By Emily Macrander

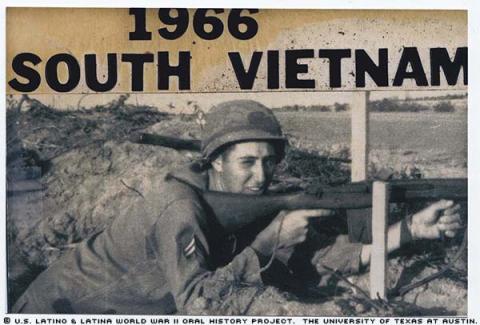

As his personnel carrier (PC) drove along a rice field in 1966, Vidal Rubio snapped a photo of the convoy. It was a rare moment of quiet for him in the hectic early years of the Vietnam War.

Suddenly, the tenth vehicle in the line hit a landmine.

Rubio and the other men in his truck were thrown from their seats. The men wondered: Who was hit? How badly damaged were the PCs?

Medical personnel were in the armored personnel carrier that hit the landmine. The explosion was so powerful that it threw the PC onto the PC behind it.

“The driver and gunner were found in parts because the explosion was right there,” Rubio said. “From that point, all of the paramedics were out.”

After the explosion that day beside the rice field, the platoon waited for help. The platoon gathered beside the PCs and assessed the damage. A Vietnamese man dressed in black darted from the brush. One of the men yelled, “VC!” The man was shot down with a 50-caliber machine gun.

“They pretty well suspected that he was the one waiting to push the button when the paramedics’ [armored personnel carrier] was hit,” Rubio said. “When we got out [to the Vietnamese man] he had a hole, just a little hole, in the back of his head. His whole face was gone. The 50-caliber that entered him just blew him out.”

One U.S. soldier removed the 25th Infantry Division patch from his uniform and put it on the chest of the dead man – his way of informing the enemy who had killed this man. After that, the soldiers walked away.

Rubio was born on Feb. 16, 1944, in Goliad, Texas, about 90 miles southeast of San Antonio. His parents, Catarino Rubio and Pola Cortines Rubio, worked on ranches. Rubio had two older sisters and two younger sisters. He enjoyed hunting and fishing. He was accomplished in sports -- he ran track and was a three-year letter man in basketball.

After he graduated from Goliad High School in June 1963 he looked for a job. After two unsuccessful weeks, Rubio went to the Goliad courthouse, met with an Army recruiter, and signed up. The recruiter told Rubio to return at the end of the week. He would then take a bus into San Antonio to complete his enlistment forms.

What seemed to be an easy solution to a fruitless job hunt would fundamentally transform Rubio’s life.

Rubio remembered waiting for his combat deployment, especially in the years before the Vietnam War. When he enlisted, he said, he had never heard of Vietnam. He soon found himself on a ship in the Pacific, headed west.

“We had our orders and everything, but no one knew where we were going,” Rubio said. “Rumors were that we were going to Korea. On Nov. 22, 1963 … the [ship’s] captain announced that [President John F. Kennedy] was killed in Dallas. He said that we were going to pick up steam, and that we were going to land in Pearl Harbor.”

When Rubio arrived in Hawaii, he and the other men from his ship were taken by truck to Schofield Barracks. He was assigned to Co. B, 3rd Platoon, 2nd Battalion, 14th Infantry Regiment, 25th Infantry Division.

The company prepared a parade to honor the president, Rubio remembered. A sergeant walked up to him and demanded to know why Rubio wasn’t wearing his proper collar insignia. “I said, ‘Sergeant, I have none. I just got here,’ and a voice said, ‘Sergeant, I have extras. He can use them.’ ” The voice belonged to Bronx native Gary Schmeltzer, and he and Rubio quickly became friends.

