By Courtney Stoutmire

Richard Dominguez counts his "blessings" every day when he remembers his time in World War II. The best part: It was short and sweet.

Dominguez was drafted in June of 1943, but he wasn’t sent into combat until more than a year later, only a month before the United States dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945.

"I was fortunate that I spent time in various branches of the Army and didn't go overseas until just before they dropped the atomic bomb on the Japanese homeland," Dominguez said. "Quite a few fellows I knew and grew up with were killed in the war, including my older brother."

Three days later, a second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, effectively ending the war.

Dominguez says one of his most memorable experiences during WWII was his selection to the Honor Guard for Gen. Douglas MacArthur during the occupation of Japan.

"They picked the tallest, ugliest, most vicious-looking guys because they wanted to impress the Japanese, I guess," he said.

As part of the honor guard, Dominguez had the privilege of escorting MacArthur to the USS Missouri battleship to sign the peace treaty on Sept. 9, 1945.

Dominguez was discharged in March of 1946 as one of a handful of Chicano staff sergeants. His two elder brothers were enlisted men in the 4th Division of the Marines. Part of Dominguez's decision to leave the military -- even after being offered a promotion and a bonus -- stemmed from the death of his brother, Eugene, who was killed by a sniper in Saipan toward the end of the war.

"I wish I had stayed, because I hadn't been overseas for that long," he said. "I was just kind of foolish, I guess, and I wanted to go home."

Dominguez grew up in tight-knit Boyle Heights, a multicultural neighborhood in East Los Angeles. The families, largely immigrants, were close. Most families attended the Catholic neighborhood church, La Purisima, every Sunday.

"Our social and educational lives centered around the church," Dominguez said. "The families knew who you were. You knew they knew you were a Dominguez."

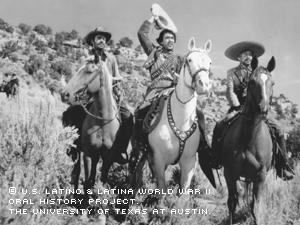

His father, Jose, was a Latino pioneer in Hollywood, starting as an extra in the silent films of the 1920s and as a bit player later in the "talkies." Dominguez’s mother, Frances Almaraz Dominguez, also worked in Hollywood films, but concentrated her efforts on raising 10 boys. When growing up, Dominguez and his brothers also worked as extras in films.

The couple labored tirelessly to send nine of their sons to parochial schools so they could receive a better education, Dominguez says.

"It was quite a feat for nine brothers to graduate. It was quite a feat to be able to afford it," he said.

Though he attended Cathedral, a parochial high school, he transferred to Roosevelt High School in Los Angeles to participate in ROTC.

Dominguez was a senior in high school when Pearl Harbor was bombed.

"Being 17 years old, I didn't know how it would affect me, but I thought about some Japanese friends from school and wondered how it would affect them," said Dominguez in writing after his interview. "We soon found out."

Although his father was a volunteer air-raid warden for his block and his mother had joined a group of Hispanic mothers with sons in the service, Dominguez’s parents still worried for their two children, Joe and Eugene, who’d volunteered for the Marines in 1942.

"Being a parent now I can only imagine what they must have gone through in those years," Dominguez wrote to the Project. "They placed their trust in the Lord, prayed daily for us and did what they could for the war effort."

Dominguez would soon join his brothers on the warfront; he was drafted in June of 1943.

"I wanted to be in the Air Force," he said. "I wanted to be a pilot."

He was accepted by the U. S. Army Air Corps and was sent to Tempe, Ariz., for training at Arizona State Teachers College. Due to a need for "more men in the regular Armed Forces," Dominguez said he and the rest of his class were sent to Texas’ Fort Hood after only three months. He says he almost joined an anti-tank battalion but decided against it.

"I wanted to fly, and I figured the next best thing was to be a paratrooper," he said. "They were prestigious and wore special boots, and they really pumped you up as you went through training."

After getting his wings at Fort Benning in Georgia, Dominguez was sent to Maryland to prepare to go overseas to Europe.

"So we were there, ready to go, getting our shots and clothing," he said.

The German army was getting destroyed during the first half of 1945, however, rendering Dominguez’s transfer to Europe unnecessary. He trained for six more months at Camp Mackall in North Carolina, before shipping out to the famous 11th Airborne Division in the Philippines in June of 1945.

Dominguez had been in the Philippines for only a month when Hiroshima and Nagasaki were bombed. He recalls wishing he’d been more involved in the war effort, but, looking back, realizes he was fortunate because "war is a terrible thing."

After returning to Los Angeles, Dominguez obtained his Screen Actors Guild card and dabbled in movies. He used the GI Bill to resume his education, attending East Los Angeles Community College for two years and California State for a year.

In June of 1949, Dominguez married Norma Rafaela Romero.

Norma did her part during the war to boost morale, Dominguez wrote to the Project. As a child, she learned Mexican and Spanish songs and dances, performing them with one of her brothers into their early teens. During the war, her mother, Rosa G. Romero, formed a group for mothers who had sons in the service. The mothers would serve as hostesses for the USO.

Norma continued to sing throughout her high school days. She regularly performed at War Bond Rallies and traveled to nearby bases and camps to entertain the troops, Dominguez wrote.

"The Lord has blessed me by giving me such a wonderful wife and mother to my children," Dominguez wrote. "We were married 51 years before she passed away."

Dominguez began a career as an investigator and community relations detective for the Los Angeles Police Department in November of 1948; he was the only Latino recruit in a class of 75. To earn extra money, he joined the National Guard in 1950 and was called away to the Korean War for two years. He served in both Japan and Korea.

Dominguez served as a first sergeant in the 40th Infantry Division until September of 1952, when his mother fell ill and he returned home to care for her. He wanted to rejoin the National Guard after Frances recovered, but Norma put her foot down.

"I would have stayed, but my wife didn't want me to," Dominguez said. "I wanted to make a career out of the National Guard. We had a family by then, so I didn't enlist again."

Through the years, Dominguez regretted not staying in the National Guard because his friends who did advanced in rank and retired with pensions.

Instead, Dominguez went to a junior college to become a schoolteacher. But in his second semester, he was recruited by the Los Angeles Police Department. There, he witnessed discrimination for the first time. He says Chicanos were more likely to be mistreated when they were arrested.

"I was a rookie. I had to keep quiet," he said. "I didn't like it, but I didn't think there was anything I could do."

Dominguez persevered, even using his ethnicity as a tool.

"Being bilingual helped a lot. It was very helpful in interviewing victims, witnesses and suspects," he said.

While he was a police sergeant working community relations, his two younger brothers were also promoted to Sergeant. At the time, they were the only three-brother sergeant group in the LAPD.

Dominguez served the community for 25 years before retiring. He raised eight children with his wife and now helps raise his 18 grandchildren.

After retirement from the police department, Dominguez was hired by the city of Los Angeles as a "Hearing Officer," in a new program initiated by the city attorney. The program was created to relieve congestion in the courts; minor criminal offenses were resolved in an office setting, still allowing for all parties to be heard. The program was successful, says Dominguez, and is still in action today.

Dominguez retired for the second time in 1985, after serving in this position for 10 years.

He says he has led a full, happy life, and still recalls his wartime experiences fondly.

"It was a learning experience. I got to know people from other countries and other cultures," he said. "I'd recommend the military to anyone for an education, an adventure and a good living. Thank the Lord, it's been a good life."

Mr. Dominguez was interviewed in Whittier, California, on March 26, 2003, by Steven Rosales.