By Amanda Crane

Ruperto Soto Juarez, of Norwalk, Ca., has not had an easy life: he was orphaned as an adolescent; he quit school as a child, he fibbed about his age in order to join the Navy and serve his country in WWII. He has been a political activist, fighting for a fairer world. When his wife was terminally ill, he stayed by her bedside, holding her hand.

His is the story of an everyday hero.

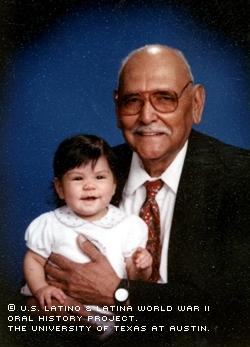

His granddaughter, Valerie Talavera-Bustillos, who interviewed Juarez last year, said in a 1-page summary: "He has shown his family that to be a good person you have to love your country, family and community."

From his childhood in El Paso, Texas, through two wars, and on into his present life in California, he recalls his past with a smile on his face. His memory is long and clear; his story, inspiring.

Ruperto Juarez began his life on March 24, 1928, in El Paso, Texas as the second son of Ruperto Juarez and Margarita Soto. His parents were hard working, loving and warm, but very strict. If Ruperto Sr. gave the children a chore to perform, he only told them once. If he had to tell them to do it again, they would be punished. Ruperto and his two brothers learned at an early age to never make their father tell them something twice.

Ruperto's family did not have much money, but according to him, neither did anyone else at that time. His father was enterprising. His regular job was to sell bread door to door. He would walk all the way through El Paso, from one end to the opposite end, selling bundles of bread from a local bakery. When he wasn't doing that, he would go out into the mountains and collect a plant he called the "lengu\a de baca" and make pan scrubbers out of it. He would go door to door and sell those, as well. Margarita, Ruperto's mother, was a housewife who prided herself on having a clean, tidy home for her family and food on the table.

"At that time all of America was dirt poor," said Juarez. "But my parents worked hard to give us clothes, and food, and keep us in good health."

They did not wear shoes to school, only to church, so that they would last longer. On his way to school one day, Ruperto found a pair of shoes, but they had a hole worn straight through the sole. They fit perfectly, so young Ruperto wore them home. When his parents asked him where he got the shoes, he explained that someone had thrown them out. His father took the pair of shoes to a shoe repair shop and got new soles put on them. Ruperto had a pair of shoes for the rest of the year and felt "just like a Yankee Doodle!"

Juarez was a rambunctious child who was always finding his way into trouble. Once, when he was about 4 or 5, Ruperto and his brother Francisco were playing at the railroad tracks. They climbed into a refrigerated boxcar filled with ice. Oblivious to the fact that there were children inside, someone slammed the door shut. Ruperto rammed his head repeatedly against the door in hopes that someone would hear him and open it. Francisco stopped Ruperto from knocking himself out and eventually someone let them out of the boxcar.

Juarez' childhood was not to last long, though. Tragedy struck him at an early age. When he was only 12 years old, Juarez's mother died of an unexplained illness.

Only one year later, when Juarez was 13, his father also passed away; he had chronic stomach problems but never saw a doctor. One night the elder Juarez went to sleep and never woke up.

The three boys had to support themselves - staying in the same house without an adult. They picked cotton and continued in school for a while. Juarez's school had almost all Mexican American children in it, but there was only one teacher. When Juarez was moving from the third to the fourth grade, he decided to quit school. This would not be the end of his education, but it was certainly an interruption.

Shortly after quitting school, Juarez's brother, Francisco, was drafted into the United States Army, so he and his younger brother, Luis went to live with relatives in Marfa, Texas, where they worked with their uncle in construction.

When Juarez was only 16, he tried to enlist in the Navy, but they told him he had to come back when he was 17, and have the consent of his parents. Since his parents were both dead, and all of his cousins and friends were signing up then, Juarez went back to the Navy office and lied. He claimed to be 18 and they did not question him because he was tall and looked older than his age. He was sworn in immediately and went for training in San Diego.

