By Meridith Kohut

There were ways to battle tedium in the long stretches at sea: poker games, movie nights and dishes of ice cream. But for Gilbert Garcia of Houston, Texas, it was mostly the poker winnings he relished.

At sea, Garcia was perhaps the best poker player on ship. He boasts being able to win hands despite other players sharing their cards with one another in an effort to beat him.

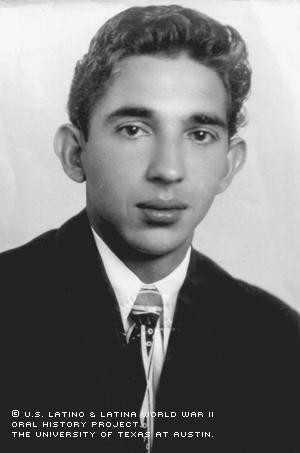

Garcia was born March 11, 1924, in Mercedes, Texas, in the Rio Grande Valley. His mother, Manuela Garcia, later moved with Garcia to the Mexican barrio of Magnolia in Houston, Texas. Manuela raised him as a Catholic and saw to it he attended De Zavala Elementary School. He dropped out after the eighth grade at Dow Junior High School, and worked painting cars to supplement his mother's income.

Garcia wouldn’t know who his father was until he was 65 years old. He was surprised when he found his father was William Brooks, the father of one of his closest childhood friends, and the owner of the ranch in South Texas, where he lived as a child.

Garcia originally had plans to enlist in the service with his friend, Homer Hernandez, however he overslept the morning they were to meet at the recruiting office, and Hernandez joined the Army without him. Hernandez was sent to the Philippines, where he was killed on the second day after Pearl Harbor.

Garcia was later drafted when he was 19 years old. When he reported at the recruiting office, he says he said he’d prefer going into the Navy, but was refused because the officer said the Navy had already met its quota. A Navy recruiter in the office eavesdropped on their conversation and pulled him aside. "See that Navy car over there?" he asked. "Run over there and jump in!" Garcia did, and the resourceful recruiter enlisted him.

Garcia completed boot camp in San Diego, Calif. After testing for specialty training, he was assigned to torpedo school, which he says was the hardest. He pledged to himself to "do the best I could do with it" he said, and struggled through the school for three months. He was at a huge disadvantage because the other students in his class all had a few years of college, and he’d not even gone to high school. Completing torpedo school would have given him Seaman 3rd Class rank, which is equivalent to being a sergeant. However he decided to pass on the opportunity and applied to go to sea.

Garcia was assigned to the crew of a carrier ship, the USS Hammondsport, which transported trains, planes and troops from the Fleet and Industrial Supply Center in Oakland, Calif., to all of the islands in the Pacific.

He traveled aboard the Hammondsport to Hawaii, Fiji, the Gilbert Islands and several more he couldn’t remember. The ship would return to Oakland or San Diego about once a month to get more cargo. Oakland was his favorite port, because he could get to San Francisco from there. In San Francisco, he and his friends hung out at a café, whose owner had five beautiful daughters and treated the sailors like "rich kinfolk,” letting them eat for free.

Garcia says he and his fellow shipmates loved going out drinking and meeting the local women of where the Hammondsport had docked. The crew always heard about how friendly the girls in Australia were, he says; however, unfortunately for the crew, Australia was the only place their ship wouldn’t sail to.

Garcia's carrier was never under attack, yet he says he always feared it could be, due to it carrying important cargo. While on duty, his jobs ranged from painting and scrubbing the decks to loading 20-mm guns. He was able to load the guns because he was good at it, despite not being very strong, and because the rest of the crew was afraid of getting their hands caught in the process. He occasionally was allowed to fire them as well, but the only target he ever shot at was a plane out of range, about five miles away. They didn’t see much action, he says.

He recalls the most gunfire he witnessed was in San Francisco, when the news broke Japan surrendered. Garcia's ship had just docked in Oakland. As he walked out, a man approached him and told him about the surrender. Everyone was celebrating by shooting their guns and going crazy in the streets. He says it was the closest thing he saw to a war zone during his service.

Japanese officials signed articles of surrender aboard the battleship Missouri, anchored in Tokyo Bay on Sept. 2, 1945. The greatest war in the history of mankind had come to an end, and the United States had emerged from it victorious and in a position of unprecedented power, influence and prestige. Garcia was discharged soon after, on January 3, 1946, and returned to Houston.

Back in Houston, Garcia reunited with an old friend, Minerva Herrera, upon whom he’d been sweet; the two married in 1947. Garcia went to photography and barber schools on the GI Bill, but decided they were both "busts," that didn't pay well. After a short stint selling the Houston Chronicle, he returned to painting cars. He opened his own shop, but didn’t like all of the paperwork and overhead costs so he went back to work for a big car dealership. Minerva worked as a secretary for her brother, Johnny Herrera, a well-known and prominent attorney who fought for Latino rights and tried police-brutality cases.

The Garcias have been married for 56 years and have two sons: Gilbert Jr. and Robert.

Garcia has been retired for 14 years and has settled down considerably since his rambunctious days in the Navy. The couple continues to reside happily in Houston.

"It's been a good ride," Garcia said. Lucky at cards and considered lucky in life, this poker player feels he was dealt some pretty good hands.

Mr. Garcia was interviewed in Houston, Texas, on May 6, 2003, by Ernest Eguia.