“[In] January of 1964, I was told that I would be going to the big island of Hawaii,” Rubio said. “We were going to be training over there for a month. Gary explained, ‘Well … you have two volcanoes. You have Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea. The camp is Pohakuloa. Everywhere as far as anywhere you step is nothing but lava. The first thing you do when you come back [to the Schofield Barracks] is get a new pair of boots because your boots are going to be all cut up, and they’re ready to be thrown in the trash.’ ”

Rubio trained in Hawaii for 25 months and went through several pairs of boots. He said the weather was nice: cold at night, warm during the day and, for the most part, dry. He listened to Schmeltzer’s advice. Schmeltzer was soon re-assigned, Rubio recalled, and he left Hawaii in February 1965.

After completing his training in Hawaii, Rubio was sent to Okinawa in February 1964, where it rained all the time, he remembered. Men were stationed there for rapid deployment to any trouble spots in the region. But there was some leisure time too. Servicemen not occupied with training for jungle warfare relished a new kind of music.

“Someone had a transistor radio and said, ‘There’s this new group from England, and they’re tearing everything up with music.’ It was the Beatles, and they were just getting started,” Rubio said. “All of the stations that you would put on you would hear Beatles songs.”

On March 14, 1964, Rubio was promoted to private first class. He enjoyed the training, which he found rigorous but exciting. And he found a new snack food.

“While we were out there playing ‘Cowboys and Indians,’ there were bananas all over the place,” Rubio said, smiling. “I ate so many bananas that by the time I go back to Hawaii, I did not eat a banana for a long, long time.”

Rubio and his colleagues still weren’t quite sure where they’d end up. In June of 1964, the military began taking volunteers to pursue military action in a country no one knew anything about.

“Of course no one had ever heard of Vietnam,” Rubio said. “No one knew what was going on but they said that there was a war going on somewhere in Vietnam. They were asking for volunteers to go for six months as shotgun riders on the helicopters. The incentive was combat pay.”

Some men from his company went. Rubio stayed behind. When the men returned, they told Rubio and other soldiers that they had been deployed to support the South Vietnamese military. They told stories of being roused from bed in the middle of the night to participate in military operations. In general, morale among U.S. forces in Vietnam was high, and many men volunteered to return.

On Jan. 26, 1965, Rubio was promoted to the rank of specialist. He remembered that his primary weapon was an M79 grenade launcher.

Before his combat deployment, Rubio was allowed a short trip home. In May 1965, Rubio got a “hop” on an Air Force plane to the U.S., followed by a series bus rides to San Antonio. But when he arrived at the last bus station, he had a problem: He was 92 miles away from the ranch where his parents worked, and there was nobody at the station to meet him.

But by a remarkable coincidence, he ran into his cousin, Joe Flores, at the station, and he offered Rubio a ride home. Rubio wrote later that his cousin was “just passing by.”

Rubio returned to Hawaii once his leave ended. He returned to rumors that the 25th Division was headed for Vietnam.

On Dec. 26, 1965, Rubio was called to a morning battalion meeting.

“The colonel gets on the speaker and he says, ‘Gentlemen, I have some good news and some bad news for you. If you are [ranked at] an E4 [pay grade] and below, you are going to be sent to other companies as replacements, and next month you will be headed to Vietnam. If you’re an E5 or above, you will be receiving new recruits, and you will be training them.”

Spc. Rubio was ranked at E4, so he knew he would be packing his bags for Vietnam. However, right before he was sent out, Rubio and five other men were promoted to corporals.

Rubio was re-assigned to Co. A, 2nd Platoon, 1st Battalion, 5th Mechanized Infantry, 25th Infantry Division. When Rubio arrived at his new assignment, he had adjustments to make. He had the weight of a higher rank and new authority over men he was just meeting. He also worried that he might be treated differently because of his race.

“I remember that when I walked in with my duffle bag, I looked around and it was nothing but white GIs,” Rubio said. “And here I am Hispanic with all of these white guys. I [asked] myself, ‘What did you get into?’ ”

A sergeant assigned Rubio a bed and told him to wait for his team, which would also be coming in from different companies.

“Everyone was fine,” Rubio said. “They took me in even though I did not know anyone in the whole company. An hour later, two new white guys walk in. Thirty minutes later, two more white guys. Then, 30 minutes later they say, ‘Rubio, this is your last man.’ He was an Afro-American. I said, ‘Thank God,’ because we’re the only two oddballs in the entire platoon. From that day on, we were always together, me and him. His name was Hamilton, and he was from Chicago.”

