By Juliana A Torres

William R. Ornelas grew up in a family of seven brothers and two sisters in Brownwood, Texas. They worked in the fields picking cotton, corn and wheat.

Like the rest of the country, the Ornelases were hit hard by the Depression.

"The whole world came to a stop. And so of course food and clothing were more important than school," Ornelas recalled.

To better help his family's financial situation, Ornelas dropped out in the 7th grade.

"I remember when I quit school, I knew that I wasn't going back to school," he said, explaining that the day was one of his saddest. "It was not necessary ... The first opportunity you had to work you would, because you were always poor."

All seven brothers would end up in the Army during World War II. In March of 1943, Ornelas' turn came. He was trained first as a medic, and went through basic training at Camp Grant near Rockford, Ill. It was snowing when the train first dropped them off in April.

"I was used to hard work so I went through it real easy. We used to go march 30 miles a day with a full pack," Ornelas said. "It's hard on people that never did things like that."

Though he thought the hands-on medical training was interesting, Ornelas really wanted to be part of the cavalry, as he’d seen in the 36th Divison before he left home. He settled instead for a position among the paratroopers of the 101st Airborne Division, volunteering for the opportunity after graduating medical training. He was immediately shipped overseas and joined up with the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment; however, he received his paratrooper training, a.k.a. jump school, only after they reached England in September of 1943.

The 101st Airborne Division, named the Screaming Eagles, played a decisive role in the war. Their first offensive began the D-Day invasions in the Battle of Normandy, as they landed the night before to secure the roads leading out of Utah Beach. Afterwards, the division was instrumental in capturing nearby Carentan, France, vital to defending it. In late June, the 506th PIR were withdrawn from the front lines and sailed back to England.

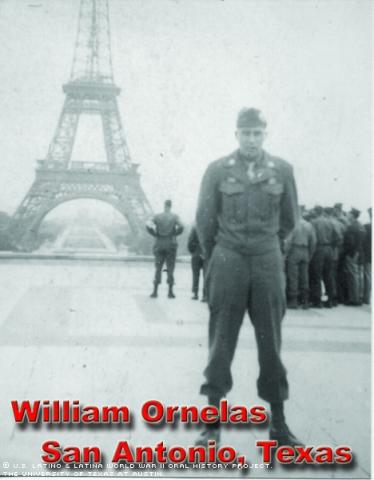

On Sept. 7, 1944, the 506th PIR parachuted into Zon, Netherlands, and fought in the Netherlands with the division until they were withdrawn to Camp Mourmelon le Grand, France. There they were allowed to rest and some, including Ornelas, were given a pass for leave in Paris.

Less than three weeks later, the 101st Division was rushed in trucks to reinforce troops in the Ardennes Offensive. They ended up stranded in Bastagne, Belgium, holding out for eight days against the German siege of the city, until Ally troops broke through on Dec. 26, 1944. Later, their heroic efforts would earn them a Presidential Unit Citation, the first time such an honor was bestowed on an entire division.

In January, the division assisted in the Battle of the Bulge, the Alsace-Lorraine front and a battle along the Rhine River. The 506th PIR liberated a concentration camp near Landsberg, Germany, and was one of the first groups of Ally forces to enter Hitler's Berghof and Eagle's Nest homes.

Ornelas learned early on that life in the military meant you had to fend for yourself, even when the situation was unfair. In one particular incident on base in England, a radish dropped off his tray while he was being served supper and a sergeant yelled at him for it. The conflict escalated into almost a fight before Ornelas picked up the dropped food, as he had been meaning to do at the beginning. He was given a week of sleeping in a tent as punishment, but attended a dance on the second night anyway. No one turned him in.

"You get kicked around but then sometimes you get a lot of breaks, too," he said. "You know, it all depends on how you handle yourself."

Ornelas was even offered a promotion he turned down, not wanting to deal with troops who wouldn't obey orders. Generally, he got along well with his comrades in arms.

"It is a lot of people from all over with different ways of thinking," he said. "You learned that you have to get along with people, and you'd be surprised how nice people are."

Often, Ornelas would loan his friends money. All but one paid him back, and he had plenty since he wasn't enthusiastic about spending money or gambling during his time overseas.

"All I wanted to do was come home. Get it over with and get back," he said.

After the war, Ornelas went to work on a ranch, fixing fences and putting out bales of hay and alfalfa. For a while, he worked in the fields as he’d done before the war, finally ending up with the railroad, where he made enough money to be able to marry Carmen Benavides.

Ornelas eventually decided, however, that the hard work and high frequency of injuries that came with the heavy equipment he was dealing with wasn't worth it.

"I decided, one day, that there was no future in that," he said.

The GI Bill allowed him to attend the Brown County Vocational School, where he learned welding, woodworking and how to read blueprints. With his new skills, Ornelas went to work for Canadair, an aircraft company that became part of General Dynamics in 1952. For three years, he made parts for the aircraft and earned more than twice as much as he had at past jobs.

When the Korean War ended in 1953, Ornelas was laid off. He worked for a construction company until he was rehired by General Dynamics to work on a Boeing B-52 bomber in Kansas before moving to Tulsa, Okla.

When a job opened up at the International Airport in San Antonio, Ornelas moved the family -- which now included four children -- back to Texas in 1957.

"My wife was ready to come home," he said, recalling that in Tulsa, people often assumed he was Native American rather than Mexican American.

Later, he would join the reserves to work at Kelly Air Force Base, and serve in Vietnam for three months at the end of the conflict.

His career as an aircraft mechanic was as varied as it was thorough. Though he never dealt with the electrical work, Ornelas' resume includes work with a "special weapons" division and -- just before retiring -- Navy rescue helicopters.

"I worked on a lot of aircraft," he said. "I learned about an airplane from wing to wing, from the front to the rear. Anything they wanted, it could be done."

Ornelas and Carmen have five children -- Rodolfo, Suzanne, Samuel, Jimmy and Deborah Ann -- and many grandchildren.

He says the greatest thing WWII gave him was use of the GI Bill.

"Life did change anyway for a lot of people, but that helped a lot more. Because eventually I made more money and worked all the hours I wanted," he said.

Mr. Ornelas was interviewed in San Antonio, Texas, on August 25, 1999, by Maggie Rivas Rodriguez.