By Miranda Bollinger

When Ignacio Servín volunteered during World War II for a mission so dangerous his commander wouldn’t even assign it to someone, he wasn’t even frightened. He wanted to do it.

"I just kept thinking, 'If I die, it will be for a great country,'" Servín said.

But Servín and his friend, Charles "Chico" Samario, would instead go on to accomplish a feat of great courage on the island of Peleliu in the Central Pacific. Their mission involved a tunnel-like cave protecting the ammunition and supplies Japanese soldiers were using to fight and kill American soldiers and Marines. After different attempts to destroy the cave had failed, officers on the island knew some of their men would have to crawl into the hiding place to get the job done.

"The danger and difficulty of this mission is indicated by the fact that only two men volunteered, Ignacio Servín and Charles Samario. Their heroism and courage no doubt saved the lives of hundreds of our comrades," said First Lieutenant Russell Schauer, Servín's commanding officer, in a letter advocating recognition of the success.

Somehow, for nearly six decades, Servín's bravery was overlooked, however. No one honored either Servín or Samario, who died a few years ago, for what they did for their fellow Americans. Servín shared the details only with his immediate family.

In 1999, however, Servín's daughter, Belen, urged him to submit his story to The Arizona Republic, which was publishing accounts of WWII experiences. His story was selected and a friend, Larry Asman, realized Servín was a war hero. He told Servín he felt he should receive some sort of medal of recognition and that he would submit information to Arizona Sen. John McCain.

At first, the Servíns were discouraged. It was difficult to find people who were at Peleliu, in one of the war’s most bloody, costly and overlooked battles. Many of the veterans had since passed away, and more than 50 years later, Servín couldn’t remember the spellings of the commanding officers' names.

"'Well,' I comforted myself, 'I never expected a medal when I volunteered to blow up the enemy ammunition dump, and I didn't do it with the intention of getting one,'" Servín said.

Then a breakthrough occurred in 2002: Servín remembered a name -- Frank Vela. It was Vela who’d put a Browning Automatic Rifle in Servín’s hands as he was going down the hill, saying, "Here, Servín, take my BAR; you're going to need more fire power than an M-1 rifle."

Vela's name came to Servín one day, as he was leaving the house to run an errand.

"I said to my daughter, 'Belen, look for a Frank Vela in California. I think he was from California during the war, and I'm almost sure he's the one who handed me the BAR,''' Servín remembered. Within a few hours, Belen had located the correct Frank Vela.

Over Christmas in 2002, Servín and his son, Joe, visited Vela in California. The great payoff was when Vela produced a yellowed sheet of paper that contained a complete list of names and addresses of officers and enlisted men in Company A. He’d kept the list since he was discharged Feb. 9, 1946.

It took more phone calls, e-mails, queries and other research before Servín finally got in touch with Schauer, his commanding officer, who wrote the glowing recommendation for Servín.

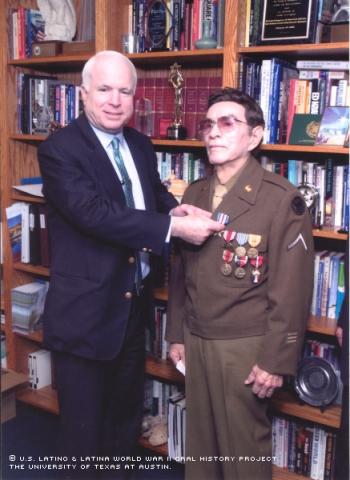

On Oct. 27, 2003, Sen. McCain's office contacted the Servíns and told them Servín would be awarded a Silver Star Medal.

Servín credits the Hispanic War Veterans of America, particularly Sam Calderon and Erwin Huelsewede, with guiding his family through the process.

Unlike the other men in his outfit, Servín had little to return to back home. His mother, Josefina Diaz Servín, died in 1928 of pneumonia, leaving young Servín, two older brothers and an older sister. Servín’s father, Donaciano, a miner in Miami, Ariz., was also in failing health.

"He knew he was going to die because he had worked in the mines for so long, so he asked this lady to take care of me, my two brothers and sister," Servín said.

Servín, who went as far as fourth grade in school, worked in the fields as a child.

"The Depression wasn't so bad because I was used to it. I was already working for $1.35 a day for nine hours irrigating cotton fields," Servín recalled. "I wasn't upset with it all; I just figured it had to be done when I was a kid."

Later, in 1943, while working in a steel mill in Pittsburgh, Calif., Servín received his draft notice. He’d wanted to go to war and all his friends had already been drafted or enlisted. So he hurried home to Phoenix to say good bye to his family before going to training.

After returning from the war, Servín had a simple, but good, life. He married Marí¬a Magdalena Menchaca three months after returning, and the couple had two sons and a daughter: Johnny, Joseph and Belen. Servín says he emphasized education to his children, and all three graduated from high school. One son earned his master's degree, and his daughter even obtained her doctorate at Arizona State University and is a professor of English at Southern Mountain Community College.

Servín has been the subject of several news stories, but he takes his Silver Star in stride. A devout Christian, he says the honor came through God.

Mr. Servín was interviewed in Phoenix, Arizona, on June 29, 2004, by Brenda Sendejo.