By Claudia Farias

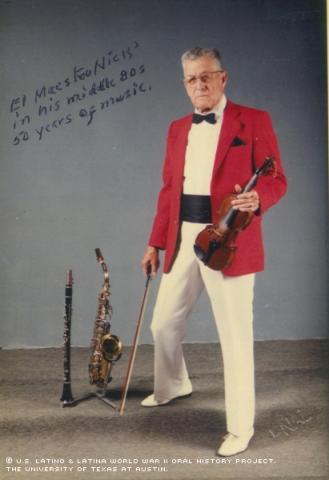

Nicanor Aguilar is something of a renaissance man, both as a musician and, at an age when most people would be slowing down, an athlete.

But Aguilar’s proudest accomplishment involves his efforts to end discrimination in his West Texas hometown after returning from the war.

Born Jan. 10, 1917, in Grand Falls in rural Texas, he spent most of his time helping his father, a tenant cotton farmer. The family of three brothers and two sisters helped pick cotton on 100 acres of land.

In 1930, a schoolhouse was finally built for Mexican American children next to a group of mesquite trees, but he left after one year to work with his father. No schools existed for Mexican American children after elementary; entry into the "Anglo" schools was banned. Aguilar learned most of his English from the Anglo children with whom he played in town.

One of his younger sisters, Maria, was prevented from attending junior high. But then along came Laura Francis Murphy, a teacher who was an advocate for teaching disenfranchised Latino students.

"[Ms. Murphy] did a lot for the Mexicans," Aguilar said.

His sister, Maria, ultimately became the first Hispanic to attend Grand Falls High School in 1942, thanks largely to Ms. Murphy.

Maria, an accomplished trumpet player with the family's orchestra, also won band competitions.

The entire Aguilar family was musically inclined. In 1927, at age 10, Aguilar began playing with his father and, later, his brothers.

"We were bad, but we played good music," Aguilar said, referring to his family's Grand Falls Orchestra ensemble.

The Aguilars played both Mexican and "American" music, including classics such as "Stardust." Each family member was paid $1 an hour to perform at weddings and other dances.

Aguilar started playing drums, but didn't like it because he would have to read the music simultaneously and miss watching the people dancing on the dance floor. So his father put him on the violin instead, and he was able to focus on his dual interests.

"I didn't like the violin too well, but there I was. At least I could see the people," he said, laughing. He would go on to play the clarinet, saxophone and piano for the next 50 years.

Aguilar proudly displayed a framed article from a 1946 edition of a regional newspaper headlined, "Aguilar's Brought 'Big Band Sound' To West Texas," and featuring a photo of the family playing.

This family bond helped inspire him to join the U.S. Army; younger brother Isabino Aguilar, had already enlisted. Aguilar received basic training at Camp Hood, Texas, and later Fort Ord, Calif. He was intent on fighting in Europe for his country and joining his kid brother in Germany. Aguilar ultimately shipped out to Italy and fought with the 36th Infantry Division on the European front.

Like many veterans, Aguilar is reticent in recalling war stories. In his interview, he focuses instead on the social battles he fought stateside. After the war, he found discrimination hadn’t disappeared in his hometown.

"There was the same discrimination in Grand Falls, if not worse," Aguilar recalled. "First, we'd work for a dollar a day. After the war, they raised it to $2 [for] 10 hours. And the whites would get $18 (a day) in the petroleum [field]."

Virtually none of the town's petroleum jobs were available to Latinos. Aguilar managed to maintain employment for one year with a small petroleum company, but only through a friend's assistance.

He felt he had to act to end his town's discriminatory climate.

"It wasn't right," he said. "I started calling other veterans and I told them, 'We have to do something good.'" Toward that end, they secured assistance from a League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) associate.

"We would investigate. For example . . . I would see [signs that read] 'No Mexicans, whites only.' There was only one [restaurant] that would serve us. We would write reports so they could give us the reasons. Some would answer us well; others, not so well. I brought those reports to El Paso and gave them to a LULAC associate. I don't know what he did with them after that. Once, a more powerful LULAC associate came to see me from San Antonio and congratulated me."

Gradually, the oppressive signs began coming down from diner windows.

In 1948, Aguilar moved to El Paso after a drought in Grand Falls, still continuing his work for LULAC. Today, he’s a LULAC Member At Large. He married Mercedes Borunda and the couple had four sons: Nick Jr., Pete, Paul and Joe.

Aguilar knows it was the efforts of many people like him that led to changes.

"You don't know the sacrifices we made," he said.

In addition to his civil rights efforts, Aguilar started competing in the Senior Olympics when he was 65, participating in running, bicycling and other events.

Today, he displays his mounted awards. In later correspondence, Aguilar noted that, all told, he has 67 awards, most of them gold or first place. And he added that 14 of those were earned at the age of 85.

In further post-interview correspondence, Aguilar writes extensively about the discrimination of his youth, seemingly as vivid a memory as the war. Perhaps he’d internalized much of that personal history earlier, preferring instead to record his thoughts at a more leisurely pace that would accommodate intermittent waves of emotion upon remembrance.

In the makeshift building -- the one next to the mesquite trees - he soaked up whatever learning he could, he wrote.

"We had scraps of education in old abandoned houses with teachers perhaps not qualified," he said. "I was kept three years in the seventh grade because the state could not afford any more books. I had one choice: Stay 'til I grew a beard or quit ..."

But he didn’t quit. And today his story of growing resonates powerfully and speaks volumes.

Mr. Aguilar was interviewed in El Paso, Texas, on December 29, 2001, by Maggie Rivas Rodriguez.