By Jordan Haeger

Richard Manriquez served one tour in Vietnam, and he came back a changed man. He saw dead Americans, 15-year-old Vietnamese prostitutes and young suicide bombers.

It took him a long time to begin to heal.

"War has torn my soul," he said.

Manriquez, an auto mechanic turned body collector, witnessed things in Vietnam that haunted him the rest of his life.

The bitterness and sadness Manriquez felt were clear in writings he recorded at his therapist's request. He provided copy of his written story to Voces.

"My name is Richard Manriquez, I am 63 years old and this is my story," he wrote.

"To begin with, I had no plans to go into the service but I guess Uncle Sam took care of that."

Manriquez was working in the mailroom at the Firestone Tire and Rubber Co. He was on his way to managing his own store in Houston when he was drafted. He said he felt angry at the U.S. government for sending him to fight in a war he knew little about, and he didn't care about spreading democracy.

"Sometimes our values are not everybody else's values," he said.

Manriquez could have avoided the war zone, had he followed his mother's advice. As he was getting ready to board a plane to Vietnam in the fall of 1968, his mother insisted on being alone with him on the walk across the tarmac. Once they were alone, she pulled $40,000 in cash and a plane ticket to Mexico and implored her son to flee.

"Son, this is not your war," she told him. But Manriquez was not a draft dodger.

He boarded the plane and took the 19-hour flight to Saigon, where he and about 75 others were then bused to Long Binh, an Air Force base about 60 miles outside of Saigon.

Manriquez was entering a new world. Growing up in Houston, he attended Catholic schools - first St. Joseph's School and then Mount Carmel High School. When he entered the military, he was assigned to the 326th Medical Battalion of the 101st Airborne Division. Since he had worked in body shops, Manriquez had the responsibility of fixing military vehicles at Bien Hoa in the southern part of Vietnam.

Only three months after the Tet Offensive, casualties were high at Bien Hoa; Manriquez's job shifted from repairing vehicles to collecting wounded soldiers and the bodies of the dead.

"A human body is kind of like a watermelon. When it gets hit by a round it almost explodes," he said.

Manriquez said he saw many of these dismembered bodies and smelled the stench of the dead as he tried to match arms and legs to the soldiers to which they once belonged.

"It's tough to pick up a body, if someone gets hit by a machine gun; his limbs are spread over a 15-foot area. It's hard to match the body parts," he said.

After making the sign of the cross, Manriquez would throw the body in a bag and move on to the next one.

Though Manriquez had no confirmed kills, he recalled a time when an armed Vietnamese man charged at him and five other soldiers, taking each of their bullets before he fell. Manriquez said he believed the man was under the influence of some drug.

Drug use was rampant amongst U.S. troops as well. Manriquez said many soldiers used alcohol, marijuana, or pills. He often drank surgical alcohol mixed with grapefruit juice to combat the boredom and loneliness of being at war.

During the last six months of his tour, Manriquez and his unit moved north, where the sound of guns from the artillery unit next door could be heard constantly. He said it was impossible to sleep; even at the time of his interview he said he still had sleeping problems.

While in Vietnam, Manriquez broke his ankle and was awarded a Purple Heart. But, at the hospital, he was disturbed to see men with more serious injuries and later refused to accept his medal.

"The guy on my left had his arm blown off and the guy on my right had his legs blown off and I only had a broken leg," he said. "I was furious because they came to me and gave me the medal first."

He was also awarded a Bronze Star and an Army Commendation Medal among others for his service.

Manriquez was discharged in May of 1969.

Ninety days after returning from Vietnam he married his wife, Olivia Rodriguez. Not long after their wedding, Manriquez said he woke up in the middle of the night and pushed his wife out of bed and yelled at her to duck.

Over the next several years, the couple had two children, Renee and Tim. He earned an associate's degree in sociology using the GI Bill, and eventually opened his own body shop in Houston in 1980.

Manriquez said it was the business of life that kept his post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms at bay. As he got older, he did begin to relive the past. He sometimes cried uncontrollably and was unable to sleep or keep his emotions hidden. He said he feared he did not do everything he could to help his fellow soldiers.

In 2011, Manriquez said he was accused of pointing a pistol at his wife. That resulted in their separation. He said he did not remember the incident, but his actions estranged him from family.

"Anybody that says war does not affect you is a liar," he said. "We're not born killers; we're made to be killers."

It was his fellow veterans that convinced Manriquez to seek help from the Veterans Administration. He was diagnosed with PTSD by a VA psychiatrist and prescribed antidepressants, which he did not take.

He was the junior vice commander for VFW Post 9187 as well as a member of the American G.I. Forum and an advocate for homeless veterans.

Manriquez struggled daily with the emotional scars the war left him, and how they affected his family. Though he felt bitter at having been drafted, he did not regret his experience in Vietnam. He considered himself a patriot and was proud to have served his country.

Between tearful pauses and apologies for the tears, Manriquez said, "This is the best country in the world."

"It has its faults, but its faults can be overcome," he said.

Mr. Manriquez was interviewed by Jordan Haeger in Houston on April 9, 2011.

Disclaimer: The Voces Oral History Project attempts to secure review of all written stories from interview subjects or family members. However, we were unable to secure that review for this story. We will accept corrections from the interview subject or designated family members. Contact voces@utexas.edu.

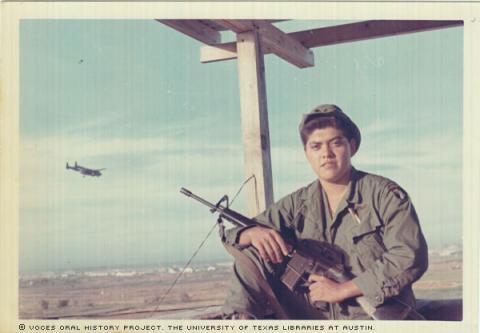

![Vietnam Vet, Richard Manriquez, was interviewed in Houston, Texas, on April 9, 2011. [Voces Oral History Project/ Michelle J Lojewski]](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/IMG-896-02-600.jpg?itok=-RO_Zvff)

![Vietnam Vet, Richard Manriquez, was interviewed in Houston, Texas, on April 9, 2011. [Voces Oral History Project/ Michelle J Lojewski]](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/IMG-896-03-600.jpg?itok=OSbWHzt8)