By Valerie Jayne

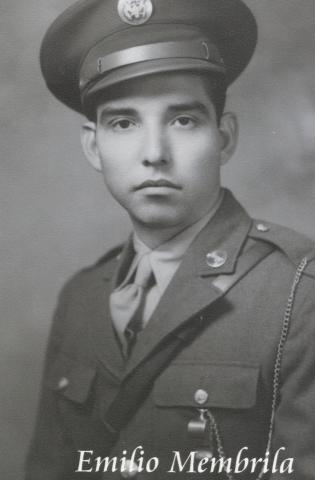

As a young boy growing up in Clifton, Ariz., Emilio Muñoz Membrila played war games with his friends, inventing different maneuvers and strategies. Later, during World War II, he’d be engaged in historic battles in the European Theater, fighting in the frigid German forests during the Battle of the Bulge and getting taken prisoner for six months.

"It was the worst barrage U.S. troops ever encountered," said Muñoz Membrila of the Battle of the Bulge, Hitler's last major offensive. "It was supposed to have been a quiet sector."

Muñoz Membrila, who’d dropped out of high school after two years, was drafted in August of 1942. At the time, he was working at an electrical warehouse owned by Bechtel Construction, where he issued supplies to electricians constructing a smelter and a mill.

The U.S. Army initially posted him as a gate guard at Camp Beale in California, but he later began infantry training as a 60-mm mortar gunner at Camp Atterbury in Indiana, where he was placed with Co. A of the 424th Infantry Regiment of the 106th Infantry Division.

While on leave from training, in January of 1944, Muñoz Membrila married Vincenta Mena. Then, on Oct. 21, 1944, Muñoz Membrila was transported to England for advanced infantry training. Afterward, he entered battle in France and Central Europe, arriving in France on Dec. 5, 1944.

That month, at the Battle of the Bulge in Ardennes, Muñoz Membrila was captured by German Panzer Division soldiers. He’d be a prisoner of war for the next six months.

Meanwhile, his wife, Vincenta Mena Membrila, joined a Women's Army Corps Medical Section. She was assigned to the 20th Regiment’s Company 2 at Fort Oglethorpe in Georgia and then to the Presidio in San Francisco. She served for 14 months.

Allied leaders didn’t expect the Germans to strike a major counteroffensive, especially in the Ardennes; therefore, the Allies failed to take greater precautions to protect the Belgium area.

Muñoz Membrila says two regiments in his division were "wiped out," leaving only his regiment, the 424th, to fight the Germans.

His sergeant gave orders to defend a crossroad near Winterspelt and shoot at anything in sight, but the darkness, rain and fog hindered their vision.

Only one day into the battle, on Dec. 17, 1944, the U.S. Army reported Muñoz Membrila missing in action. A telegram home to Vincenta in Clifton, dated Jan. 19, 1945, from the Active Adjutant General Dunlop, expressed "deep regret that your husband, Private First Class Emilio M. Membrila has been reported missing."

Muñoz Membrila, one of 1,277 Americans captured in the Battle of the Bulge, was transported by train to Stalag XII A in Limburg, Germany. He remembers being crammed into a boxcar along with sick and dying soldiers. The train traveled slowly and stopped frequently, making the trip almost unbearable, he said.

When he arrived at Limburg, the Germans divided the American prisoners into two groups -- one of officers and another of enlisted men -- and sent them to different barracks. Muñoz Membrila accidentally got herded to an officer barrack and was ordered to leave and join enlisted men in the other barrack.

As he walked by himself through a gate and down an alleyway, he worried the guards along the towers might think he was trying to escape. However, he arrived at the other barrack safely. Later, a British bomb raid hit the officer barracks, killing all of the captured American officers, including his captain, he recalls.

The Germans then forced Muñoz Membrila and other American prisoners to walk without food and water for three days to Oflag III A in Lukenwalde, a camp near the outskirts of Berlin.

He and his fellow prisoners watched American bombers fly over Berlin.

"Our friends are so close to us and yet they can't think of anything to help us out," Muñoz Membrila remembers saying.

He tried to keep his spirits high during his time as a prisoner, writing to his mother, Elena Muñoz Varela, back in Clifton that he wished his family the best of health and he hoped for a safe return home.

"I have dreamed of you all constantly and of all those at home but perhaps one of this days soon with, God's permission, this dreams will become real," wrote Muñoz Membrila in one letter, which he signed "Milio."

His imprisonment at the camp in Lukenwalde was shortened when the Germans sent him to a labor camp in another small town, where he worked on a railroad.

Muñoz Membrila says he thought working in a labor camp would be better than staying in a concentration camp with thousands of people.

His dream of returning home eventually came true when the U.S. 7th Armored Division liberated the town from German control.

A joyous Muñoz Membrila celebrated his liberation with other rescued captives -- including Russian, Czechoslovakian and some other ethnic women -- by drinking beer and singing at a tavern located in the center of town. Then he flew to Le Harve, France, and soon after, to New York City.

"It was a happy moment to see the Statue of Liberty with the torch -- young, good old U.S.A.," said Membrila of his return in June of 1945.

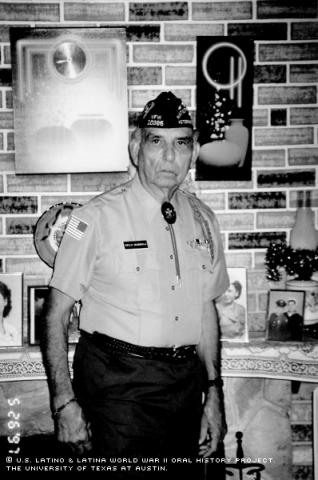

For his service in the European Theater, Corporal Muñoz Membrila earned a Bronze Star Medal, American Defense Medal, EAME Campaign Medal with three Battle Stars, POW Medal, Battle of the Bulge Medal, Good Conduct Medal and a Combat Infantryman's Badge.

He was also reunited with Vincenta, who took a two-week leave from the WAC, and was then sent home for a 30-day leave. Later, he was sent to Camp Beale, Calif. On weekends, he traveled to San Francisco to see Vincenta.

Throughout his service, Membrila says his native language and culture remained strong in his mind, even though his company consisted of mostly Anglos.

He eventually returned to Clifton, where his mother and grandmother had raised him and his seven siblings. The local newspaper carried a story about his return home in December of 1945. He says he felt grateful he hadn’t been wounded in the field and he’d been ordered back to the right barrack on that fateful day.

"The good Lord was with me," Muñoz Membrila said.

But returning home, and back to a "normal" life, seemed challenging to him. A doctor advised him to work hard and keep busy. Muñoz Membrila worked as a refractory builder -- constructing and maintaining furnaces for the smelting of copper ore -- for Phelps Dodge Corporation until his retirement in 1983.

"As long as I'm happy, that's all that matters to me," Muñoz Membrila said.

Vincenta died of a stroke in 1993. At the time of his interview, Muñoz Membrila lived in the small community of Thatcher, Ariz., with his only son, Michael, who was born in June of 1946.

Mr. Muñoz Membrila was interviewed in Tucson, Arizona, on January 5, 2003, by Violeta Domniguez.