By Kim Loop

Sisters Wilhelmina Cooremans Vasquez, 79, and Delfina Cooremans Baladez, 81, have done nearly everything together throughout their lives, including joining the workforce during World War II.

In early 1942, when the United States was mobilizing to join the war in Europe and the Pacific, the two sisters were eager to help.

When the older sister, Baladez, applied to join the civil service, her typing test score was in the top three in her area and she was selected to work for the federal government in Washington, D.C. But her father, a native of the Netherlands who’d immigrated to Mexico as a teenager, wouldn’t let her go. Johannes “Juan” Cooremans feared for his daughter’s safety alone in a new city. He told her “powerful men would take advantage” of her, Baladez recalled.

Out of obedience to her father, Baladez, then 18, turned down the Washington job. Both sisters did, however, drop out of San Antonio Technical and Vocational High School and take jobs at Kelly Air Force Base in their hometown of San Antonio.

Baladez’s primary task was to balance propellers. This was an important job, she says, because if the propellers weren’t balanced, the vibration could throw the airplane off course or even cause it to crash. Vasquez’s first assignment was to check to see whether all of the cracks in airplane components had been sealed.

“Then I went to the fuel-cell department and we would repair the deicers on the airplane,” she said.

The sisters recall the guys viewing them as a nuisance when they began working at Kelly.

“The men were more resistant because it was something so new. It’d never happened before,” said Vasquez, adding that, later, it got easier to get along.

Baladez was recruited by Boeing in 1945 to work at its Seattle, Wash., plant. Vasquez wasn’t allowed to go initially because of her age; however, she cried and cried when her older sister left, until her mother, Ofilia Cruz Cooremans, let her move to Seattle, too.

The Cooremans sisters left San Antonio for three reasons: the Boeing job paid better, they felt it was their patriotic duty and, for two young women who’d been “cloistered” their whole lives, it was an adventure. They rented a room in the home of a married couple, but say they lived as they would have had they still been residing with their parents.

“We valued ourselves,” Vasquez said.

The workplace also seemed more welcoming; the men less hostile.

“By the time we got to Boeing, they [men] were more used to it, the war was really going. They gave us work that was too delicate for their hands,” Vasquez said. “It was more grown-up work.”

The sisters sent home all of their earnings, keeping only enough for rent and groceries.

“That’s what you did during that time,” Vasquez said.

The war ended in Europe on May 8, 1945, and the two were sent home.

“I mean, we were told, ‘Go away little girl,’” Vasquez said.

“But not right away,” Baladez added.

The sisters traveled back to San Antonio less than three months later.

Although they’d taken the train to Washington state, getting back home proved more difficult: Train reservations were necessary, but didn’t guarantee travel, as military men were given preference. They ended up taking a bus home.

Although it was a joyous time because the men were returning, the transition to post-war life was difficult.

“They expected women to go back to their rightful place – go back to the kitchen, go back to whatever,” Vasquez explained.

They returned to the old ways, but they’d changed.

The experience “made me more independent,” Baladez said. “When we got back, we didn’t expect anything from our parents. I mean, we helped our parents, not expected them to help us.”

The sisters say that when they were growing up, they drew much of their strength from the strong example set by their mother, who was a Mexican immigrant. Their father moved to Mexico from Holland in 1903 at age 17, to avoid becoming a priest as his mother wished. In 1909, he married Ofilia, who was 14 at the time.

Juan worked for an oil refinery and managed a cattle ranch in Mexico. After disruptions in the oil industry caused by the Mexican Revolution, however, he was out of a job. He was also told he couldn’t own land solely in his name unless he became a Mexican citizen, which he didn’t want to do, wrote Vasquez after her interview.

“[T]hings had been getting dangerous politically,” and “My mother wanted to be closer to friends and [a] madrina in San Antonio,” Vasquez wrote. So in 1926, Juan moved Ofilia, along with Delfina and the Cooremans’ other four children at the time, to McAllen, Texas, slightly north of the Mexican border state of Tamaulipas. Vasquez was born four months later on Nov. 11, 1926.

Because he was a Dutch citizen and would have had difficulty immigrating legally through Mexico, as, according to Vasquez, Ofilia had done, Juan moved to Canada to establish residence there and then immigrate to the U.S.

Ofilia was left alone for several years with five children, in a country where she didn’t speak the language or know the customs. Contrary to the typical immigration pattern of family members in the U.S. sending money to relatives back in the homeland, Cooremans’ cousin cared for the cattle back in Mexico and sent the family in McAllen the money.

But one day the Cooremanses got a letter saying all the cows had died. On top of that, “Income from Mexico stopped when Papa left Mexico and could not control income from properties owned jointly with a Mexican citizen,” Vasquez wrote.

So with her husband far away, Ofilia, who “hadn’t worked a day in her life and was used to being provided for,” moved the children to San Antonio in 1928 and got a job, Baladez said. The family stayed in an apartment across the street from the red light district, where prostitutes would literally turn on red lights to invite men to their homes.

Unbeknownst to their mother, Vasquez, who was only a toddler at the time, would sometimes “wander away from my big sisters and my brother and they would finally find me socializing where I was not supposed to be,” wrote Vasquez of visiting her across-the-street neighbors. “They would find me being pampered, crimped and rouged[,] but they did not dare tell Mama because they would be in more trouble than I.”

Once, when the light bulb in their two-room apartment went out, Ofilia installed a red bulb as a replacement, unaware of its significance, Baladez recalls. When the landlady told Ofilia what it meant, she immediately took the bulb out and the family lived in the dark for a night.

“That’s how naïve we were,” Baladez said. “We were not prepared for what we had to go through, but my mother was bound and determined to hang in there until daddy got back.”

Juan “was able to emigrate from Canada legally into the U.S. in about late 1928 or early 1929,” Vasquez wrote. “[H]e moved us out of that neighborhood to a large house on San Luis Street[,] almost in the heart of what was then San Antonio.”

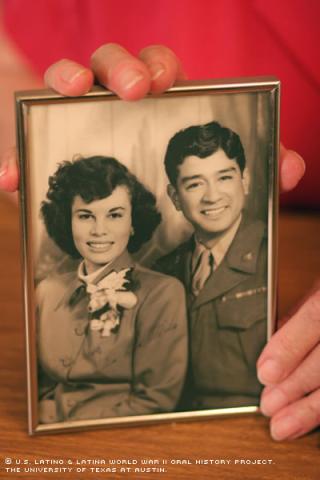

On Jan. 16, 1946, Wilhelmina Cooremans married Refugio “Mike” Vasquez, a native of Laredo, Texas. Mike had served in the Civilian Conservation Corps for 18 months, and then served for two tours of duty – nearly four years – with the 756th Tank Battalion in Italy, Northern Africa and Central Europe. He died in 1991 of a heart attack, due to complications from Diabetes. The couple had two sons, Michael and René.

“This should have been Mike’s story,” Vasquez wrote on her pre-interview form.

Mrs. Vasquez and Mrs. Baladez were interviewed in San Antonio, Texas, on July 9, 2005, by Brenda Sendejo.