By Sierra Brasher

Saragosa A. Garcia always marched to the beat of a different drum.

And his ability to play music, to change the tempo of his life, along with the assurance from carrying a treasured Holy Bible and his mother's prayers, may have helped him through tough times in World War II and in a segregated Texas.

Born Oct. 22, 1922, in Corpus Christi, Texas, to a family of musicians, Garcia says he was destined to play the drums.

He had six brothers and three sisters. His parents had a brand-new Model "T" Ford. His family moved to a small farm the family called El Rancho Colorado (The Red Ranch) in Rosenberg. His father, Flugencio, worked part-time as a carpenter in the area.

Garcia smiles as he reveals his father's other job title, "playing music."

And sometimes Flugencio had another sideline.

"I'll tell you this, he was a bootlegger. He sold whiskey," Garcia said.

He started school at Robert E. Lee Elementary in Rosenberg and had problems from the very beginning with his teacher, who was about 90 years old, he says.

"She didn't want us to play with the Bohemians -- you know, the white folks," he said.

The school was segregated, and his teacher wouldn't promote him to the next grade level at the same pace as the white students in his class. He remembers how the Latino students -- including his brothers and sisters -- learned how to dig holes with a shovel outside, instead of taking a recess. And while the Anglo children took their recess, the Hispanic children were in the classroom.

"I was in the third grade for three or four years," Garcia said.

His dad finally got fed up with the discrimination his kids received at school.

"My children didn't come here to learn how to dig holes," Garcia recalls Flugencio saying. He took the kids out of Robert E. Lee and moved the family to Houston to attend Jones School. In 1935, at age 13, Garcia finally passed to the fourth grade.

Garcia remembers a certain teacher he had, a Mrs. Smith, who gave him a Bible.

"I still have that Bible today," he said.

Shortly after they moved to Houston, Garcia's dad had a nail go through his hand and wasn’t able to work. The family moved again to Rosenberg to pick cotton on a farm for a month. Then they moved to town.

"I was the oldest, so I had to start working," he said.

He sold candy, delivered newspapers and worked at a fruit stand in Houston until he turned 20.

"I didn't want to go to school anymore," he said.

Along the way, Garcia discovered his love for playing the drums.

"I learned music from watching my brothers," he said.

In 1942, Garcia's entire life changed when he was drafted into the Army. He was sent to Fort Bliss in El Paso, for training with a crew of four other men to be anti-aircraft gunners. He remembers learning how to shoot at a moving target, and that it was difficult because if they missed the target, they could do some real damage, he says.

"If we shot too far off, we'd shoot the plane!" he recalled.

Garcia also participated in desert training in nearby Las Cruces, N.M.

"Sometimes, we took a week or two of infantry training in the desert -- with all the snakes," he said.

In 1943, his unit took an eight-day train ride to Camp Pickett in Virginia. Compared to the hot climate of El Paso, the weather in Virginia was almost unbearable.

"It was so cold there," he said.

As part of their training, they had to swim in frigid water.

"We would swim with no clothes. Nothing," Garcia said. "We were planning for D-day."

Shortly after celebrating New Year's of 1944 at Camp Kilmer, N.J., Garcia joined more than 15,000 troops on a ship to Europe.

"We went across the Hudson River and saw a big old ship with 20,000 soldiers on it," he said.

He boarded the Queen Elizabeth, the world's largest ship. Eight days later, on Jan. 8, it docked in Scotland.

British and American officials welcomed the troops aboard the ship. Garcia remembers hearing Bing Crosby sing "The Funny Old Hills." Nearby, women from the Red Cross served coffee, doughnuts, candy and cigarettes.

Once arriving in Scotland, they took a train to the south of England in preparation to cross the English Channel. On Feb. 20, 1944, Garcia was assigned to Battery B of the 197th Anti- Aircraft Artillery Automatic Weapons (AAA AW) Battalion (Self-Propelled), attached to support the 16th Infantry Regiment of the First Infantry Division. They trained in England until heading for Normandy's Omaha Beach.

