By Gabriel A. Manzano, Jr.

Pete Prado recognizes the brutality and inhumanity of war. But he also knows that because of his experiences during World War II and because of the GI benefits that resulted, his life and the lives of his three daughters and wife are far more comfortable.

"I hope that younger generations realize that war is terrible," Prado said. "We don't want it to happen again. When I was in the Philippines, I saw people picking up what you'd throw away as trash. Some people would pick it up to eat. That's how bad war is."

Prado's war experiences followed a childhood of work and little opportunity for education.

As a youngster, he helped his father and older brother, Edward, peddle everything from sweet potatoes to watermelons on the streets of San Antonio. During the summer months, he traveled up north to Dallas and Red Oak, Texas, like many other poor families, to pick cotton.

Prado's parents died within one year of each other, leaving him, at the age of 14, in the care of his oldest sister, Bessie. The youngest of four, Prado was then forced to quit the 7th grade and go to work selling produce and newspapers.

He recalled the day he sold more newspapers than ever, as he yelled out the headlines for the day: "Extra! Extra! Lindbergh baby kidnapped!"

These were simple times when the San Antonio Light cost a nickel.

"If you made 75 cents in profits for the day, you were doing pretty good," he said.

Prado grew up at a time when segregation and racism were continually evident in the South Texas educational system. At San Antonio's David Crockett Elementary, which was 97 percent Anglo, he remembered the day when he and a fellow Mexican American student were transferred to another room. The Anglos in that class quickly complained about not wanting Mexicans in their homeroom.

"When you're young, it's a funny feeling, of not being wanted," he said. "I felt shame."

For fun, he enjoyed playing soccer or sandlot baseball, and hanging around the street corner light with his neighborhood buddies.

"In those days, we used to hang out and just talk to each other and play games, because hardly anybody had any jobs," he said.

Prado recalled the day he and three other friends hopped a train to California in search of jobs.

"I left with 50 cents in my pocket," he said. "It took us three days and four nights just to get there, and as soon as we got there, we heard that police were looking for vagrants. So we came back after spending just one night there."

At the age of 19, Prado moved to Houston for a year with his sister, Bessie, and racked cue balls for men who waged on 9-ball. He then came back to San Antonio and found himself unemployed. Prado vividly recalled the day he was visiting a friend at his corn tortilla shop and had just found out about the attack on Pearl Harbor.

"They're going to get you," his friend told Prado. To which Prado replied, "I'm ready. And I'll go wherever they send me."

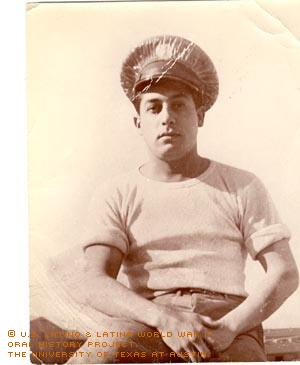

Prado was drafted into the Army Air Forces and immediately taken to basic training at Kearns Field, Utah.

While in the Army Air Forces, serving in the 860th Engineer Aviation Battalion, he and his fellow servicemen embarked on a 19-day voyage to Australia, arriving on Nov. 13, 1943, where he recalled men turning as "white as a sheet of paper" due to seasickness. At another point, he witnessed a kamikaze pilot getting shot down by a P-38, a small fighter plane specially designed for dogfights, narrowly missing him and others on the deck of the ship.

"Our front gunner was shooting at him, and right before the airplane was going to hit us, it veered to his left, and I could see that he [the pilot] was dead."

Not long afterward, a young Anglo lieutenant named Newman, whom he chauffeured and grew to admire and respect, died on Owi Island, located in the Dutch East Indies, now Indonesia.

"Every island that we went to we had to dig a well for water," he said. "And after they got so, so deep, two men went in there and they didn't come up. And this lieutenant went down to find out what was happening. Downstairs there were some kind of gases, and they choked."

All three men apparently succumbed to deadly natural gases.

Prado experienced both equal, respectful treatment and prejudice from fellow servicemen. He found himself defending his race on several occasions.

"This Anglo guy (from Houston) was arguing with a guy from San Antonio. He said, 'You got nothing but blacks over there.'"

The other guy responded, “But what do you have in San Antonio? Mexicans. All you have are Mexicans over there,” Prado recalled. “And he was stronger, bigger than I am. But I figured I'll fight this son-of-a-bitch, I'll bite him! Cause I couldn't stand for that, for them to speak about my people."

So Prado replied: "Dietz, come here. You know, I'm a Mexican-American. But if you think you're a better man than I am, let's you and I go down there and one of us has to come back!” The young man from Houston quickly apologized.

Prado and his fellow soldiers made adjustments. He and others quickly learned how to concoct their own brew out of fermented apricots, potatoes and sugar. The "jungle juice" was their stress relief in the small remote coastal areas of Australia and the Philippines.

"It would get you feeling pretty good," Prado said.

While on Biak Island, also located in the East Dutch Indies, natives showed him how to make "tooba," made from the resin of indigenous palm trees.

"It smelled like rotten feet, and you had to pinch your nose in order to drink it," he recalled.

He also remembered the large field rats the natives would burn to a crisp, "until it looked like a chicharron (a fried pork rind)."

"They would offer it to us," he said. "But I couldn't stand it, no."

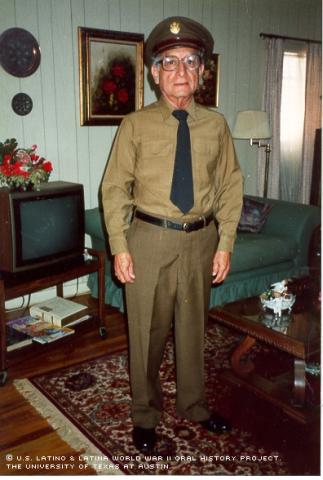

For his service, Prado earned the Good Conduct Medal, Asian-Pacific Campaign Medal with three bronze campaign stars, World War II Victory Medal and Philippines Liberation Medal.

After being discharged in 1946, he used the GI Bill of Rights to go to electrical wiring school. His skills got him a job at Kelly Air Force Base in San Antonio, and he retired in 1978.

In the course of his career at Kelly, he realized how his lack of education held him back from being promoted over others in his work.

"I remember I went one time for an interview for a promotion to a supervisor," he said. "I was sure I had better qualifications than the Anglo, who was also interviewed, but the other Anglo got the job. But there was not much I could do [about] it, because I lacked the education."

The lives of Mexican Americans have improved dramatically since the war; education is possible for anybody who wants it, he said. His own daughters are professionals: one is a registered nurse, another teaches nursing and the third is in social work. Prado is proud of the fact that two of them have also fought for their country. The oldest, Cecelia Stanford, recently retired as a lieutenant colonel in the Army, where she participated in the Panama Invasion. The youngest, Bessie, was a major in the Air Force, where she was involved in the Persian Gulf War.

Prado's pride isn’t limited to his own family. He likes to see Mexican Americans go far in all areas, including politics and sports. Congressman Henry B. Gonzalez and pro golfer Lee Trevino are among those for whom he has much respect.

"If I see a Mexican American make good, I feel somehow or another, he fills something for his own people," he said.

Mr. Prado was interviewed in San Antonio, Texas, on September 25, 1999, by Maggie Rivas-Rodriguez