After basic training was completed, Juarez thought he would be sent overseas to serve, but they kept on putting his departure off. He heard from some other men that men who went AWOL were sent overseas immediately after they were caught. Juarez thought that this sounded like a good idea, so he left the base and headed to El Paso. But once in El Paso, he didn't have enough money to get back to San Diego. Juarez then joined the Army instead. He had almost completed his training in the Army when he finally got caught. His commanding officer asked if he had ever heard of a sailor named Ruperto Soto Juarez and he responded, "I am him."

The military police took him back to the Navy where he had a 35-day confinement period before he was sent over seas to fight in WWII.

When Juarez recalled his two years in Guam during the war, he emphasized - both in an unpublished manuscript and in a videotaped interview - the good times. Three branches of the military, the Marines, the Navy and the Army got along well "without fighting," he noted in his memoirs. The men played many practical jokes on each other: once, while a man was sleeping, Juarez nailed a man's shoes to the floor. When the man woke up and put on his shoes, he found he couldn't walk. Another time, someone put a frog in his pillow case while he slept and he woke up to the croaking.

When the United States dropped the bombs on Nagasaki and Hiroshima, and the Japanese surrendered, everyone was celebrating because the war was over. Juarez and his friends filled tubs with beer, cooked some homemade Mexican food, and sang and played the guitar. When a couple of Anglo sailors passed by their party, Juarez heard them say, "Those Mexicans can really party."

Once Juarez got back home to El Paso, he married his girlfriend, Guadalupe Martinez, in Las Cruces, New Mexico. But finding depressed wages in El Paso, Juarez left his bride and went to work in Indiana where the wages were higher. He later came back to El Paso and enrolled in El Paso Technical Institute, a high school, and completed ninth and tenth grades. Juarez enlisted in the Naval Reserves and before long was called back into duty for the Korean War.

Juarez served on the USS Wiseman during his duty in Korea. The sailors on the ship were all in the reserves and, like him, had all fought before. They were not as friendly as the men he had served with in WWII. He said that it was not a racial conflict, whites against Mexicans, but instead, "nobody liked anybody there." Many fights broke out between the sailors. One afternoon, Juarez was at a nightclub in Korea, having a good time with his friends, when a heavyset man from his ship picked him up from the back of his collar and told him, "Shut up you damn Mexican," and began beating him up. Startled and confused, it took a little while for Juarez to fight back, but eventually he did. The man's friend also jumped in, but Juarez took them both on and won the fight. Finally the Shore Patrol came and broke up the fight, but once everyone heard that the two men had attacked Juarez from behind, and that he had still defeated them, they were known as the cowards of the ship.

Juarez was released from active duty in 1952, and he and his family moved to California. He had several jobs, but eventually settled down to work for the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company, where he continued to work for 24 years. He also took advantage of the G.I. Bill and went back to school at Compton Junior College, so that he could receive training and get a better job at Goodyear. After working there for 11 years, the management at Goodyear told Juarez that even if he were to get his associates degree, they would not put him to work in the machine shop.

In the 1960s, in Compton, Juarez joined the Mexican-American Political Association of California (MAPA), where he and other concerned citizens worked to get Mexican-American people elected to political offices. He worked with MAPA for 30 years. Juarez himself ran for city council - unsuccessfully -- in 1994.

Although Juarez feels that he has had many wonderful experiences and opportunities, he still feels that Mexicans are sometimes treated unfairly.

"They always said that if you get the proper training and get a vocation, you can get the job you want, but it's not true," said Juarez. "You still have to swim the widest ocean and climb the highest mountain."

Juarez documented his life story in a book he authored entitled Memoirs of Ruperto Soto Juarez, which he wants to get published soon. He also had some words of advice for young Mexican-Americans.

"Mexican-Americans need to know that this is their country," he said. "As long as you have faith in God, you can accomplish anything, whether you're Mexican or whatever race you are, because if you don't have that, you don't got nothing."

(Mr. Juarez was interviewed by his granddaughter, Valerie Talavera-Bustillos, at his home in Norwalk, Ca.)