June 6, 1944, the first day of the Normandy Invasion, Garcia's captain said, "This is the day you need to start praying."

Garcia came from a strong Pentecostal background, and he believes he has his faith to thank for his survival.

"I carried that Bible Mrs. Smith gave me on all the time," he said.

Garcia was in the second wave of American soldiers to land in Normandy.

"We were supposed to land after the combat engineers," he wrote after his interview. "So we had a hard time getting over the hill; we had to wait 'til the engineers make a road."

A sniper shot at me from a hill and just barely missed," he said. "And I was laying down and praying for some guy to make a road so we could get by."

His prayers were answered when an engineer cleared a road for them to cross.

"There were bodies all over the place and ships burning," Garcia said.

After his close encounter with death, Garcia saw action in France, Belgium, Luxembourg and Holland before entering Germany.

On Dec. 16, 1944, in eastern Belgium, Garcia heard a voice on the radio warn, "Everybody, get out of here now. The Germans are 10 miles away."

This marked the beginning of the Battle of the Bulge, which has been called the worst battle in history in terms of losses to American forces. More than a million men fought in the snow, and at least 19,000 Americans died.

One leader said to his men, "There are two types of people who will stay: the dead and those who are going to die."

Garcia was one of the lucky ones. He put his half-track into four-wheel drive and made it out of the battle with no wounds. He was with an antiaircraft artillery battery attached to the 16th Infantry Regiment. His unit, Battery B of the 197th AAA-AW Battalion (SP), protected the soldiers from the air, defending the quartermaster transporting ammunition to the front lines.

When the war ended, Garcia didn’t go home immediately. First, he had to guard a prisoner of war camp in Germany. He remembers one night when he was on guard by himself. His sergeant said, "Anybody who comes through here -- kill him."

Garcia heard footsteps early in the morning and he started shaking as he said, "Oh Lord, please help me." It turned out that it was just a group of people going to church. Once again, Garcia says he had his religion to thank: "The Lord helped me not to fire," he said.

Garcia was discharged in 1945, having earned the rank of Corporal. He also earned a EAME Campaign Medal with five Bronze Stars, a Victory Medal with one Bronze Arrowhead, a Sharp Shooter medal, a Half Track Medal (for being a driver) and a Good Conduct Medal.

He moved back to his home in Rosenburg, where he could resume life as it had been before the war. He combined his love of music with his faith by playing for his church, and even played the drums in a country-western band.

"We used to play all over the place" at parks, parties, weddings and hotels, said Garcia, adding, "I even played with a symphony. I didn't know how to read the music so I just followed signals.”

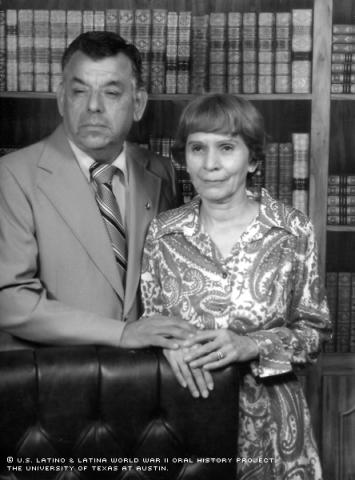

In 1952, he was married and moved to Houston, where he and his wife, Ophelia Turnini Garcia, still live today. They have two sons and a daughter.

Garcia later worked at a shipyard, where he says discrimination was apparent. His supervisor assigned him to "Mexican labor" and only gave the white workers the good jobs, he says, adding that they had separate facilities for the "whites," "colored" and "Mexicans."

Garcia sued the shipyard for discrimination and won. He says his action changed the way the company treated minorities, and the shipyard was forced to grant everyone equal facilities.

Deciding he wanted to do something more with his life, Garcia applied and was accepted for an automotive mechanic position with the U.S. Postal Service. While still playing music all over town with his band, he retired after 28 years with the Postal Service.

"My wife asked me, 'How in the hell did you do all this with only a fifth-grade education?'" Garcia said.

Mr. Garcia was interviewed in Houston, Texas, on November 18, 2002, by Ernest Eguia.