By Beth Nottingham

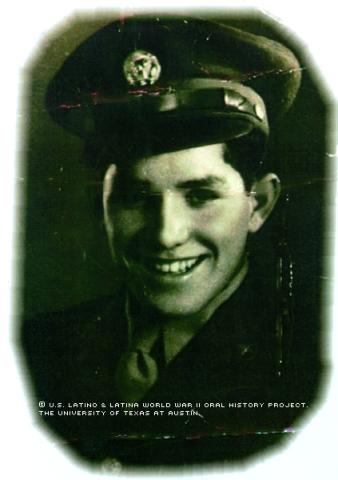

Roberto Gonzalez had a Sunday tradition of listening to news about World War II on a big old radio in the living room with his dad, Catarino Gonzalez. Little did he know that his love of radio would be his ticket to making his father proud by serving his country.

Gonzalez was always a hard worker. Before the war, he was a member of the National Honors Society, balanced his time between school, working at his father's grocery store and playing basketball and baseball. After he was drafted in 1943, when he completed high school in Harlingen, Texas, he immediately chose to serve as a radio and Morse code operator for the Air Force.

"I was given an IQ test and an aptitude test for languages and math," he said. "I scored pretty high."

Soon after testing, Gonzalez found himself at Shepherd Air Force Base in Wichita Falls, Texas, where he was forced to balance his schedule by doing drills in the cow pasture every morning at the crack of dawn and then studying all day. All of the hard work paid off. He promptly rose to the top of his class and was officially named a radio operator and shipped off to Sioux Falls, South Dakota, for radio school.

After completing his studies in Sioux Falls in 1943, Gonzalez was selected to go to advanced radio school at Scott Field Air Force Base in Illinois.

He received rigorous advanced training in air to ground radio communication and was assigned to bomber-unit training in Lincoln, Neb. After completing the final training in preparation for going overseas, he was assigned to a B-29 Bombardment Wing, which later operated out of Guam. Upon arrival at the war zone, he was assigned to assist construction crews working to build the runaways that later launched the bombing attacks in Japan.

The backbreaking work wore out everyone in the crew, so sometimes entertainment was flown in to take their minds off of the daily grind. Even though Gonzalez appreciated the performers, he regrets never seeing heavyweights like Bob Hope.

"Bob Hope came to every camp in the Pacific except for mine," he said.

Other comforts came during mail call: his father's letters, which were in Spanish, and sweet treats from his mother.

Gonzalez served in different parts of Micronesia, specifically Marianas, Tinian and Saipan. Eventually, he ended up in Guam, were he stayed for the majority of the war. The United States established a colonial regime in 1899, which was disrupted when the Japanese had occupation of the island during WWII. Gonzalez stayed in the radio room transmitting and deciphering code, as well as updating soldiers with information and weather.

Soldiers were required every morning to wake up and do drills or some other sort of strenuous activity. Even though the job was stressful, Gonzalez and his men would find ways to combine doing hard tasks with doing something fun.

"Our favorite athletic pastime was softball," he said.

Even though there were only about four or five Latinos in his group, Gonzalez said, he enjoyed the mostly colorblind attitude in the Air Force -- a far cry from high school in Harlingen, where he couldn’t swim in the same pool or join the same clubs as whites.

No interracial dating was allowed in Harlingen, but, Gonzalez noted, "there were lasting friendships."

He didn’t experience a lot of discrimination in the Air Force, "because we were all fighting for the same cause," he said.

However, the military wasn’t a utopia.

"Every Hispanic was called 'chico,'" he said. "And I resented that everyone mispronounced my last name."

In 1946, Gonzalez ended is three-year stint in the military with a final rank of Staff Sergeant and went back to his hometown.

After coming home to Harlingen, Gonzalez took advantage of the GI Bill and came to school at the University of Texas at Austin in June of 1946 to pursue a career in accounting. He received his BBA in accounting in 1952, and went on to complete his master's degree in Public Administration at the University of North Texas in Denton in 1974.

It was at a Presbyterian Church camp in Kerrville, Texas, where he met and fell in love with his wife, Eloisa Mojica. The two married in 1949 and settled down in Austin and had five children: Norma, Catherine, Ruth, Lisa and Robert. Gonzalez worked as a federal auditor for 12 years in the U.S. Department of Health Education and Welfare, and finished his 21 years of Federal Service as Deputy Director of the Office for Civil Rights in the Department of Education, based out of Dallas, TX. He’s currently continuing his education by taking classes in French and History.

Mr. Gonzalez was interviewed in Richardson, Texas, on June 17, 2000, by Kevin and Sharon Bales.