On Jan. 5, 1966, the company boarded the USS Missouri and sailed to Vietnam. Off the Philippines, two submarines joined the ship as escorts. Rubio arrived in Vietnam on Jan. 20.

When the ship entered Cam Ranh Bay, Rubio recalled feeling surprised when he saw hundreds of ships and small boats.

Their first scheduled stop was to be the University of Saigon. The men looked forward to a tour of the campus. But what they saw there introduced them of the situation in Vietnam.

“When we got there, there were three buildings left and some wall,” Rubio said. “Everything had been bombed. [The commanding officers] went ahead and said, ‘OK,’ assigned us foxholes and said, ‘dig.’ ”

For many of the men, this was their first combat deployment.

“The first night in Vietnam, four or five foxholes to the right, someone opens fire with their M-16,” Rubio said. “Everybody hits the ground. What happened was the private that was in the foxhole that had been relieved got out and was going to relieve himself, but he walks in front … as he’s coming back … the new guy sees him and, [says] ‘Hey, he’s a [Viet Cong],’ so he opened fire on him and killed him.”

By the next morning the shooter had been removed from the unit and sent elsewhere.

The men moved into more dangerous regions of Vietnam. Rubio said there was fighting every day that would leave one or two men dead and three or four men wounded. U.S. forces rarely saw the enemy, Rubio said, and instead more often engaged in brief small-arms fights.

They were always on alert to any danger, Rubio remembered.

Rubio taught his men to walk at least 10 yards apart from each other during an operation or on patrol, essentially diffusing themselves as a potential target.

“One day, as we’re walking back to base camp, up ahead of the column at one point five men were walking together,” Rubio said. “I tell Sgt. McElroy. He says, ‘Oh, I hope nothing happens.’ Within five minutes there is a blast. POW! Everybody hits the ground. It was a claymore mine. Since the five of them were together, the captain and the point-man were killed, and the other three were wounded. If they had been spread out, maybe we would have lost [just] one.”

The next week, the men received a new captain. This captain informed the men that they would not be going back out into the field until they received personnel carriers. The PCs all followed the same track in an effort to escape landmines.

On Feb. 16, 1966, Rubio celebrated his 22nd birthday. “It had rained all night,” Rubio said. “I get up and I eat my scrambled eggs and I eat my pound cake and wish myself a happy birthday. I said, ‘Please let me get out of here in one piece.’

When his company returned from their operation that day, they reported 15 dead and 20 wounded.

Throughout Rubio’s tour of duty, his mother thought he was in Hawaii. At the time of his Vietnam deployment, his mother struggled with diabetes, and the family decided that she didn’t need the extra stress of knowing her son was in heightened danger. The rest of Rubio’s family knew and kept in touch through letters and occasional care packages, which included tortillas, nuts and sweets.

Rubio later remembered introducing his fellow soldiers to tortillas after receiving a care package and walking into his tent to open it. “Sitting right in front of me, on the wooden floor, were my four assigned GIs [along with five or six others], wanting to know what was in the package. I got one dozen tortillas and a dozen brownies. … I took two tortillas for myself [and] cut the rest in four pieces. You have to remember,” he added, “these guys did not know what a tortilla was. Each was given a piece, and they ate it.”

He remembered asking them if they wanted more. Everyone said yes. Also, “everybody got a piece of brownie.”

Rubio’s last operation took place in May 1966. His Army company had a policy that men with less than a month left to serve could perform duties around camp instead of going back out into the danger zones. His company deployed two more times before he went home.

On June 17, 1966, at the end of his tour, the captain spoke with Rubio and offered him a cigar. Rubio declined the cigar.

“[The captain said,] ‘Cpl. Rubio, I don’t know you, but your sergeant and your lieutenant say you’re a very good soldier. If you re-enlist, I will make you a buck sergeant,’ ” Rubio said.

Along with the promotion, he was offered a $3,000 bonus.

