat to be repaired, and was up and walking around when it was finally fixed. He’d recovered from malaria on his own, and wasn’t in need of medical attention, he says.

Nava’s first taste of combat took place in New Guinea when a group of natives told his troop that some Japanese were coming down the trail. The Americans set up an ambush and killed the enemy forces.

Nava soon began collecting the gold and silver teeth among the enemy casualties as good luck charms, even giving them as gifts to his hospitalized comrades, he says. In retrospect, Nava says the horrific backdrop of war helped him rationalize the macabre nature of the collection.

"You're not human no more," he said. "I was enjoying myself. It's like picking a ripe orange."

The realities of war also helped him justify having to kill.

"If they're the enemy, you kill them," he said. "There's no difference in killing a child, a woman, a grandma, a grandpa, whoever. There's no remorse about killing anybody because it's your job."

After New Guinea, he was sent to the Philippines, where he felt what it was like to be on the receiving end of violence when he was separated from his troop and captured by some Japanese. He was immediately attacked upon surrendering his weapon, struck in the face and in the ankle with bayonets and hit in the back of the head.

As a result of those injuries, Nava says he lost the ability to write and spell, though he can speak and read with ease. The beatings eventually stopped, a development he attributes to the arrival of a Japanese officer who may have asked his soldiers to cease. To his amazement, the Japanese troop left him alive. His own troops found him soon after and couldn't believe he’d been spared.

Until a recent interview, Nava never told his wife or children the harrowing account of his survival. His wife, Magdelena M. Nava, has never wanted to know details of his time in the service, Nava says, and he didn't think his family would be able to believe the occurrence anyway.

The combat veteran took part in four or five invasions on the Philippine Islands, and was wounded only once. The injury came when metal fragments from an enemy mortar struck him while he was rescuing two of his comrades; he dragged them out of danger by their harnesses.

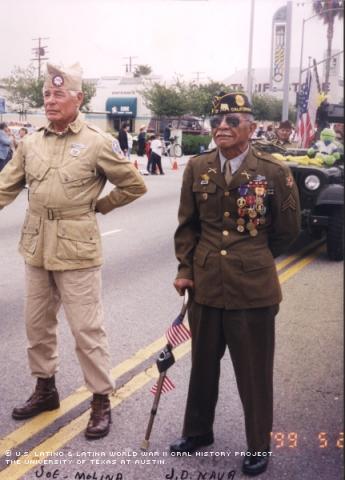

Nava and his comrades were preparing to invade Japan when the Japanese surrendered. He was soon sent home, getting honorably discharged on Jan. 11, 1946, at Fort McArthur at the rank of Sergeant. By the time his service was done, he was decorated with the Good Conduct, Purple Heart, Bronze Star, Bronze Star with Oak Leaf Cluster, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign, and World War II Victory medals. He was also awarded a Philippine Liberation Ribbon.

Despite all of Nava’s honors, he has a lot to say about the horrors of war.

"You're dead and don't know it, but you won't lie down," he said. "Because life don't mean nothin' no more."

Nava returned home and married Magdelena, or Margaret, who he knew from his childhood. They were wed in 1946 and had six children: Daniel, Frances, Barbara, Patricia, Michael and Joey.

Despite the passage of time, he says he still is affected by the period he spent in the service.

"I don't sleep nights, don't eat for three or four days and I don't know why," Nava said. "When I see a dead dog -- blood -- I see a man."

One particularly bloody ordeal in the Philippines left him hesitant to drink water or beer. "Now every time I drink water it tastes like blood," he said. "Beer started to taste like blood too, so I quit drinking beer."

The horrors of war have affected many veterans, and Nava doesn’t wish that fate on any of his children or grandchildren.

"I served time for all my family," he said. "I would never want them to go through the hardships I did."

Mr. Nava was interviewed in Los Angeles, California, on March 23, 2002, by Oscar Garza.