By Cindy Carcamo

U.S. Navy veteran Trino Soto can't remember the exact date or location, but the image of his ship along with eight other destroyers traveling in the evening along the Pacific Ocean will forever remain in his mind.

"As we were going I was looking back, like this, because we were the flag ship. And, they were all staggered, one behind the other like that," Soto said. "That was the most beautiful sight I ever saw -- those nine destroyers going full steam."

This is just one of countless memories Soto recalls as a former crewmember of the U.S.S. Haggard (DD-555) destroyer, which was awarded 12 battle stars during World War II.

Soto was with different task force groups during the Pacific naval campaigns. He operated with the 3rd Fleet, the 6th Fleet, Task Force 38 and 58 and the admirals 5th fleet. He fought in battles near Japan and the Philippines.

But, Soto's battles began long before the war -- as a child during the Great Depression. The 76-year-old Fresno, Calif., native, who was born to two Mexican parents, dropped out of school in the 10th grade and got a job as a shaker at a local fig orchard to help his family.

When WWII erupted, he joined many of his neighborhood playmates who went into the service.

"I was working in the Hotel Fresno and I remember somebody saying something about Pearl Harbor being bombed but I didn't know where Pearl Harbor was then," said Soto, who’d seldom traveled outside of Fresno. "That's when I decided I wanted to join; because the United States had gone into war and I was going to help defend my country."

He spent three months in Seattle, training and standing watch as the U.S.S. Haggard was being built. There he met George Phillips, his first good Navy buddy, who’d become a lifelong friend.

When the destroyer was finished, it headed out to the Marshall and Solomon Islands and other sites along the Pacific Ocean, where they fought in 13 major battles. They then spent three months in shakedown inspections off California and two more in squadron maneuvers off Hawaii. They left Pearl Harbor for combat operations on Jan. 22, 1944.

Soto remembers one of the worst battles took place at Okinawa on April 29, 1945. The Haggard navigated alongside the Battleship Missouri when the destroyers took off about five miles in front of the fleet to look out for enemy ships and planes. Just as the Haggard was to turn back and join the fleet, a kamikaze attacked the destroyer.

"We were by ourselves. And there was about five of them and two of them peeled out. One came really low over the water and the other one was coming straight down. The other one was heading for the bridge. And, this one, coming real low over the water was heading for mid ship," said Soto, swooping his hand like a plane in a dive.

Soto was on the starboard bow struggling to fire with his 40-millimeter director at a kamikaze flying near the starboard side of the destroyer.

"I couldn't fire on that sucker. But I was watching him. And, just before he hit the ship, he stood up on the cockpit," Soto said. "And then he rammed the ship. He hit her right on mid ship. Then the ship exploded. It killed everybody in the engine room -- no survivors there."

The ship began to sink. Soto figures the other Japanese planes stopped attacking after they saw it on fire and sinking.

The carriers heard the distress signals and soon U.S. planes shot down the remaining suicide planes and the Haggard kept afloat. Though the destroyer almost went down, Soto said he remained somewhat calm during the ordeal.

In general, he didn’t let his emotions get the best of him during the battles, he said, however, afterward was sometimes a different story. For example, he remembers having to deal with the loss of three sister ships during the The Battle of Leyte Gulf in October of 1944.

The Haggard and the other eight destroyers joined a fleet sent to guard the gulf while Marines landed to invade the Philippines. But Navy Admiral William Halsey took most of the fleet to chase some Japanese carriers, leaving nine destroyers to guard two carriers. It later turned out the carriers were merely decoys.

Soon after Admiral Halsey left with the Third Fleet, a large force of Japanese battleships and cruisers charged the American invasion site, defended by this light task force. Three destroyers were ordered to charge between the Japanese units, the remainder formed a security line in front of the carriers, which retired quickly to get out of battleship range and launched all their aircraft. The three destroyers, guns blazing, were shot out of the water; the security line looked to the Japanese like Halsey's battle screen and the aircraft were thought to be from Hasley's main fleet carriers. The Japanese charge faltered and they withdrew. At a cost of the destroyers Johnston, Hoel and Heermann, the U.S. averted what would have been its greatest naval defeat in the war, the total destruction of the Leyte Invasion force.

"The way we heard it, the Johnston was sinking -- they were all shot up. And she was sinking and they were still firing their guns at the enemy. And the Hoel, I think the Hoel only had 45 survivors, the Heermann -- I don't know," Soto said. "That was sad, because we used to tie up along these ships when we came into a port or something. So we used to kind of know those guys."

After the battle, the Haggard's skipper called Admiral Halsey to ask for permission to go back to pick up some survivors. He denied the request and ordered the Haggard to stay with the carriers, Soto said.

Years later, Soto was told most of the seamen from the destroyers had been killed by sharks.

"That even made it worse because we couldn't come over there and try to pick up the survivors," he said. "That made us real depressed to know that we had lost that many men. Our nine destroyers were one happy family. It was like sister ships."

He felt the closest to his own crewmembers on the Haggard, however.

"We slept together, we saw each other in the mess rooms everyday, in the bathrooms and so forth. There was no privacy,” said Soto with a hearty laugh. "On a ship there is no privacy."

Despite living in such cramped conditions, he said he got along very well with everyone on his boat.

Thanks to the war, however, Soto believes he and other Mexican Americans got the opportunity to advance in the U.S. Before the war, most Mexican Americans only had the option of labor work and, therefore, could only afford to rent, he said. Afterward, they had the chance to hold professional jobs and own homes, said Soto, who later became a business owner and built his own house.

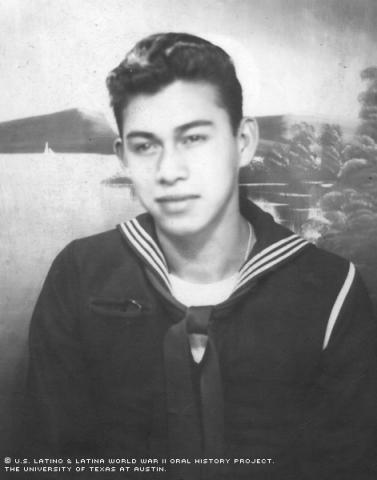

More than 50 years after the war ended, the veteran still considers his service on the USS Haggard an important time in his life. The hallways of his home stand decorated with old war photos of him and his Navy buddies in uniform, as well as souvenirs from the Haggard and WWII.

Mr. Soto was interviewed in Fresno, California, on May 4, 2001, by Cindy Carcamo.