By Maureen King

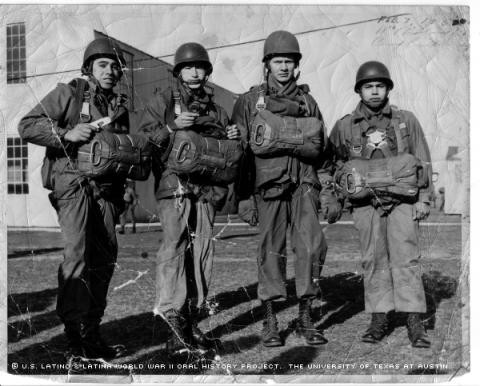

It had always been a fascination to him, something he’d seen in the movies.

He knew he could do it and do it better than anyone else, he says, because he was a Mexican. The fascination: jumping out of an airplane.

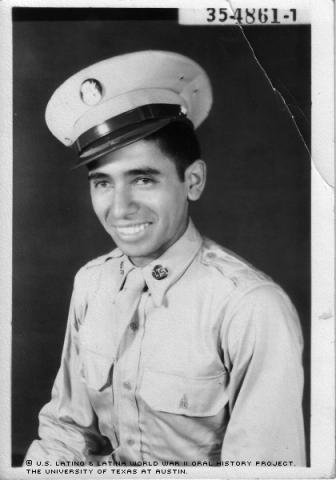

The challenge led George M. Castañeda to serve as an Army paratrooper in the 11th Airborne Division during the Korean War.

"I'd do it again if they asked me to," Castañeda said. "If I had to go, I'd go on to the airborne. It's in my blood. That's when you know what you're made of. Either you got it or you don't got it."

Influenced by his older brother, who served in the 7th Division during the Korean War, Castañeda knew he wanted to fight for his country, too. He was tired of the life of a migrant worker.

"I didn't want to be in the fields working the farmer jobs," he said. "I didn't like them. I still don't like them."

Born in 1927 in Dallas, Texas, Castañeda remembers always moving from one school to another while growing up, and the annual family trips to Michigan to work in the fields. His parents, two brothers and a sister would all work together doing different field jobs, such as picking vegetables and fruits.

In his first job in the early 1940s, Castañeda says he earned 35 cents an hour. Although working in the fields meant laboring in the sun and receiving poor pay, he couldn't land a job in the factories because he was too young.

Working in a factory was seen as a better opportunity because it paid good money and you made a decent living, he says.

"There's always been Mexicanos in Michigan, especially the migrant workers who come every year," Castañeda said. "As soon as they get a good job, they leave farm work and start in a factory like General Motors, Ford and Chrysler."

But before Castañeda would have the chance to begin his career in a factory, he joined the U.S. Army Airborne -- a decision that would leave him forever changed.

He joined the Army in 1948 and served as a sergeant in the airborne in 1950 and 1951. Those who were unable to pronounce his last name knew him as "Sgt. Castanita," he said.

Castañeda began his basic training in Fort Knox, Ky., and then went to airborne school in Japan. When the Korean War began, he was sent with the 187th Infantry Regiment to China to rescue prisoners who’d been captured in a surprise invasion.

"They sent us out there as quickly as possible to save them," Castañeda said. "So that's what we did."

That was his first combat jump. On his second jump, however, he wasn't as lucky. He sustained a bullet wound to the leg and was sent to Tokyo General Hospital. When he recovered, Castañeda recalled, "My commander said, 'I'm glad to see you back because we're ready to make another jump.' And I said, 'I should've stayed in the hospital.'"

Castañeda remembers that particular combat jump. He was sent in to pick up all the dead and wounded and to plug up the battle line on the 38th Parallel. The Chinese had overwhelmed the U.S. soldiers in numbers, forcing the Americans to put all of their machine guns and artillery right on the line. When they ran out of ammunition, the U.S. soldiers had to fight in hand-to-hand combat

"What saved me was my mother prayed for me all my life," said Castañeda in tears. "I guess I was one of the lucky ones that got out of there. I was one of those that survived all that stuff."

Although Castañeda’s memories of the war continue to live with him, there are some things, he says, that he would rather not remember -- such as becoming a killer.

"I remember the first three [enemy soldiers] I shot," he said. "The first ones I killed, I became a killer because that was the way it was. War is war, either you kill or be killed."

The three Chinese soldiers Castañeda killed had been running at him, two with rifles and one with a radio and maps.

"They were trying to find out where the battle line was," he said. "They were trying to find out so they could radio back for artillery and mortar fire and tanks and everything they had so they could start killing us."

As soon as he saw the soldiers coming straight at him, Castañeda opened fire with his machine gun, killing two and initially wounding the other. He was able to get hold of the enemy's radio and maps of the terrain.

"My lieutenant told me, 'Good work, Castanita' for killing them people," Castañeda recalled. "I didn't say anything, but I didn't feel good because I had to kill them. Otherwise, they would have killed me. So what's the difference."

To forget about these painful wartime experiences and to pass the time, Castañeda says he found solace in drinking and singing with his war buddies.

"We had a break in the big battles," he said. "There was nothing to do but get in the foxholes and wait for the enemy. You remember all your lifetime, what you did when you were going to school, and you remember a lot of things."

Now, Castañeda doesn't look back on his life with sadness. Instead, he can reflect with a feeling of accomplishment.

He earned a U.N. medal, the Purple Heart, a Good Conduct Medal, five stars -- one for each jump he completed behind enemy lines -- and the title of Senior Jumper for completing more than 30 jumps.

Castañeda had braved the challenge of becoming an Army paratrooper. He never had to return to the field jobs as a migrant worker after the service. Instead, he went on to work for General Motors for 49 years in Michigan, where he later married.

"I can't deny that a soldier's a soldier," he said. "You might call me a soldier of fortune because I survived all that stuff, all the things I had to do in the Airborne Army."

In March of 2003, Castañeda was awarded the Medal of Freedom from the Korean community at McCombs College in Warren, Mich.

Mr. Castañeda was interviewed in Saginaw, Michigan, on October 19, 2002, by Maggie Rivas Rodriguez.