By David Vauthrin

In October of 1945, Virginia Tellez Ramirez was at work at Levy's Department Store in downtown Tucson, Ariz., when she got some important news: Her brother Henry, who was captured at Corregidor in the Philippines, was alive and had returned home from World War II.

"I was at work downtown, and my brother called me at the phone over at the store and I couldn't believe it," Ramirez said. "It was like talking to somebody from the dead."

Ramirez says she told the supervisor on duty about the phone call from her brother, and he told her to go home and take the rest of the day off.

When she arrived home, she saw all of her relatives and neighbors dancing and having a great time in the living room, as a small band of three or four people played music for the crowd. She says her mother was the happiest of them all because she hadn’t known where Henry was for more than a year.

"They [the Army] reported him missing in action," Ramirez said. "My mother didn't know if he was dead or alive until they found out he was a prisoner of war."

Henry, one of two siblings in the military -- Ramirez's oldest brother, Trinidad Tellez, was also in the Army, stationed in Fort Levis, Wash. -- had kept his decision to enlist a secret from his mother. She only found out when she received a letter stating that Henry was stationed at Fort Bliss, a U.S. Army post in El Paso, Texas.

"He said he was going downtown with a friend of his, and they both went and enlisted," Ramirez said. "He didn't want to tell my mother, you know, what he was going to do."

Significant changes occurred on the home front while Henry was overseas fighting in the war, one of the most notable being the use of rationing books to buy food and certain supplies, such as shoes, Ramirez says.

"I remember we had the ration books," she said. "Each person in the family would get this book of stamps ... for your shoes, for your sugar, for meat, for the tires for the car. Those things I remember."

Rationing, a system of allotting scarce goods and services on the basis of national need, began in the United States a few days after the bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese. The Office of Price Administration, a federal government agency established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt shortly before WWII, regulated the rationing, which began with a freeze on the sale of automobile tires, and soon expanded to include meat, shoes, sugar and other household items.

The other drastic change Ramirez remembers from WWII occurred at Kress's dime store, where she worked: After Pearl Harbor, she says she and the other employees were told to clear all the shelves of Japanese goods.

"When they had Pearl Harbor strike, I remember they had us take everything off the counters that came from Japan. So that left the counters almost bare because everything at that time before the holidays was from Japan, you know," Ramirez said.

Other than the bombing of Pearl Harbor, such actions at stores and shops around the country took place because of two important declarations from Congress concerning relations with Japan in the months leading up to the U.S.’ entry into WWII:

The first was a formal embargo of iron and steel scrap on Sept. 26, 1940, preventing the U.S. from sending the Japanese any iron and steel Japan could use in combat against the U.S., considering the probability of war.

Then, two days after Japanese troops occupied French Indochina on July 24, 1941, Roosevelt froze all Japanese assets in the U.S., meaning the U.S. wouldn’t send Japan any valuable resources, mainly oil.

Ramirez says even though there was much work to be done at the dime store, her primary responsibility during wartime was helping her mother out around the house.

"My brother [Marcus Tellez] had two daughters from his ex-wife, and my mother was raising them, so I used to help her with the girls," Ramirez said. "You know, take care of them, bathe them, and get them ready for school, and things like that. I had plenty to do around the house."

It was about this time that Ramirez learned how to make flour tortillas from her mother, who made them for every meal.

Her mother eventually passed away in 1957, as did her father in 1959, but Ramirez says her mother lives on in her when she makes homemade tortillas, just like her mother taught her how to do as a young woman.

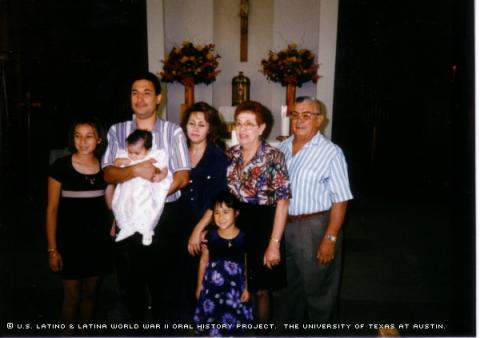

Ramirez met her husband, Guadalupe Ramirez, at a club in August of 1952, and the two married Oct. 11, 1952. They adopted two children: Henry and Joseph.

She now lives in Tucson with Guadalupe and spends her time caring for her three granddaughters; Bridgette, Brittney and Brianna; as well as cooking traditional Mexican dishes, such as salsa, tamales and, of course, tortillas.

Mrs. Ramirez was interviewed in Tucson, Arizona, on January 5, 2003, by Violeta Dominguez.