By Stephanie De Luna

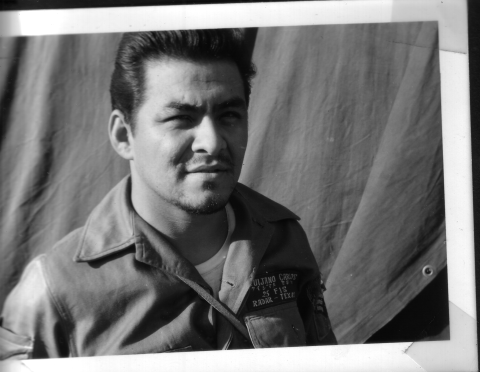

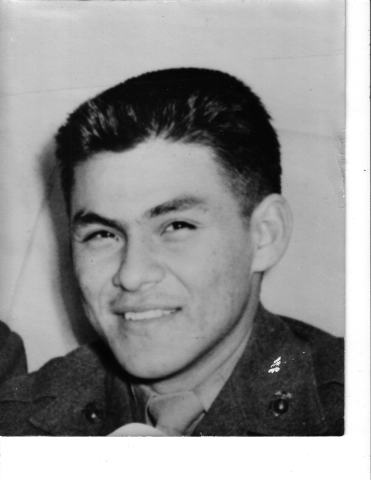

Carlos R. Quijano, a native of San Antonio’s west side, never imagined that his future would include world travel and achievements most people couldn’t accomplish in two lifetimes. Over 23 years, he served in both the Marines and Air Force and participated in military operations in Korea and Vietnam.

Quijano was born Nov. 4, 1932, and grew up in Alazán Apache Courts, a housing project in San Antonio, Texas. He attended Pauline Nelson Elementary School and Washington Irving Junior High, graduating from San Antonio Vocational and Technical High School in August 1951.

His mother, Rosa Ambriz Quijano, was a native of Monterrey, Mexico, and his father, Robert M. Quijano, was from Matehuala, Mexico. His father, who had a third-grade education, worked as a printer for Naylor Printing Co. and earned about 100 dollars a week. Quijano says the weekly paycheck was enough to support the entire family.

Quijano’s mother graduated from high school and chose to stay home to raise the family. “She was really good at sewing,” Quijano said. “She made all of my sisters’ dresses. She made all of my shirts.”

Quijano grew up with six siblings: Rose, Robert, Carmen, Eddie, Theresa and Frank. “We were very united," Quijano said. "My dad didn’t want us to forget each other. He wanted us to be there for each other and help each other.”

Quijano recalls his parents as strict but loving. They restricted their children from speaking Spanish at home. “They wanted me to get a good understanding of the English language, and they thought it would hinder me if I spoke Spanish,” he said. “They didn’t want me to have an accent.”

However, Quijano said, not knowing Spanish led him to struggle in school because 80 percent of the students were Hispanic, and Spanish was spoken throughout the school. “I was having a hard time with my English," he said. "I had no problems speaking English, just writing it.”

Once when Quijano visited his maternal grandmother and told her he was hungry, she looked at his aunt and said, “Tell that gringo if he wants to eat here, he better speak Spanish.” From that day on, Quijano learned Spanish.

Quijano remembers his grandmother as “a very devoted and very humble lady.” She went to church every day and was mostly the reason why his family celebrated religious holidays. Quijano says he had a close relationship with his grandmother.

“I took her everywhere,” he said. “I used to take her to watch Mexican movies, and that’s also where I learned my Spanish. I had to remember what the actors were saying so I could learn the language.”

Quijano said his grandmother played a great part in his life until the day she died. In 1952, Quijano was aboard a ship to Korea when he was notified that his grandmother was on her deathbed in Houston, Texas. He was allowed to return to Texas.

“I saw her, held her hand and kissed her forehead," he said. "I told her I’d be back because I was going downstairs to go get a cup of coffee.”

When he returned, she had died. A doctor asked Quijano if he had seen her. He told him yes, and the doctor replied, “That’s what she was waiting for.”

Quijano enlisted in the Marines the day after he graduated from high school. He spent six weeks in a boot camp in San Diego, California. He then went to Quantico, Virginia, for ordnance school. After 12 weeks of training, he was sent to Camp Lejeune in North Carolina.

“Once I left home, I started seeing discrimination,” Quijano said. On the way to Camp Lejeune, Quijano stopped to eat in Schulenburg, 102 miles east of San Antonio. An old man arrived with his grandson and granddaughter. Quijano opened the door for them, but the woman at the counter said the family couldn’t enter. Quijano asked why, and she told him they weren’t allowed to eat inside because they were Mexican.

