By Shelby Tracy

Raymond J. Flores has always been a fighter.

He volunteered for the Army in the midst of World War II, but a defective leg kept him from fighting overseas.

His lifelong battle for freedom would be done on the home front.

Born in the small mining town of Miami in southwest Arizona, Flores was one of 17 brothers and sisters. His mother, Rosa Holguin Johnson, was from Tularosa, N.M., and his father, Aurelio Maldonado Flores, immigrated in 1905 from Guanajuato, Mexico.

Flores says he became aware as a young boy in Miami of the racial inequalities he’d spend his life fighting to overcome.

Because of a diverse and extensive family heritage, he was exposed to several languages in his home, including Spanish, English, German, Apache and French. His mother had relatives in England, and his father had forebears in Belgium. His contact with Native Americans in his hometown gave him a reason to learn Apache. Because of this exposure, Flores says he was fascinated with languages and wanted to teach others.

As a child, Flores says he often found himself as the outspoken fighter, the teacher and the role model for the other Latino children in his community.

When he entered elementary school, Flores became the first child of Mexican heritage to join the "American" class in a segregated school. He recalls his mother as a "fighter for the rights of people," and says she was responsible for enrolling him, and later his brothers and sisters, in the "American" classes.

Flores remembers the growing racial inequality in his town while he was in high school. He led the first ethnic student walkout at his school in 1939, because the yearbook pictures segregated students by "national origin even though we were all U.S. citizens by birth," Flores explained.

"It was a period of racism to the extreme when I was growing up," he said.

But this wasn’t something he was willing to accept.

"If you get accustomed to [racism], it doesn't hurt as much," he said. "But we didn't want to be accustomed to that. It was just not our way."

After the war, he led several economic boycotts among Latino youths in Miami and surrounding towns to fight against ethnic discrimination.

Although he had a brother who was three years older, Flores' father appointed him to take the role as the oldest son and partner in his company, the A.M. Flores & Sons Construction Company.

Flores says even though his brother had been conditioned to be a "humbled Mexican," this was something he couldn’t tolerate.

"Para mi, no habia 'sombrero en mano (For me, there wasn’t a sombrero in hand),'" he wrote in a letter to the Project after his interview.

Flores began working for his father when he was in the eighth grade.

During his high school years, he attended school one day a week to pick up and turn in assignments and take tests. He worked the rest of the week for his father. His experience in construction would give him the background he needed to be a draftsman in the Army.

Flores had always enjoyed teaching others. For example, as a boy, he remembers instructing the young Apache children in his village on how to write their names in English. Grateful for his assistance, the Apaches made him an "honorary Apache warrior."

Flores went to college in 1941 to escape the mining life expected of Hispanic boys in Miami, and to pursue his dream of becoming a teacher. He says he was the first person from Glover Barrio in Miami to go to college. He attended Arizona State Teachers College, now Arizona State University.

Flores says his peers initially were critical of one of their own attending college and embracing the "gringo" way of life. But his success inspired many other Latinos from Miami to break away from the usual Mexican life as a laborer in the mines, he says.

"It was an institutionalized form of abuse to keep people in their so-called place," he said.

His plans to be a teacher were put on hold when he enlisted in the Army Air Corps in 1942. He enlisted because he didn't want to go into the infantry or cavalry like most Hispanic draftees were forced to do, he says, because he had a bad leg and a strong dislike for horses.

Even in the military, Flores says he encountered the "same old racism" he’d spent his youth fighting to overcome.

"I hate to discredit different parts of the military," he said. "But racism was rampant."

Flores says he out-shot everyone in his unit during basic training, yet because of his heritage, he was the only soldier not promoted. He was the only Latino in his basic training group.

Despite signing 10 waivers, he wasn’t allowed to go to Germany because of his defective leg. He’d wanted to go overseas to develop his German language skills, but "The Army doesn't think that way," he said.

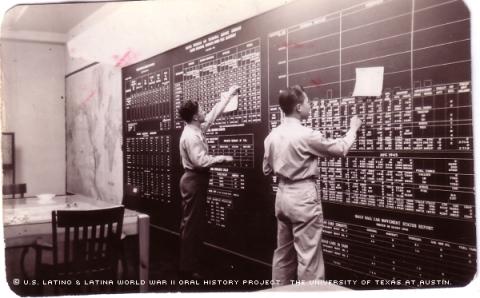

Because of his extensive knowledge and experience with construction, Flores was made a draftsman and helped design buildings and other facilities for four air bases in California. His first assignment was at the San Bernardino Technical Service Command (Engineering Office). Although unable to get a promotion because he had no unit and hadn’t spent any time in a combat zone, Flores was provided an Army vehicle and became the only private with a means of transportation. He also was given a book of passes that allowed him to come and go anywhere he pleased when not on duty.

Eventually, Flores transferred to Oakland and worked for counterintelligence on the side. He was chosen to investigate suspected sabotage at the San Bernardino base after the mysterious crash of 13 aircraft. His superiors thought he’d be the perfect man for the job of uncovering a saboteur because, in his long struggle to be treated equally, he wasn’t partial to anyone.

He was then assigned to the Pacific Overseas Air Technical Service Command, and later was in the U.S. Naval Security Command.

Even in the military, Flores used his ability to teach by helping Hispanic soldiers from Texas learn "Army English." For two hours every morning, he taught the grateful soldiers the words they needed to understand in order to follow basic commands and avoid punishment.

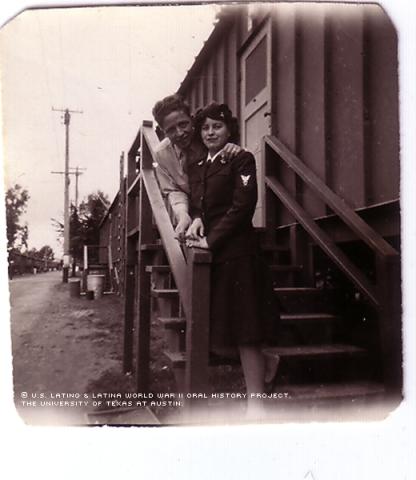

After the war, Flores returned to Arizona to complete college at the University of Arizona in Tempe and begin his career as a teacher. But he returned to military intelligence in order to help support a wife and family after he found the woman he’d marry.

His future wife, Leota May Resler, was a tuberculosis patient in the same hospital where one of his sisters was being treated for the disease. Leota Resler, then 17, had had the illness for four years and wasn’t expected to live. Despite this, and an almost 12-year age difference, she and Flores married in 1951. They had six children and spent 47 years together until her death in 1998 from pneumonia.

In his career as a teacher, Flores continued to fight for equality. He began a program where high school students of different ethnic and religious backgrounds came together once a week to discuss their thoughts about each other and themselves. Called ANYTOWN, Ariz., the program saw much success and was adopted for use in several other states. Flores received an award from state Attorney General Robert Corbin for his work in human rights.

Of the racial situation in Arizona today, Flores said, "There has been some improvement, but not in the volume that improving the condition deserves."

His time serving his country in the military is only one part of his lifetime struggle to fight the "ogre of race relations" in America, Flores says.

Mr. Flores was interviewed in Phoenix, Arizona, on January 4, 2003, by Violeta Dominguez.