By Jonathan Damrich

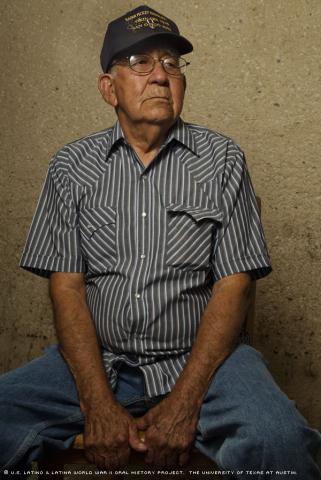

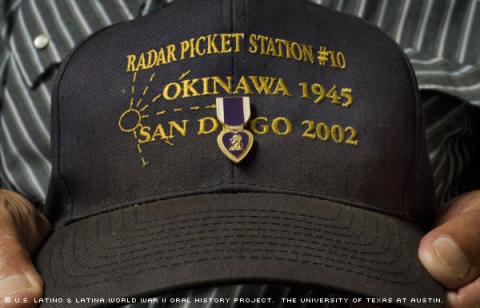

Odilon De Leon wore his Purple Heart in the middle of his cap, right below the spot where it read “Okinawa 1945.”

“I’m proud and happy that I served my country,” De Leon said, “even though I was disabled at the ripe old age of 17.”

The World War II veteran was badly burned May 3, 1945, when a Japanese plane flew into the port side of his ship, the USS LSMR-195, approximately 100 miles away from Okinawa.

The ship was carrying about 465 rockets, he said, which combined with the gasoline in the plane to create a “hellacious explosion.”

Ships of every size, infantrymen throwing up while waiting to storm the beach, and Japanese planes flying into the vessels filled the Okinawa seascape that evening, De Leon recalled.

It appeared at first that the LSMR-195 was going to escape with its crew of 80 intact, said De Leon, as all they had to do was go to the Philippines for supplies and then head back to the United States. But, while navigating in minefields, the kamikaze suddenly struck. The concussive impact was so great, De Leon said, it threw his shoes off.

Then the most traumatic part of the experience: Seamen began throwing the injured overboard, something that isn’t supposed to begin until the captain orders the ship abandoned, which, De Leon recalled, did eventually happen.

De Leon remembered surviving the incident by huddling with other men in a circle in the water, and using a flashlight to signal a ship to come pick them up, which occurred, he said, at some point before dawn. Eventually, he was put on the USS Solace, a medical ship ferrying soldiers to and from hospitals.

“I think my captain died of a broken heart,” said De Leon, describing how the leader was never able to get over the loss of the LSMR-195 and his men.

Years later, De Leon said he came into possession of a book consisting of letters the captain had written to the families of men who were lost on the LSMR-195. De Leon said he himself had planned to visit a friend who died on the vessel that day.

“Then it was, ‘Why him and not me?’” he said.

*****

Less than a year earlier, De Leon had made the decision to enlist, on Sept. 22, 1944, in San Antonio. He had lived there and worked in an automotive parts warehouse for a few years before coming of age.

De Leon was born in Von Ormy, Texas, a small town 30 minutes south of San Antonio on Interstate 35. His parents, Genaro or “Henry,” and Helena, or “Helen,” moved there after Henry completed his own military service in World War I.

“They were sharecroppers, just like everybody else,” De Leon said. “My mother and my father, I have to give them credit: They did take care of us as much as they possibly could.”

They had a lot to take responsibility for, as the De Leon family included 14 children. The family had a large garden, where it grew cotton, corn and other vegetables in order to be self-sufficient. War propaganda of the day referred to this as a “victory garden,” with the idea being that the self-sufficiency of families would allow more mass-produced supplies to go to soldiers, thereby contributing to the hoped-for victory.

De Leon, however, said his family’s plot was not a victory garden, but a means of survival.

“You couldn’t kill a chicken ‘cause then you wouldn’t have any eggs, so you killed a rooster. But 10 people eatin’ off one chicken doesn’t leave much,” said De Leon, adding that his mother would begin cooking at 4 p.m.

De Leon spoke highly of his father, who was also a Purple Heart recipient, for wounds received in France. He said the elder De Leon, being patriotic as a result of his own wartime service, had pushed him toward the military.

“A lot of people say they promised a lot of things,” said De Leon of the Armed Forces, “but I figured that I was fighting for our freedom and for the red, white and blue.”

That sentiment apparently stuck with him throughout the years. When the United States invaded Iraq, for example, De Leon was battling prostate cancer. But he said he and others in the hospital wanted to load up their oxygen tanks and wheelchairs and go fight anyway.

*****

De Leon said he could not envision himself going to college after returning from war, since he would have had to finish high school first. And the military did not explain anything to veterans about their benefits, he said, including the GI Bill.

“We were trained to kill, but they didn’t debrief us, they just handed me a paper and said, ‘Go home,’” De Leon said.

“We were grown men by the time we were 18, 19, and had been through so much in life, so much pain. All of this was stacking up on you, and a lot of us started drinking. . . . Combat fatigue was an excuse to be drinking. I didn’t give a hoot about nothing else.”

De Leon never got married. He said he never felt he could take care of a family after the stress WWII had put on him.

“I have no regrets,” De Leon said. “Life maybe could have been better, but you sure can’t go back and try to erase the things that happened there. I never will get well, and the war will never end for me. It’s up here,” he said, pointing to his head.

“Freedom don’t come cheap. Somebody has to pay for it, and I know that I paid for mine,” De Leon said. “I, and a million others, spilled our blood for the red, white and blue.”

Mr. De Leon was interviewed in Austin, Texas, on June 8, 2009, by Raquel C. Garza.