"I’m Mexican,’” he told her.

The woman told Quijano that they couldn’t discriminate against him because he was in a military uniform. “So I got my sandwich and Coke and went to go sit outside,” Quijano said. “If they couldn’t eat in there, I couldn’t eat in here.”

Quijano was sent to Inchon, Korea, in 1952. He remembered that when he arrived, his ship was covered in ice. He and the other Marines received gloves, wool caps and coats. They also got “Mickey Mouse” boots -- heavy, insulated footwear -- to keep their feet warm. Quijano commanded about a dozen men in a machine-gunner unit.

“At night [the North Koreans] used to shoot rockets at us, and we would shoot back at them,” Quijano said. “Every morning there was a sniper up on a hill. We would come up to wash our faces, and he would be waiting for us.”

In February 1952, Quijano found out how dangerous his job was. A lieutenant asked him to go out to a bunker, and as he approached the bunker a mortar struck the entrance.

“A piece caught me in my head,” Quijano said. “I thought I was sweating, but the lieutenant told me I was bleeding.” He was put on a stretcher and carried to the hospital. “I could hear them sewing me up,” he said. “I was sent back on the line three days later.” Quijano later received a Purple Heart.

After a year in Korea, Quijano returned to the United States and was promoted to sergeant. He was offered a chance to travel to Hawaii but wanted to go home to San Antonio because he missed his family.

“It was a big mistake. There were no jobs here,” he said. “My dad told me, ‘You need to do something with your life.’”

That’s when Quijano decided to travel to Chicago and California. He was about to join the military again with a friend while in California, but his friend was in the Air Force and already had an assignment. So Quijano traveled to San Antonio to join the Air Force.

Quijano was assigned to Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, for one year. He was next stationed at Naha Air Base in Okinawa, Japan, and then Seymour Johnson Air Force Base in South Carolina. He went back to Myrtle Beach and then to MacDill Air Force Base in Florida.

Before he went to MacDill, his father told him it was time to get married. Quijano had been dating Mary Louise Hernandez for about 10 years on and off and one day called her and asked her to marry him. She said yes, and they married Sept. 1, 1962, when they were both 29.

Quijano and his wife had five children, three boys and two girls. “My wife practically raised the kids because I was always gone. I’m so glad that she was able to do that,” he said.

While in the Air Force, Quijano and his family lived in England and Spain and traveled across Europe.

Quijano made sure his children valued education. “When my kids were growing up, that’s one thing we mentioned,” he said. “They needed to go to college.”

Quijano volunteered to serve in the Vietnam War. In Vietnam, his main job was to repair aircraft and guard the air fields. He stayed for a year.

“They bombed us. They threw rockets at us. We were under the constant threat of them coming in and booby-trapping our planes. We had to protect what we had,” Quijano said. “It was different being in the Air Force. We didn’t have to find the enemy, but we still had to protect what we had.”

Quijano’s final discharge from the military was in February 1974. He was a staff sergeant.

He and his family settled in San Antonio. He attended San Antonio College and studied electronics. He worked at Santa Rosa Hospital for 21 years, where he worked on equipment that had been used during surgery. After that, he worked at Southwest General Hospital, Seton Hospital in Austin, McKenna Memorial Hospital in New Braunfels and finally, University Hospital in San Antonio. He retired at 71.

Quijano remained involved with military organizations and was a member of the Purple Heart Association, Alamo Marine Corps League and other organizations. At the time of his interview, he was volunteering twice a week at University Hospital and once a week at Tejeda Hospital.

Looking back on his military career, Quijano said, “It was war, but it’s a job we had to do.”

Quijano tries not to let his battlefield experiences get in the way of his everyday life.

“I watch war movies, but I don’t dwell on them,” he said. “The more you worry about it, the crazier you are going to get.”

Quijano says the government has done a good job of providing treatment for veterans, but it’s up to individuals to take care of themselves.

“You need to have a strong mind to not let this overpower you,” he said. “The government’s trying, but if you don’t want to work with them, they can’t cure you.”

Quijano says he has enjoyed his life, but it has not been perfect. “I’ve had mishaps, but I always seem to come out of it in a positive way,” he said.

Mr. Quijano was interviewed by Stephanie De Luna in San Antonio on April 26, 2011.*

Voces Oral History Project attempts to secure review of all written stories from interview subjects or family members. However, we were unable to secure that review for this story. We will gladly accept corrections from the interview subject or designated family members. Please contact voces@utexas.edu.