By Robert Reiss, California State University, Fullerton

"You could hear the tanks coming. You could hear the squeak, the tracks squeaking and the motors running. You could hear them coming. The Americans and the infantry were aware that they were no match for that kind of assault. So we picked up our machine guns and retreated. ... When we asked the sergeant where [his men] were, he replied, 'They are gone. They sprayed them in their dugouts. They killed them all.' "

That was how Bennie Trujillo described one intense point in the month-long Battle of the Bulge, the last major German offensive of World War II.

For Trujillo, helping wounded soldiers on the front lines in Europe was a world away from Watrous, N.M., where he was born and raised. The combat He had joined the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) at the age of 16, not long after his father, Ventura Trujillo, died in a work accident. The CCC was a federal program set up for unemployed and unmarried men during the Great Depression. It was a way for Trujillo to help his mother support the family. When he was sent to a Conservation Corps induction camp at La Cueva, N.M., Trujillo got his first taste of what military life might be like.

"They induct you, as if you're going into the Army. You had to get the shots, and they had to issue you clothing" to wear every day, Trujillo said.

After the CCC, Trujillo returned to Watrous and started sheet metal, welding and machinist vocational training at Highland University in Las Vegas, N.M. The training lasted about six months, after which he made his way to San Francisco, where he worked in a shipyard. At lunchtime, he remembers watching rallies to sell war bonds.

Trujillo chose to enlist, even though he was only 17 years old. He lied about his age and joined the U.S. Army on July 12, 1943. Like most Latinos, he said, he wanted to join the infantry.

"It didn't quite hit me, except for the fact that we were at war at that time," he said. "And there were no negatives about going into the military. No negatives at all. Everyone wanted to go."

He was first sent to Camp Barkeley, near Abilene, Texas, for basic training. He said that he had no problem adjusting to military life because of his experience with the CCC.

After three months, he was sent to Louisiana. There, Trujillo became part of the 99th Infantry Division, 393rd Regiment, 1st Battalion Medical Detachment. After finishing maneuvers in the Louisiana swamps, the 99th Infantry Division was sent to Camp Maxey, near Paris, Texas, where he undertook additional medical field training.

Trujillo was attached to his field unit, Company D, as a litter bearer with aspirations of becoming an Army medical corpsman attached to a Company. One of his first hands-on experiences was at the base hospital, where he assisted the autopsy of a soldier who was killed in training.

Trujillo eventually was sent to Providence, R.I., where he boarded SS Argentina headed for Southampton, England, in 1944. While on the ship, Trujillo had to care for soldiers who had gotten sick onboard.

After about seven days at sea, SS Argentina landed in Southampton. Trujillo recalled that a week or so later, the men embarked on a Dock Landing Ship across the English Channel to Le Havre, France.

Members of his unit were out in the open all the time, and occasionally he saw artillery fire and small arms fire during his early time in France and Belgium, although they did not take part in any major battles in the first months, he said.

He said that his first combat experience was at the Battle of the Bulge, on the Siegfried Line between Belgium and Germany. Trujillo recalled seeing pillbox bunkers and dragon teeth anti-tank traps a couple hundred yards away. "The night before the Battle of the Bulge started, we heard artillery coming in a lot," Trujillo said. "Like a lot of artillery, boom, boom, boom, boom. Then we would hear the shells coming over like 'Screaming Mimi's' [short-range rockets developed by Germany]. But when they got to where we were, they would hit the pine trees and just go pop. That was all they would do, but they kept coming for about two to three hours."

On the second night, he said, the the payloads bursting above ground were much more effective.

"It must have been around 9 p.m. the next evening, and they started again," he said. "Only this time, when the shells started hitting the pine trees, they started exploding. And that went on and on and on -- all night long." Shrapnel from the blasts hit many of the men in his unit, but he was able to take care of them and send them back to the aid station.

At dawn, he said that he had awakened to the sounds of a lot of small arms fire and "burp guns" [German submachine guns] going off some distance to the right of them, where Company C was stationed. In Company D, where Trujillo was located, the men could see heavy German Tiger tanks coming through the forest, firing their guns.

That is when they were ordered to retreat, he added.

The next thing he remembered was seeing one of the sergeants from Company C walking out of the forest with two or three of his men. Trujillo said that his lieutenant asked the sergeant where his unit was.

"They are gone. They sprayed them in their dugouts. They killed them all," the sergeant replied, according to Trujillo.

The GIs in his area soon realized that they were in German-held territory.

