By Jeffrey McWhorter

Morning broke as the train rolled into Texarkana, Texas.

“Now don’t close your eyes,” the porter admonished a 22-year-old Bertha Flores, “because we’re getting close … and we’ll pass it real fast.”

For the past twenty-four hours, the eager young woman had asked the porter the same question every hour: “Where are we?” And each time she received the same patient reply, “Still in Texas.”

Two days still lay between Flores and her naval training in New York City, but she wasn’t going to miss a single town along the way. Everything was new and exciting.

When America’s young men went to fight in Europe and the Pacific, their wives, sisters and mothers joined the auxiliary military services for women. Many women, like Flores, joined the Navy as Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES). They served their country by doing everything from working on airplanes to answering telephones.

According to the Navy’s Web site, the nearly 80,000 enlisted WAVES made up 2.5% of the Navy by the end of the war. It was in this capacity that Flores served as a teletype operator, transcribing messages from around the United States and transmitting them to the officers at the Naval Air Station where she was stationed in Corpus Christi, Texas.

Flores grew up in a tight-knit Latino community in San Antonio, Texas. When she began her WAVE training in New York City, she didn’t even like smoky rooms and was overwhelmed by how fast the subway doors closed.

She was shocked when the “Anglo girls” would come back to base after a night on the town with stories of drinking and indulgence. But this never stopped her from making friends, she says.

“I learned how to tell a good person from one that wasn’t,” Flores said, “but that didn’t stop me from talking to them.”

Born Guadalupe Berta Rodriguez on March 16, 1921, she was the youngest of nine children.

“Instead of having just one mother, I had about three mothers,” said Flores, describing life as the baby of the family. “Everybody would tell me what to do.”

She adopted the name “Bertha” when she started school because her non-Latino teachers had trouble pronouncing “Guadalupe.”

She excelled in sports like softball and tennis, despite the fact that athletics weren’t geared toward women in the 1930s.

“My parents were not as enthusiastic about the kids being in school,” she said.

There was a lot of work to be done at home, so the children all had to pitch in. In fact, during the Great Depression, the family would spend a month or so in the summer working in the cotton fields, which made keeping up with school difficult, Flores recalls. She graduated from Lanier High School in 1940 – the second in her family to do so, as her sister, Carmen, had graduated three years earlier.

On Dec. 7, 1941, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and the U.S. declared war on both Germany and Japan. World War II opened a world of opportunity for this young Latino girl from South Texas.

Flores turned down the first recruiter to show up on the family’s doorstep. He was from the Army and she wanted to join the Navy, “because I liked it better,” she said.

When Flores visited the Navy recruiting station, however, she found out she was four pounds under the minimum weight of 102.

“I had to stuff myself with bananas for about a month and a half,” she said. “I made it to one hundred and one, and he said, ‘Ok, the Navy will put the other pound in you.’”

Flores’ father, Enrique Rodriguez, was a straight-laced “pick-and-shovel” laborer who didn’t believe women should work out of the home, so Flores’ decision to join the Navy at 22 didn’t sit well with him.

When she left for the three-day train from San Antonio to New York and basic training, she recalls her mother standing alone on the station platform to say goodbye.

As one of only “two and a half Mexicans” in her unit, she met people from around the country and learned that “not all of us think the same.”

When all the other girls would go out drinking, she just wanted to go dancing. “I’ve just been able to get along with people,” Flores said. “I love people from the bottom of my heart.”

She reported to the base in Corpus Christi as a seaman first class in the Navy. She reminisced about playing tennis and basketball, taking a boat trip across Corpus Christi Bay, watching planes land in the water and having young sailors smuggle her better food from the officers’ mess hall when she had to work nights.

For Flores, the war had little to do with fighting or death; instead, it was an exciting and valuable learning experience.

“What little experience I got, I thought it was worth it,” she said, “both to my country and especially to myself.”

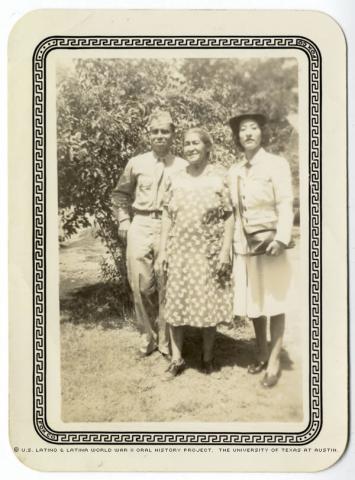

After the war, she returned to San Antonio, where she married Filbert Diaz Flores. He too had served in the Navy, as a Seabee in the Pacific. Seabees were the Navy’s renowned construction corps.

The two had actually met in San Antonio before the war, but were reacquainted right after the conflict and married in 1948. They settled down in San Antonio, where they raised their two children.

Flores focused on raising her kids, serving as a Girl Scout and Cub Scout leader, among other adventures. She still volunteers at St. Ann Catholic Church, and in 1996, spent more than a year living with and caring for her terminally ill sister. She also says she spent five years in the 1990s playing volleyball and softball in the local Senior Olympics, winning a gold medal in softball and three silver medals and one bronze in volleyball.

After her husband’s death, she cut up all of her credit cards and decided if she wanted to buy something, she’d have to save for it.

When her granddaughter was considering joining the Coast Guard, she asked Flores’ advice: “If I was young enough, I would do it again,” said Flores in an unassuming voice. “Little bit of here, little bit of there, I put it all together. I think I have done a lot.”

Mrs. Flores was interviewed in San Antonio, Texas, on August 4, 2007, by Raquel C. Garza.