By Joshua Avelar

For Richard Geissler Jr., a U.S. Army veteran who became a conscientious objector during the Vietnam War, passion for community activism shaped his life despite the many different communities he served and the overbearing obstacles he faced.

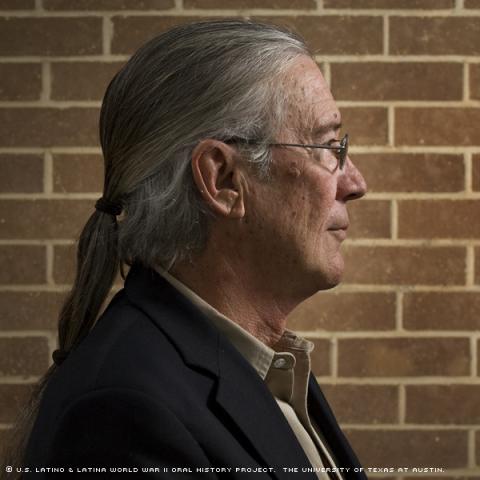

Geissler, 64, with tired eyes, silver hair tied back into a pony tail and South Texas vernacular, spoke about his life of community activism from parks in Venezuela to the streets of New York City to the bridges of South Texas border towns. Having spent much of his life working and living among Latinos, Geissler said he considered himself a Latino by experience.

Born in White Plains, N.Y., Geissler moved with his father Richard Geissler Sr. to Venezuela when he was just 6 months old. The elder Geissler, a World War II veteran who served under Gen. George S. Patton in North Africa, was an engineer and helped develop new high-rises in the booming Venezuelan capital of Caracas.

Geissler grew up throughout Venezuela, wherever his father's job would lead the family. His younger brother, William, was born in Venezuela. It was there that Geissler, though the only “gringo” in his schools, learned the importance of community from the people he grew up around.

"My sense of fairness I got in Venezuela," Geissler said. "You treated people decently, no matter rico or pobre."

Venezuelan military dictator Marcos Perez Jimenez rose to power during Geissler's youth. Geissler recalled the fear that gripped Venezuelan communities during Perez Jimenez's reign . Geissler said that Perez Jimenez had a secret police force that came after anybody that spoke out against the dictator or his policies.

“I saw people in park demonstrations, and then these [police officers] would come out of nowhere,” Geissler said. “I know exactly how these Iranians feel.”

Geissler's father died when Geissler was 15 years old. Having never known his biological mother, Geissler moved in with relatives in Scarsdale, N.Y., a suburb of New York City. The move to Scarsdale was just the second time in his life that Geissler had ever been to the U.S.

“The shock to me was New York City,” Geissler said, “after living in small towns in the boonies.”

Because of his upbringing, Geissler befriended many of his Latino classmates. After high school, Geissler began organizing rent strikes in the Southeast Bronx. To avoid being drafted into the military during the Vietnam War, Geissler joined a domestic version of the Peace Corps called Volunteers in Service to America. Geissler said VISTA members were sent wherever their skills were needed. Because of his fluency in Spanish, Geissler was sent to the South Texas border town of Laredo.

“I got a map,” Geissler said. “Where the hell is Laredo, Texas?”

In Laredo, Geissler saw a community that needed organization against great oppression. In 1966, Geissler noticed that Laredo still had poll taxes and reading tests at their local polling station to keep the poor from voting. He helped organize a strike by Laredo waitresses who were demanding a fair, minimum wage from their employers.

Geissler helped stage blockades at the border-crossing bridge in Rio Grande City, Texas, in order to prevent Mexican laborers from crossing into Texas and breaking strikes. He said his life was threatened by a member of the Texas Rangers – the Texas state law enforcement agency – even though the blockade was out of the Rangers’ jurisdiction on the Mexican side of the bridge.

“He pulled out his gun and said, 'Look, I've killed 20-some-odd people and I don't count the niggers and the Mexicans,' ” Geissler said. “The Texas Rangers were the strike-breakers. They were scumbags, for the record.”

Though the demands of the restaurant strike were eventually met, Geissler said he was kicked out of VISTA for organizing the strike, and he was drafted into the Army in 1967.

Geissler went to basic training in Fort Polk, La., where he filed to be a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War. He was Catholic, and he pointed to Vatican doctrine as grounds for his objection.

“Your conscience is God speaking to you,” Geissler said. “If I was in World War II at the Battle of the Bulge I'd be killing Germans, but [Vietnam] was an unjust war.”

During his time in basic training, Geissler's first wife, Donna McKelroy, who he met and married in Laredo, had her third miscarriage. Geissler was denied a leave to visit his wife at this troubling time. So Geissler went AWOL. He returned to Fort Polk just before the 30-day deadline when he would have been declared a deserter.

Geissler was sentenced to 105 days in a military prison as punishment for going AWOL. He ended up in Fort Sill, Okla. where his Military Occupation Specialty was changed to be a cook. He reached the rank of E5 and was honorably discharged.

McKelroy left Geissler, but he gained custody of the only son they had together. He married Jacqueline Frank of Laredo in 1972 and had a total of four sons and two daughters. Geissler continued his activism in Laredo throughout his life. Most notably he participated in a successful fight for single-member districts for Laredo school board and city council elections.

At the time of his interview, Geissler was a member of the Laredo Veterans Coalition, a collective to support war veterans that Geissler believed were and still are neglected by the government.

“I believed in national service and I still do,” Geissler said. “I was trying to do that with VISTA. I think the problem with our kids today is that they have no sense of nationalism.”

Mr. Geissler was interviewed in Laredo, Texas, on March 6, 2010, by Frank Trejo.