“I said, ‘Thank you very much, but I don’t think that sergeant stripes will help me in civilian life,’” Rubio said, covering his mouth to laugh.

When he returned home, Rubio went to the Chevy dealership and bought himself a new maroon 1966 Chevy Impala with the money he saved from the Army.

Rubio again struggled to find employment. He moved from Goliad to Houston, where he took a job with 7-Eleven as a store clerk. Rubio began welding on the side and hoped to earn enough money to go to welding school. His father offered to pay for school, so Rubio was able to earn his degree. In March 1966 he secured a welding job at Todd Shipyards in Houston, earning $3.09 an hour, a great increase over his previous salary of $1.95 an hour. He would work there until early 1975.

In December 1967, Rubio became engaged to Edulia Sanchez, and the couple was married on June 22, 1968.

Soon his wife became pregnant with a baby girl but she miscarried in April 1969, only one week before the due date. Rubio said it was possibly linked to aftereffects of his exposure to Agent Orange, the defoliant sprayed over Vietnam’s jungles and later blamed for various illnesses suffered by Vietnam veterans. The Rubio family buried the baby with the money that was meant to be her college fund. The couple tried again and miscarried again, this time in April 1973.

Rubio’s wife began working, and the couple was finally able to buy the house they wanted.

At work, Rubio began hearing rumors of a strike. He decided that it was time to change careers. He tapped the GI Bill in January 1975 and enrolled in the Houston Police Academy. He graduated in May 1975 and began a 30-year career. He retired in 2005 because of heart problems that he believes were also linked to Agent Orange.

He applied to federal veteran’s programs for assistance in 2007 and was accepted. When the VA treated him, Rubio found out for the first time that he had been exposed to Agent Orange. He said his health complications linked to the exposure included heart problems, diabetes, glaucoma and infertility. However, Rubio did not believe that all of his health issues were caused by his exposure to the defoliant.

After the war, Rubio experienced combat-related nightmares. He advised his wife not to wake him when he was having one of these dreams. As time passed, the nightmares became less frequent. Rubio said he was also diagnosed with major depression, though he said that he didn’t believe that diagnosis because he didn’t feel depressed. He added later that by 2010 he was diagnosed with an anxiety disorder.

Rubio kept in touch with the other veterans living in the city. He also kept in touch with Schmeltzer. In 1977, Rubio said, he and his wife spent some time with his old training buddy in the Bronx. The next year, Schmeltzer spent a week with them in Houston. Schmeltzer, Rubio said, died in 1981.

Rubio said he recently visited his cousin, also a veteran. As he thumbed through a book that listed Purple Heart recipients and their current addresses, he came across a name that he recognized: Larry Grant.

He remembered Grant. It was March 6, a few months before the end of Rubio’s tour of duty and his return home. Rubio said he was determined to make it home safely.

“I said, ‘Hey, sergeant, where is the safest place to be if you’re on patrol?’ He said, ‘Be the last guy.’ So on this particular time, headed back to the base, I’m in the rear. Ten yards ahead of me is Larry Grant, a machine gunner. We’re going along, and everybody is happy because we’re headed back to the base camp, and we’re going to have a good meal. So we’re going through a rubber plantation and all of the sudden we get ambushed. It’s like dat-da-ta-da-da,’ he said, referring to the sound of gunfire, “and then it’s over. We would never see anybody. As we hit the ground I hear Grant say, ‘I’ve been hit.’ So then I rush to him, and he’s been hit. He was taken to Saigon [along with the other 60-caliber machine gunner].

“Four weeks later, he’s back. From that point on, they put him on duty around the base,” Rubio said. “For some reason, I remember his name, his whole name.”

When he saw Grant’s name in the book, Rubio decided to write a letter to Grant. A week later he received a response. Grant replied, “Oh yes, Rubio, I remember you. You were the one who helped me. …” Rubio said he and Grant stay in touch.

Rubio and his wife live in Needville, Texas, with their two horses.

(Mr. Rubio was interviewed at the Immaculate Conception School in Goliad, Texas, on July 20, 2010, by Elizabeth Blancas.)