By Betsy Clickman

Antonio Campos has devoted his life to fighting for the advancement of Latinos, engaging in civil rights work that has given Hispanics in South Texas a "head start."

As a child, having to share a bed with siblings or use a community bathroom facility wasn’t out of the ordinary for Campos, who grew up poor in segregated Baytown, Texas. His home was literally across the railroad tracks from the Anglos, a division that would fuel Campos' pursuit of equality throughout his life.

"In the restaurants . . . if you wanted to get fed, you had to go in the back. Mexicans and dogs were in the back," Campos said. "You had to get a sandwich and go home."

He watched in awe as Anglo Boy Scouts had fun building bridges and tying ropes, organized activities that for him were out of reach, for this was a time when the Scouts would never accept a Latino as a member. To participate, Campos formed a separate Hispanic troop. Even though they had to wear secondhand uniforms, the newly formed troop was determined to outperform its Anglo counterparts in a variety of Boy Scout events.

"We showed them that we were able to produce and be the leaders of the community," Campos said. Eventually, he was proud to become one of the first Latinos in Baytown to earn the designation of Eagle Scout.

Campos was first exposed to the war effort in high school, playing USO dances with his 14-member, Hispanic jazz band, an outgrowth of repeated rejections by the all-Anglo school band.

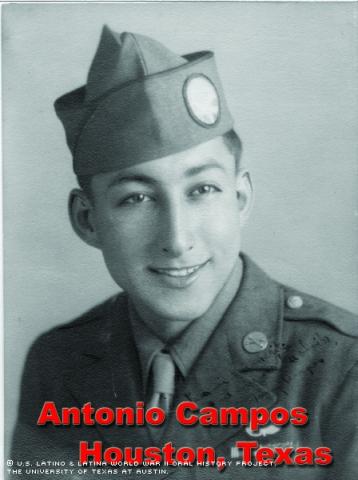

Just 22 days after Campos' graduation from Robert E. Lee High School, Uncle Sam called upon him to join the U.S. Army. Having failed the U.S. Air Force exam, he entered the Army as part of the 460th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion (75-mm pack howitzer), training at jump school at Camp Mackall, N.C.

"My position was to handle the .30-caliber . . . and .50-caliber machine guns," said Campos, who attained the rank of Private First Class.

His first jump was across enemy lines in Southern France on August 15, 1944, as part of the Anglo-American 1st Airborne Task Force.

"We must have lost half of our battalion in [that] jump," he said. "You start falling from the airplane and they start shooting and you could just look and hope that they don't hit you."

Campos attended Baylor University after his honorable discharge in October of 1945. He studied Mexican culture before completing his graduate work in law.

"I was lucky to have the GI Bill and [the Army] pay for it," he said.

During his first year in college, he married his high school sweetheart, Alicia Torres, and brought her to Waco, Texas. Their first daughter was born there, followed by three more children: one girl and two boys. Now grown, his children are Sylvia Angelina de la Fuente, Michael Anthony Campos, Aida Antonietta Garza and Marc Anthony Campos.

Campos eventually earned a Bachelor's Degree from Baylor in 1950. For 10 months, he also attended Baylor Law School. After college, he was employed by the U.S. Department of Labor. Working for the agency, he helped ensure that farmers who contracted labor from Mexico were fulfilling medical, housing and payment requirements.

"I had to make sure they weren't discriminated against," he said of the migrant workers.

Campos then developed an interest in teaching and began formulating a pre-school program for non-English speakers. He was commissioned to find a means for preparing young Latinos for success beginning in the first grade.

Toward that end, Campos solicited Baytown schools for a list of 400 English words to be used in the first grade. After implementing this vocabulary list, teachers saw tremendous improvement in Hispanic children's academic performance, Campos said.

As a result of his effort, "The Schools of the 400," adopted as Bill 151 by the State Legislature, provided mandatory pre-school programs for non-English speaking children getting ready for school.

"Everyone remembers the 'School of the 400' and ... that it later became the Head Start Program," Campos said.

During his battles for educational equality, Campos ran for mayor of Baytown. Defeated, he ran again four years later for City Council but lost again. Though he was active in the community, he never won a political seat. Campos attributes these losses partially to Baytown's failure to acknowledge a Latino candidate: In a city that elected government officials on an at-large basis, as opposed to single-member districts, it was difficult for a Hispanic to win the popular vote, he believes.

Undeterred, he pursued a Master's Degree in education from the University of Houston in 1974. About 10 years later, he found himself embroiled in the fight for Latino political representation in Baytown by petitioning for single-member districts. Although he’d failed to gain political office himself, he was determined to equal the playing field for other Hispanics.

"One day we went over to the city council to explain [what we wanted], and one councilman said, 'If you don't like it, why don't you go back to Mexico?’" Campos recalled. "I got up and said, ‘Hey! I was born here in Texas. I went overseas and put my life on the line so you people can make decisions like that?’"

As part of his fight for single-member districts, Campos worked hard to change the city charter. His protracted fight for equity ultimately reached the Supreme Court of the United States well into the '80s.

"The city spent more than $300,000 fighting me," he said. Finally, the Supreme Court upheld an appellate court decision ruling that the at-large election system violated the Voting Rights Act.

Once the charter was changed, Latinos quickly ascended to political offices in local elections, including those of mayor and councilman. Campos still spends time helping candidates get elected, as well as registering voters. He’s president of Campos Communications, a consulting company for political candidates.

"We have at the present time an opportunity to elect good leaders, and it all depends on us," he said. "Can we unite? Can we see the difference between good and evil? It is in our hands, we have the vote ... can we use it wisely?"

Campos feels the future bodes well for Hispanics, and he said he will make every effort possible to provide the education necessary to prove their abilities to lead society. In no small measure, the prevalence of Latino representation today can be credited to the results of his fighting for better education and stronger group initiative. Campos’ years of hard work have paid off generously.

His pride in having fought two wars -- one a global conflict another a social one -- is palpable.

Indeed, Campos is no stranger to fighting the good fight.

"Success only comes if you work hard at it," he said. And only when a fight is altruistic, with no personal agendas or ulterior motive, can success be deemed a foregone conclusion: "There's nothing that I have to hide."

Mr. Campos was interviewed in Houston, Texas, on March 2, 2002, by Veronica Garza.