By Eric Latcham

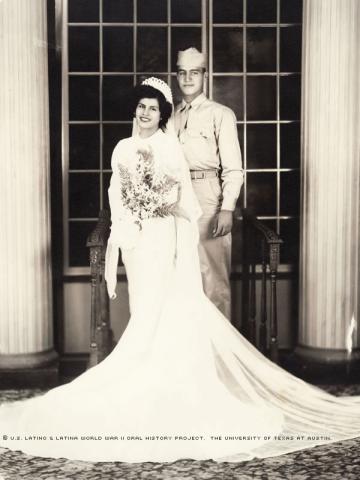

When her new husband shipped off for the Philippines, Olga Delgado Flores was pregnant back home in El Paso, Texas.

Only 15 years old when she married 18-year-old Ramón Flores, she had dreams of a better life for her family and had been encouraged by a local principal to go to college. Flores soon learned, however, that traditional-household caregivers had limitations placed upon them.

“When I got married I thought I would keep going to school, but my mother-in-law said, ‘No, if you wanted to get married, you cannot go to school. You’re going to have children and tend to your housework,’” Flores recalled.

Her husband echoed those same sentiments: Her baby and family needed her to take care of them. This was the beginning of a reoccurring theme of selflessness throughout Flores’ life, where her family was put above personal goals and dreams.

“We used to be very obedient in those days,” she said with a smile.

Flores never went back to school, but that didn’t stop her from studying. She learned the importance of education from her mother, María Urquizo Delgado, a native of Torreon, Mexico, who never learned to speak English, but who instilled in Flores the desire to learn as much as possible.

Flores passed time during the war by volunteering at a local clinic and assisting teachers by grading papers. She also listened to Spanish- and English-language radio, the programming on which included music and comedy routines, among other shows.

In the El Paso neighborhood where Flores lived, everyone spoke Spanish. This was nothing out of the ordinary for Flores, who, along with her mother, spent a couple of years of her childhood in Juarez, Mexico, during the Repatriations of the 1930s, when between 1 and 2 million Mexicans and Mexican Americans were repatriated, or deported, to Mexico during the depths of the Great Depression. Critics both then and today charge Mexicans were “scapegoats” used to distract Americans from the problems of the Depression.

Flores recalls continued racial tension between Anglos and Mexicans Americans during the 1940s. For example, when she and her friends would go skate at a park, the group that was already there would move to another location when they saw her group coming, she says. She even recalls crushed cans being hurled her way in one instance.

Flores says she didn’t let this behavior bother her, however, as her mother encouraged her to be confident and befriend people. She obliged by making friends who’d at first intimidated her, she says.

Her husband faced similar situations, but reacted differently. In a 2002 interview, Ramón said a few soldiers disapproved of him and other Latino soldiers speaking Spanish – and that they almost reached the point of violence.

“If I hear you talking in Spanish, I would think it's Japanese and shoot you,” a non-Spanish speaking soldier said.

"I told him, ‘If I hear you talking in English, I would think it's German and shoot you too,’" Ramón recalled.

Flores says not knowing Ramón’s condition or location was difficult. But not being aware of when or if her husband would come home and be able to see his infant son for the first time was especially hard.

“It was a very sad period, even if I had my child – you’re happy when you have your children and enjoy them, but still their father’s not there, so it was kind of lonely and sad, looking forward to him coming back,” she said. “You know, I was never pessimistic about not seeing him again.”

Flores received letters twice a month from Ramón, but never detailing where he was or where he’d been. The letters were censored, Flores determined, because parts of sentences were marked out. Locations were particularly scratched out, she says.

Flores recalls relying heavily on a support system that consisted largely of family. Four of her husband’s brothers also served in World War II: Espiridion was stationed in Europe, Alberto and José were in the Philippines and Jesús, the eldest, was stateside in Arizona, according to information provided by Ramón during his interview.

“We helped each other [get through these difficult times],” said Flores, referring to her husband’s family and their friends.

Unable to find an apartment together, Ramón and Olga lived with Ramon’s parents, Leonila Contreras Flores and Jesus Flores. Flores continued to live with her in-laws for two months after Ramón was deployed in 1944. When her own mother became ill, Flores moved back in with her, only a couple of blocks away.

One day in 1946, while cleaning the house, Flores recalls sensing something behind her. She turned around and there he was, Ramón, watching her through the window. She was in complete shock because he never told her when he was coming back.

“It was such a wonderful day,” she said.

Life began to change for the couple: Ramón and Olga matured and grew together; both were still young, but what they had gone through forced them to grow up fast. Ramón resumed work as a baker at Kahn’s Bakery, but then got a higher-paying job at a local hospital.

He was different now: older, taller and more robust. His mannerisms had evolved as well, from being boyish to manly. He was now a man who’d get up in the middle of the night to walk around the house out of suspicion, Olga says. Also, he’d lost some of his hearing from an explosion, which he preferred not to talk about.

The couple ultimately had two sons and four daughters: Ramón, Elena, Ruth, Elvia, Sandra and David. Ramón and Elena both served in the Navy.

Flores says the family has held onto distinct Mexican traditions, such as making tortillas and cooking typical dishes like chicken with molé.

“We’re taken more serious now," said Flores of the progress Mexican Americans have made over the years, especially the progress of her children. "Because of their parents, they have more confidence. They feel like they can do stuff.”

Mrs. Flores was interviewed in El Paso, Texas, on September 1, 2007, by Edna Amador.