By Christine Powers

"I had a bitter taste in my mouth when I learned both my sons were drafted for Vietnam," said World War II veteran Mike Gomez.

He leaned forward in his seat, paused for a second and then emphasized: "A bitter taste."

Frustrated at the possibility of losing his children and recalling his memories of the European Theater, Gomez, 78, says the draft seemed to be an unavoidable family tradition.

At one point, when he complained to U.S. Sen. Barry Goldwater that both sons were serving, Goldwater arranged for one son to be sent home: Gomez and his wife only had to decide which one it would be. The parents couldn't make such a decision, however, so they left both sons in Vietnam. Both returned safely.

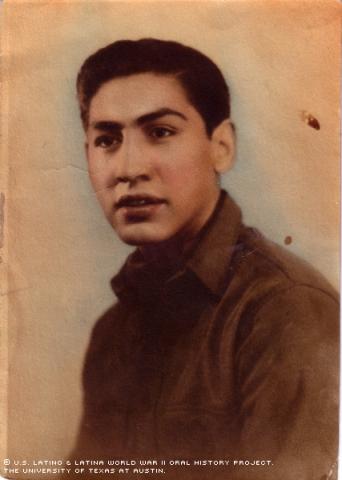

The U.S. government drafted Gomez and both of his brothers for WWII 60 years ago. Gomez, who served in the 837th Ordinance Combat Depot Company in Gen. George S. Patton's 3rd Army, was at D-Day Plus Two, June 8, 1944.

By the time he was drafted, in May of 1943, Gomez was already married and working as a stock boy in a Phoenix, Ariz., clothing store, and had a baby on the way. Shortly after high school, he’d married his high school sweetheart, Dora Mendoza, a fast-pitch softball player who caught his eye at a street dance in the park.

Gomez says he knew what to expect at boot camp because in high school he’d been in ROTC, in which he enrolled "so my parents need not buy me clothes," he said. There were 11 people in the family, including Gomez's six sisters and two brothers. During and after the Great Depression, all nine children worked to help put food on the table.

After training in California, Washington and New Jersey, Gomez was sent to Normandy, France, to fight in the largest amphibious invasion in history, D-Day.

U.S. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower commanded the Allies in "Operation Overlord" on the five beaches in the Normandy area, codenamed Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno and Sword.

On June 8, 1944, on one of the hundreds of Allied ships that approached Omaha Beach during the third day of the Normandy invasion, 19-year-old Gomez knew what was coming.

As he prayed aloud, he put on the tarp-like cover to protect him as he made his way to shore. After climbing down the ship's ropes, the platoon made their way to the shore in a landing craft. They saw thousands of dead bodies floating in the water and, even on the third day, the shooting was heavy.

"We ran like hell when we got to the beaches," Gomez said. "It's a matter of survival, but you always have a little fear in you. It's their life or yours."

Gomez adds the government had a reason for drafting young men.

"The United States drafted 18- and 19-year-olds because younger men do not feel fear to the depth that men in their mid-20's do," he said. "Younger men feel invincible, and the seriousness of the situation does not completely register with the young soldiers."

However, Gomez says there were signs of some fear: heavy smoking and serious praying just before their journey to shore.

As Germans fired their machine guns on the beach, the soldiers jumped into shell holes in the sand to protect themselves.

When he jumped into one particular shell hole on the beaches, Gomez says he discovered a childhood friend from his neighborhood, Frank Calles. The two soldiers from different units took a moment amid the chaos to say hello and comment on the extraordinary encounter. They then separated and only reunited in Phoenix years later.

In the months ahead, Gomez and his unit, under Gen. Patton's command, were responsible for delivering supplies to the front line, using tanks as cover from German fire.

Some of his most vivid memories include the men who "lost their mind," panicked over a false alarm of a gas attack, and forced to transfer out; waking up in a graveyard with open graves; seeing a fellow soldier whose throat had been slit while he was standing watch; watching the "elated" though malnourished American and British POWs freed; seeing hundreds of bodies piled high at the concentration camp at Dachau, the saddest sight he says he has ever seen.

The trip to the camp was intended to make a point, Gomez says.

"They wanted us to travel through the concentration camp, possibly to make us realize why we were fighting," he said.

The Nazi failure to successfully defend the Normandy beaches from the Allied liberation forces marked the beginning of the end for Adolf Hitler's Germany. The invasion of Normandy took years to plan and is the most successful amphibious operation in the history of war.

"I'm glad I had that experience,'' Gomez said. "No money can buy it. But I would never want to go through that again . . . never."

Gomez literally tasted victory when his unit "confiscated" champagne from a German chateau, filling a truck bed to the brim with the victory juice.

Less than 50 miles from Berlin, when the Germans surrendered, the soldiers partied in the streets on the "jubilant day," Gomez said.

Likewise, on the August day his outfit learned the Japanese had surrendered and the war was finally over, Gomez recalled, "we drank whatever we could get our hands on." The French farmhouses always graciously supplied the U.S. soldiers with wine, he explained.

Gomez returned home uninjured and was honorably discharged on Nov. 21, 1945, having earned the rank of Technician Fifth Grade.

He returned home by train. When he arrived, his wife barely recognized him as she paced back and forth trying to figure out which soldier was her husband.

"I had to point to myself and say, 'It's me, it's me!'" recalled Gomez with a chuckle.

Gomez also reunited with his son Michael, whom Gomez hadn’t seen since shortly after the boy's birth.

Gomez worked as a bartender while putting himself through school. With the help of the GI Bill, he attended Arizona State Teachers College, now Arizona State University, and earned a degree in accounting in 1951.

Having never left his home state after being discharged from military service, he eventually retired from the workforce as the chief real estate negotiator for the Arizona Bureau of Reclamation, which builds dams and aqueducts.

Now married 60 years, Gomez proudly boasts he "would marry her all over again" if he had the chance.

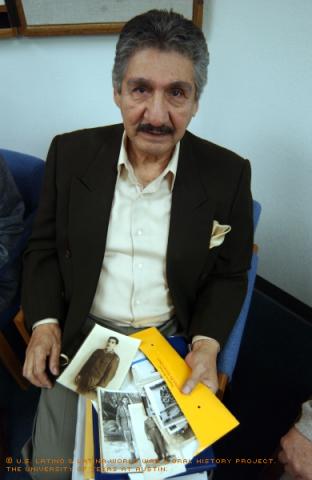

Mr. Gomez was interviewed in Phoenix, Arizona, on January 4, 2003, by Ricardo Pimentel.