By Melissa Sellers

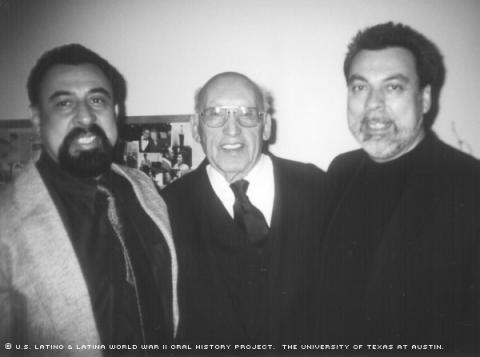

Clad in a stiffly starched khaki dress shirt and pants that tent over his thin frame, Santos Sandoval calmly recalls his experiences in the South Pacific Theater during World War II.

Now retired in Los Angeles, the 82-year-old Sandoval enlisted in an infantry regiment at 18 because "it sounded good." He’d go on to receive numerous awards for significant heroic deeds during his tour of duty.

As a youngster in the small farming community of Delta, Colo., with only a junior high school education, Sandoval could have never imagined the international adventures that awaited him. The second child in a family of five brothers and five sisters, he spent most of his childhood working on a farm. All the while, he longed for adventure and further education.

At the age of 16, Sandoval set out for California, or as he called it, paradise.

"I was very lucky," he said of his arrival to the West Coast. "I got here one day and started working the next day. We worked here picking fruit all around Orange County."

A few years later, his path would change yet again when he and a friend decided to enlist in the 185th Coast Artillery Regiment (antiaircraft).

"I didn't know a soldier from anything else, but it sounded good," Sandoval said.

The infantry, California National Guard regiment, prewar, was stationed near Anaheim, Calif.

Once in the service, Sandoval undertook what he labeled as his smartest move – studying. He took every opportunity to read. Because of his hard work, he was quickly promoted to Sergeant and asked to teach the daily training lessons to the other men. In only a few months, he’d advanced in rank and academics.

But adventure began in earnest on Dec. 7, 1941, the day the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor.

"I was a sergeant, not knowing too much about the military, and the war happened; and we went to Fort Lewis in Washington state for additional training and then to Hawaii ... quite an experience for me," Sandoval said.

From Hawaii, he and his company were sent to various islands in the Philippines as part of an island-hopping battle strategy.

He recalls a time when his company came across a bridge they needed to cross to unite with other troops on the other side of the island. But the bridge was occupied by Japanese forces, and would have to be captured for use by his company. Upon surveying the area, Sandoval and his men found the bridge had been strapped with two 600-pound bombs with detonating wires that led back to a Japanese camp. Given his experience with munitions, Sandoval was charged with disarming the bombs.

"I told them I didn't know the Jap's wiring code, but I guess I would have to guess and I had to work alone," he recalled.

Taking to the task, Sandoval paused for a moment, reached for his worn leather pouch and pulled out a pair of wire cutters.

"I took this pair of wire cutters. That's it," said Sandoval, resuming his story. "And I crawled on my back all of the way, on the edge of the bridge. I got to the first bomb, knowing that if it blew, that's it. Curtains," he said with a tense chuckle.

"I found a big detonator box underneath one of the beams, filled with explosives. I cut it. I found another big box and cut it, undetected. I was very fortunate. I got a dozen of my men across before we were detected.”

On March 19, 1945, Sandoval was awarded the Silver Star for gallantry in action to honor his accomplishment on that dangerous day under the bridge. An accompanying certificate details the importance of his accomplishment: "Technical Sergeant Santos Sandoval, under intense enemy fire and with utter disregard for his own safety, cut many wires under a bridge that were wired to bomb the bridge. His actions saved the bridge for the U.S. Army."

The month prior, Sandoval had a Bronze Medal for heroic achievement in the Philippines. He would also later earn the Purple Heart.

The day he secured the bridge wasn't his only brush with death. On another island in the Philippines, Sandoval and his men were attempting to capture Japanese territory up a hill when they came under intense enemy fire.

"We really got slaughtered," he recalled, remembering the image of men falling all around him and the feeling of powerlessness in not being able to help them.

He did, however, attempt to rescue one man he remembers only as "Bill," who’d been wounded by a mortar shell to the foot and was bleeding profusely.

"I finally crawled over to him and told him to get on my back. I was going over a rock and lifted a little bit too high and a bullet went through his buttocks. Of course, he was on top of me and I got blood [from] head to toe," Sandoval said.

Although his heroics earned him measures of pride and recognition, they also brought him his share of pain and suffering. To this day, he still sometimes wakes up in a sweat, reliving the nightmares of war, he says.

During one particularly bad nightmare, he grabbed his wife Adele and nearly killed her, thinking in his subconscious that he was at war. Even awake, he still has flashbacks. Whenever he remembers being soaked in blood from carrying his injured comrade, he’s overcome with nausea and disorientation.

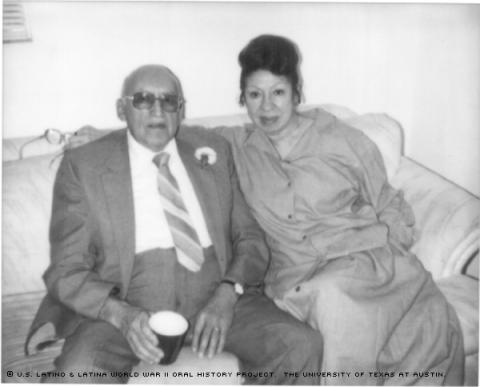

"I don't know why or how she has been able to put up with me," said Sandoval of his supportive wife. "I thought it would go away, but it has never gone away. I guess I'll die with it."

Regaining his personal independence at his July 4, 1945, honorable discharge, he secured a job with the Department of the Army, where he worked for 15 years. He then transferred to the Department of Agriculture, becoming the agency's first bilingual employee. His fluency in Spanish made his services invaluable to the agency, whose five-county region encompassed a great number of Spanish-speaking clients needing information on government services.

Back in Los Angeles, far from the jungles of the South Pacific, Sandoval and Adele enjoy the company of their four children, 17 grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren.

Mr. Sandoval was interviewed in Los Angeles, California, on March 23, 2002, by Sandra Murillo.