By Emma Graves Fitzsimmons

When David Loredo was shot in the stomach in the hills of the Philippines during World War II, his first thought was he’d never see his mother again.

"I remember standing there in a daze," Loredo said. "I felt like I had gotten hit with a huge rock. I was scared I was going to die."

It was March 17, 1945, and Loredo had been leading his squad on a reconnaissance mission in the hills when he and one of his scouts were shot. He was told he "cussed out" his captain, blaming him for the injury, but doesn't remember it because he’d been given morphine.

"I felt we were let down," Loredo said. "We had advised [our superiors] to put the artillery up before we hit, and they didn't."

Almost 60 years later, Loredo is convinced his faith helped pull him through the near-fatal wound. He was taken on a stretcher to the nearest substation and reached a hospital that evening.

Loredo, who was raised in the Pentecostal Church, was encouraged by his mother, Catarina Perez Loredo, to attend services every Sunday. He says that when the war began, churches were open 24 hours a day, allowing his mother and family to pray for him regularly.

"I feel that God played a big part in my coming back," Loredo said. "The prayers of my mother and sisters helped a lot."

While he was in the hospital, Loredo received the Purple Heart. Later, he’d also earn a Silver Star Medal for heroism, Bronze Arrowhead, Good Conduct Medal, Asian-Pacific Campaign Medal with one Bronze Campaign Star, WW2 Victory Medal and Combat Infantryman's Badge.

By the time Loredo had recovered from his wound, the war was almost over. His company had been told it would have to start training again to prepare for the invasion of Japan. Predictions forecasted 75 percent of their men would die in the fighting.

The invasion became unnecessary when the Japanese surrendered after the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August of 1945.

Loredo was born March 20, 1925, in Sinton, Texas, 30 miles north of Corpus Christi. Both of his parents were born in Mexico. His father, Cirilo Loredo, didn't have a steady job but served as a laborer wherever he could find work.

The family moved to Victoria and then Alvin, where Loredo completed the fifth grade at age 13. In those days, he says Latinos and whites attended the same schools, but blacks were segregated in their own schools. He also notes that beyond the schools, all three ethnic groups lived in their own separate neighborhoods.

The oldest of three brothers, Loredo began working at age 15 as a helper for a tile setter and cement finisher for $9 a week. His father was a laborer.

The family worked picking cotton a few months a year to earn extra money. They got 25 cents for every 100 pounds of cotton picked, Loredo said.

"My dad's idea was that everyone could contribute and make a little more for those months and buy some shoes and maybe some clothes for the winter," he said. "He liked that kind of work."

Loredo was drafted in 1943 when he was 18. He was sent to Camp Walters in Texas for 17 weeks of basic training.

He saw his family once before being shipped to the South Pacific, where he joined the Army's Company L, 169th Infantry Regiment, 43d Infantry Division. He recalls few other Mexican Americans being in his unit.

Loredo saw his first combat action in the invasion of the Philippines on Jan. 9, 1945. His unit encountered little resistance because Japanese forces had retreated inland, Loredo says.

"We regrouped and headed for the hills," he said. "The enemy, they were in the caves and trenches. They could move all over the place without being seen because they were dug in."

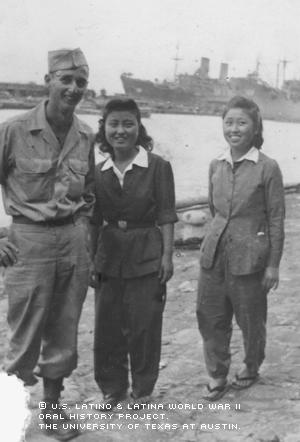

After the Japanese surrendered, Loredo and his company were sent to Yokohama, Japan, in September of 1945 to help in the occupation of the country. They went from house to house to disarm the Japanese people.

Loredo recalls that in the Philippines, the people had been happy to see the American soldiers, waving peace signs and trying to hug them. The reaction in Japan was very different, however.

"The soldiers were not friendly to us," Loredo said. "They didn't like us, and we didn't like them either. The women, children and old people were nice to us."

After disarmament was complete, the soldiers had little to do. Loredo took a train to Tokyo to explore the captured capital. American soldiers could ride the train for free.

"There was not much to see," Loredo said. "Everything was bombed and burned."

While he was stationed in Japan, he saw firsthand the devastation that had been brought by the war.

"There was a lot of hunger," Loredo said. "In the trashcans where we dumped out leftovers, they would fight over that. I can't help but feel sorry for all those people that were hungry."

He returned to the U.S. a few months later, and was discharged at Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas, on Dec. 18, 1945. When he came home, he spent a lot of time "partying" with friends who’d also been fighting in the war. Eventually, he attended a watch repair school with funding provided by the GI Bill.

"I wanted a job where I'd be clean," Loredo said. "I didn't have the schooling to go into refrigerator repair."

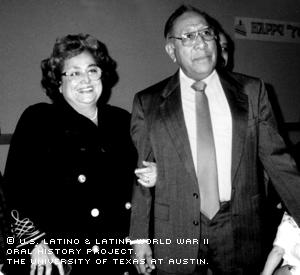

At 78, he’s still a watch repairman. He lives in Houston with his second wife, Marta, a seamstress.

Loredo has four sons and four daughters, nine grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.

Mr. Loredo was interviewed in Houston, Texas, on May 23, 2003, by Ernest Eguia and Paul R. Zepeda.