By Anna Zukowski

An award-winning sharpshooter, Valentino "Smokey" Cervantes dodged death as a member of the 801st Tank Destroyer Battalion.

On an M-1 Tracked Recovery Vehicle, Cervantes would pick up disabled half tracks after each battle. With a promotion to technician 5th class, he went on to see dogfights in which British fighter planes were shot down, "buzz bombs" flying toward England and damaged American bombers plummeting to earth. Once, a bomb even fell 20 yards away from Cervantes' vehicle, while his company was crossing the Roar River in Germany.

"We heard the whistling sound, but we couldn't move. We just had to wait until the bomb hit," 82-year-old Cervantes said. "That's the closest I ever came to getting hit."

The 801st Tank Destroyer Battalion landed at Normandy, France, with the 4th Infantry Division and fought the Battle of the Bulge with the 99th Infantry Division. The battalion later supported the 30th and 83rd Infantry divisions and ended the war with the 13th Armored Division.

Just over a decade earlier, Cervantes' life was happy and peaceful. He remembers the family's small home in Houston, which he shared with 11 siblings. Cervantes' memories of Depression-era Houston are of happy times with his family and schoolmates.

"My father bought us this little house, and we had to kind of share everything," Cervantes said. "My dad always managed to have food on the table and enough clothing for us. Of course, we had to do without certain things."

Everyone in the Cervantes household "pitched in," he recalled. "So we got on pretty good. "My dad was a real fine person -- religious." Cervantes remembers Sunday's mornings, putting on neatly pressed clothes and going to church. He also remembers fishing, dancing and picnics on the Galveston shore near Houston with his family.

Alfredo Cervantes, Cervantes' father, made sure all of his children received an education, which was an impressive feat in a time when most Latinos were steered away from school toward work. Ten of Cervantes' brothers and sisters received high school diplomas, including Cervantes. He remembers Sam Houston High School fondly.

"I liked school because we got to participate in sports and programs, like stage programs -- playing Indians and stuff like that," he said "I really enjoyed going to school because they had so many things to do."

The war effort interrupted Cervantes' life on Aug. 18, 1944, when he began training for the infantry. Already a graduate and working at a defense shipyard in Houston, he left behind a wife and two sons. Thirteen years later, William, a third son, would be born.

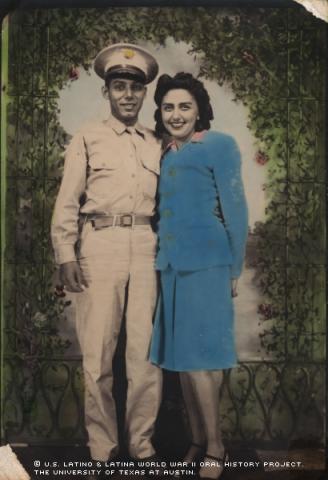

Cervantes met his wife, Rosemary Yramateguer Cervantes, at a nearby park, which was the stage for neighborhood dances together with another area park.

"So, they brought their group to our park to practice dancing and she became my partner," he said. The couple has been married for 61 years.

As a member of Headquarters, 801st TD Battalion in Germany, "I think I was the only Hispanic in the whole company," from among the group of more than 100, Cervantes said. Yet, he generally felt comfortable the entire time he was there.

"I had never been away from home before," Cervantes said. "So when I went to the service, I met such a bunch of nice guys that eventually I didn't miss home too much because we all worked together and it kept us busy.

"The commander, Captain Fabian, he treated the Hispanics just like anybody else.”

All told, Cervantes spent 13 months in Germany.

"It's terrible. War is not funny," he said. "They glorify it on TV, but it's not like that when you see your buddies all shot up; it's different. I saw a lot of dead soldiers; we would always move forward to different towns, and when we got there, the bodies were still on the ground, all shot up with arms missing," he said.

Cervantes said he didn’t feel lonely for loved ones because he was so involved in what he was doing, adding, "Of course, at night you do; when you go to bed, the only thing you go to bed with is a rifle.

"One thing (that was) outstanding, when we were crossing the Rhine River, I looked down and there was a friend of mine -- we grew up together -- guarding the pontoon bridge they had just built so we could cross, he said. "He went berserk; I thought he was going to fall in the river."

Cervantes said he still finds it inconceivable that having traveled that far, he found Roy Gomez, his childhood friend, guarding the Rhine River. The 801st was crossing the river near Wessel, at the time to protect the left (north) flank of the corps as it swept past the industrial Ruhr section and on to the Elbe River.

Cervantes earned Victory and campaign medals while overseas.

"The more bulls-eyes you hit the better you get; I got pretty good at it, so I won the Army Sharpshooter .45 Medal," said Cervantes, who was sent home in February of 1946.

"The war was a great experience," he said. "I wouldn't trade it for anything in the world, but I wouldn't want to do it again."

Cervantes added that the conflict also changed his perspective about the people around him.

"You think better of people. After seeing all of that, you change your attitude about people. You see the hate and why people kill each other, and when you come back, you have a different attitude about that. It makes you a better person," he said.

Mr. Cervantes was interviewed in Houston, Texas, on March 2, 2002, by Celina Moreno.