"We were now behind enemy lines, and it took two days for the company to get back to the American line."

"When we started finally making contact with the American forces coming back, it was at night," he said. "I remember getting closer to our unit, and the Americans thought that we were Germans coming through the valley. And they started with the artillery." As Trujillo's company got closer, the U.S. forces continued to fire.

"Our boys were getting hit right and left, and I couldn't keep up," he recalled

He said that he saw four members of his company in a crater protecting themselves from the artillery, so Trujillo ran to them. A couple of the men had been hit, and he was able to bandage them up as best he could. But behind him, he recalled, a soldier yelled his name. He didn't yell "medic," but instead called him by name. As Trujillo turned to help that man, the crater sheltering the four men took a direct hit.

"I didn't look back, I went to the other man that called me," Trujillo said. The young man had been hit in the back, and Trujillo could see a large hole.

"I knew I couldn't do anything for him, except try to make him comfortable," Trujillo said. "And I did. I made him comfortable, and I put him to sleep. And I don't know whether I did the wrong thing or the right thing. But as little as I knew about injuries, which was nothing compared to a doctor, I thought that as much as I could see in the dark, I could see that he was gone."

About that time, the company was able to identify itself for the Americans, and the shelling stopped, he said.

When Trujillo returned to the American side, he recalled that a captain told his medic to bring Trujillo over to him. A confused Trujillo followed the medic and was given two barbiturate pills known as "Blue 88s." In about five minutes, he was asleep.

The next day, Trujillo asked the medic why he had been pulled aside and was told that the captain had not wanted him to see the field jacket that Trujillo had been wearing. The front apparently had been covered with blood and bits of human remains.

Trujillo's second battle occurred when Company C went deeper into Germany. They arrived at the town of Remagen, which is south of Bonn, on the west bank of the Rhine River. The day before, Army engineers had removed explosives that the Germans had placed on the bridge that crossed over the river.

"When we got to the entrance to the bridge, we saw that there was a deep hole about 15 feet deep and 15 feet wide," Trujillo recalled. "We had to climb up to enter the bridge and run across it while being shelled by the Germans.

"We had to use extra caution when crossing on the railroad ties because there was nothing below us but the river and the water was very high," he said. "The river seemed to be as wide as the Mississippi River in the U.S.A., but I made it across."

After crossing the Rhine, the soldiers of Company D came under attack by what Trujillo believed was a tank, as they arrived in a farm village. He suddenly found himself on the ground, bleeding. He said that he reached inside his bag and gave himself a shot of morphine, and after about half an hour, another medic from the aid station arrived.

"I was taken to the aid station and met by Captain Bauer and our chaplain," he said. "The captain checked me over and gave me a shot of whiskey they called 'Purple Heart medicine.' When I used to come to the aid station for my medical supplies before my injury, the captain and chaplain would give me some 'Purple Heart medicine' before I returned back to the front."

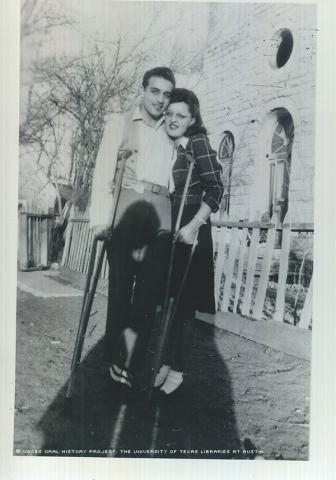

A piece of shrapnel had punctured an artery in Trujillo's leg, and the lower part of the limb had to be amputated. Trujillo underwent a surgery in France, and then two more in England, before being sent home on the same SS Argentina, which by that point had been converted into a hospital ship.

"After arriving in the U.S., I was sent by a hospital train to Beaumont General [Hospital] in El Paso, Texas," he said. "I was there for a year."

Trujillo later returned to his home in Watrous. For his service, he received several medals and awards, including the Purple Heart, which was pinned to his pillow during his treatment in England. But he said that the one that meant the most to him was his Combat Medical Badge, which is awarded for service while in the thick of battle. "That is the one I am most proud of..." he said. "I was able to serve six months on the front lines."

After being discharged at the rank of Tec 5, Trujillo moved to Denver, where he married Louise Archuleta on Oct. 12, 1946, and he also became a jeweler. The Trujillos had two sons, a daughter and several grandchildren.

Mr. Trujillo was interviewed by Joseph Padilla in Denver on Feb. 19, 2011.