By Evelyn Ngugi

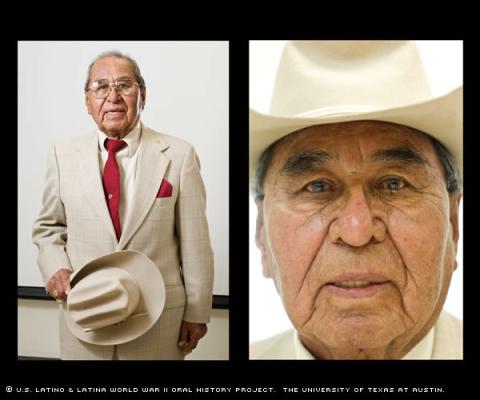

Four days after his eighteenth birthday, rookie soldier Derlin Loya set sail for Germany on May 18, 1946.

By that time, Germany and Japan had already surrendered to Allied Forces, so Loya never had to face day-to-day combat during his nearly three years as a truck driver in Europe. That’s not to say, however, that he and the rest of the First Infantry Division’s Headquarters Battery weren’t in a dangerous situation. For example, gun shots suddenly sounded one day when Loya was driving a jeep for a first lieutenant.

“All of a sudden, ‘boom,’ before I could pull out my .30-caliber,” Loya recalled. “Them people were mad because they lost a war. Thank God we survived.”

Loya was stationed in Munich and Nuremburg, as well as served guard duty in Dachau, the location of the first Nazi concentration camp in Germany. The treatment he received in the Army was much different from that which he received back home in South Texas, he said.

“Ninety nine percent better than here,” Loya said.

It is impossible to know exactly how many Latinos fought for the United States in World War II because the military did not officially recognize Hispanics as a distinct ethnic group.

“When I joined the Army, there were only two races – black and white. We were classified as white,” Loya said.

It wasn’t so, however, back in Beeville, Texas, about 50 miles northwest of Corpus Christi, where Loya was born and raised. He recalled the local public schools being segregated into black, white and “Mexicano.” And if he wanted to eat in certain restaurants, he said he had to dine in the kitchen.

Loya wasn’t fluent in English until high school, which made formal education rough.

“How can you tell the teacher, ‘May I go to the restroom,’ like I can now?” Loya said. “All I did was get up and go to the restroom and come back. She’d get mad and send us to the principal.”

Life wasn’t easy at home, either. Loya’s mother, Gregoria Rodriguez Loya, washed and ironed clothes for Anglos, and Loya’s cowboy father, Guadalupe Loya, died of tuberculosis and other complications in 1944. Loya had two sisters and five brothers, three of whom served in the military.

During his ninth-grade year, on Dec. 7, 1945, Loya left high school for good when he enlisted in the Army, after realizing his mother needed financial help. One glaring clue was that the family couldn’t afford shoes, thus forcing the Loyas to attend school barefoot.

“When my dad died, nobody was bringing money in the house,” Loya said. “Of course, everything was cheap in those days, but that’s what made me quit school and join the Army.”

Before he left Beeville, his mother told him, “God bless you,” wrote Loya after his interview.

He was honorably discharged from the Army’s 1st Infantry Division on Nov. 19, 1948, at the rank of Corporal Fourth Grade. For his service, he earned the WWII Victory Medal and Army Occupation Medal.

Loya then raced home to see if his mom was still alive.

“I had it in my mind that my mother had passed away and they didn’t want to tell me,” said Loya, who turned out to be wrong.

Gregoria Loya died in 1979 of emphysema at the age of 81.

“She lasted a long time,” Loya said.

At 26, Loya married Ofilia Olvera, who worked in the local jewelry store in downtown Beeville. They had 3 kids – Mike, Joe and Patricia.

After holding several different jobs, Loya started in 1968 as a bus boy at Chase Field Naval Base in Beeville, and was promoted to Cook sometime later. He put together meals for as many as 2,500 people, at a starting salary of $2.22 an hour.

The base closed in 1993, at which point Loya retired at age 65, earning $15 per hour.

Compared to his own childhood, Loya said Latinos have more opportunities in the States. For example, his daughter, Patricia, attended college and now works for IBM.

“Nowadays going to school, by the time [a child] reaches first grade, he talks better English than I can and explain himself to the teacher,” Loya said. “These kids have come a long way.”

Newer generations of young adults also have had it better than he did at their age, said Loya, whose words of wisdom were:

“Stay on the right track. Education is number one.”

Mr. Loya was interviewed in Beeville, Texas, on January 10, 2009, by Adolfo Dominguez.